CAIRO (AP) — Around midnight in mid-November, Libyan militiamen in two Toyota pickup trucks arrived at a residential building in a neighborhood of the capital of Tripoli. They stormed the house, bringing out a blindfolded man in his 70s.

Their target was former Libyan intelligence agent Abu Agila Mohammad Mas’ud Kheir Al-Marimi, wanted by the United States for allegedly making the bomb that brought down New York-bound Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, just days before Christmas in 1988. The attack killed 259 people in the air and 11 on the ground.

Weeks after that night raid in Tripoli, the U.S. announced Mas’ud was in its custody, to the surprise of many in Libya, which has been split between two rival governments, each backed by an array of militias and foreign powers.

Analysts said the Tripoli-based government responsible for handing over Mas’ud was likely seeking U.S. goodwill and favor amid the power struggles in Libya.

Four Libyan security and government officials with direct knowledge of the operation recounted the journey that ended with Mas’ud in Washington.

The officials said it started with him being taken from his home in the Abu Salim neighborhood of Tripoli. He was transferred to the coastal city of Misrata and eventually handed over to American agents who flew him out of the country, they said.

The officials spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals. Several said the United States had been exerting pressure for months to see Mas’ud handed over.

“Every time they communicated, Abu Agila was on the agenda,” one official said.

In Libya, many questioned the legality of how he was picked up, just months after his release from a Libyan prison, and sent to the U.S. Libya and the U.S. don’t have a standing agreement on extradition, so there was no obligation to hand Mas’ud over.

The White House and Justice Department declined to comment on the new details about Mas’ud’s handover. U.S. officials have said privately that in their view, it played out as a by-the-book extradition through an ordinary court process.

A State Department official, speaking on condition of anonymity in line with briefing regulations, said Saturday that Mas’ud’s transfer was lawful and described it as a culmination of years of cooperation with Libyan authorities.

Libya’s chief prosecutor has opened an investigation following a complaint from Mas’ud’s family. But for nearly a week after the U.S. announcement, the Tripoli government was silent, while rumors swirled for weeks that Mas’ud had been abducted and sold by militiamen.

After public outcry in Libya, the country’s Tripoli-based prime minister, Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, acknowledged on Thursday that his government had handed Mas’ud over. In the same speech, he also said that Interpol had issued a warrant for Mas’ud’s arrest. A spokesman for Dbeibah’s government did not answer calls and messages seeking additional comment.

On December 12, the U.S. Department of Justice said that it had requested that Interpol issue a warrant for him.

After the fall and killing of longtime Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi in a 2011 uprising-turned-civil war, Mas’ud, an explosives expert for Libya’s intelligence service, was detained by a militia in western Libya. He served 10 years in prison in Tripoli for crimes related to his position during Gadhafi’s rule.

He was released in June after completing his sentence. After his release, he was under permanent surveillance and barely left his family home in the Abu Salim district, a military official said.

The neighborhood is controlled by the Stabilization Support Authority, an umbrella of militias led by warlord Abdel-Ghani al-Kikli, a close ally of Dbeibah. Al-Kikli has been accused by Amnesty International of involvement in war crimes and other serious rights violations over the past decade.

After Mas’ud’s release from prison, the Biden administration intensified extradition demands, Libyan officials said.

At first, the Dbeibah government, one of the two rival administrations claiming to govern Libya, was reluctant, citing concerns of political and legal repercussions, said an official at the prime minister’s office.

The official said U.S. officials continued to raise the issue with the Tripoli-based government and with warlords they were dealing with in the fight against Islamic militants in Libya. With pressure mounting, the prime minister and his aides decided in October to hand over Mas’ud to American authorities, the official said.

Dbeibah’s mandate remains highly contested after planned elections failed to happen last year.

“It fits into a broader campaign being conducted by Dbeibah, which basically consists of giving gifts to influential states,” said Jalel Harchaoui, a Libya expert and an associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute. He said Dbeibah needs to curry favor to help him remain in power.

More than a decade after the death of Gadhafi, Libya remains chaotic and lawless, with militias still holding sway over large territories. The country’s security forces are weak, compared to local militias, with which the Dbeibah government is allied to varying degrees. To carry out the arrest of Mas’ud, the Dbeibah government called on al-Kikli, who also holds a formal position in the government.

The prime minister discussed the Mas’ud case in a meeting in early November with al-Kikli, according to an employee of the Stabilization Support Authority who had been briefed on the matter. After the meeting, Dbeibah informed U.S. officials of his decision, agreeing that the handover would take place within weeks in Misrata, where his family is influential, a government official said.

Then came the raid in mid-November, which was described by the officials.

Militiamen rushed into Mas’ud’s bedroom and seized him, transporting him blindfolded to a detention center run by the SSA in Tripoli. He was there for two weeks before he was given to another militia in Misrata, known as the Joint Force, which reports directly to Dbeibah. It’s a new paramilitary unit established as part of a network of militias that support him.

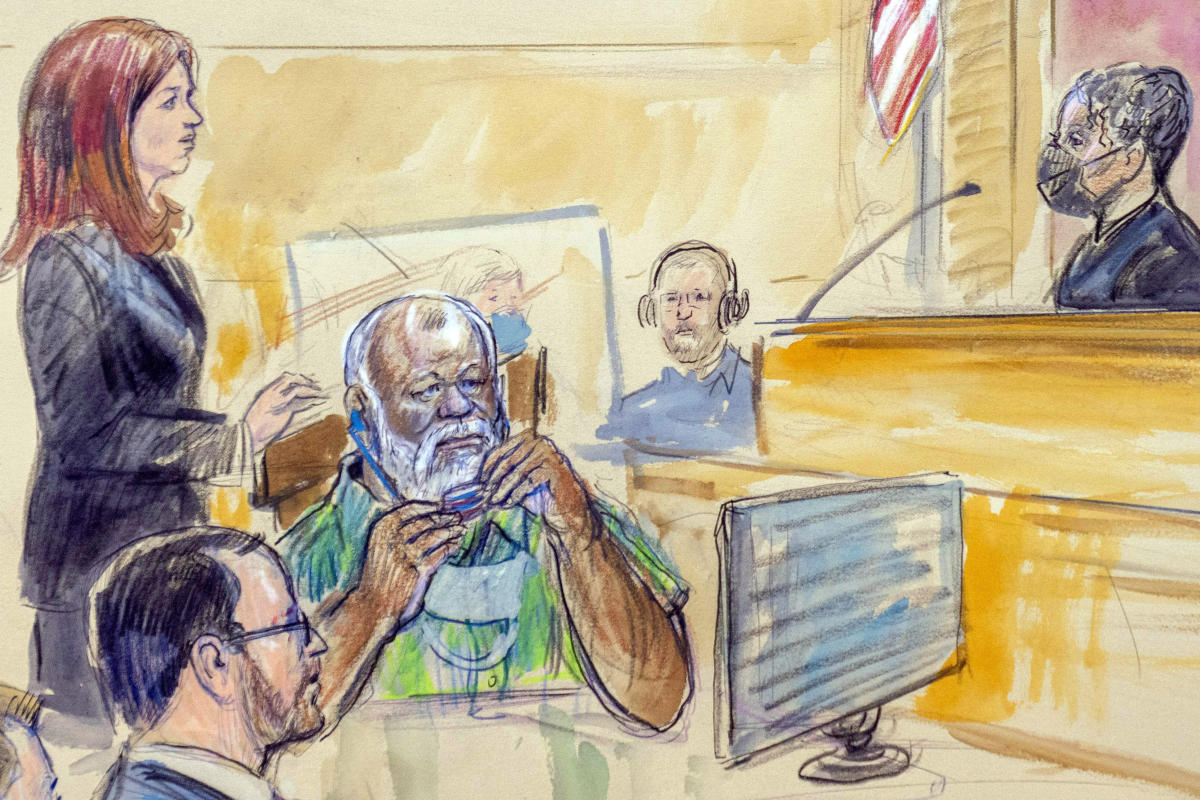

In Misrata, Mas’ud was interrogated by Libyan officers in the presence of U.S. intelligence officers, said a Libyan official briefed on the interrogation. Mas’ud declined to answer questions about his alleged role in the Lockerbie attack, including the contents of an interview that the U.S. says he gave to Libyan authorities in 2012 during which he admitted to being the bomb-maker. He insisted his detention and extradition are illegal, the official said.

In 2017, U.S. officials received a copy of the 2012 interview in which they said Mas’ud admitted building the bomb and working with two other conspirators to carry out the attack on the Pan Am plane. According to an FBI affidavit filed in the case, Mas’ud said that the operation was ordered by Libyan intelligence and that Gadhafi thanked him and other members of the team afterwards.

Some have questioned the legality of Mas’ud’s handover, given the role of informal armed groups and a lack of official extradition procedures.

Harchaoui, the analyst, said Mas’ud’s extradition signals the U.S. is condoning what he portrayed as lawless behavior.

“What the foreign states are doing is that they are saying we don’t care how the sausage is made,” he said. “We are getting things that we like.”

___

Associated Press writer Ellen Knickmeyer in Washington contributed to this report.