The portrait artist Barkley L. Hendricks, who died in 2017, considered the Frick Collection one of his favorite museums. Now Hendricks’s celebratory, large-scale paintings of Black Americans will hang in that institution, long the home of Rembrandt, Bronzino and Van Dyck, as the first artist of color to have a solo show at the 87-year-old Frick.

In the fall of 2023, the museum will intersperse about a dozen of Hendricks’s portraits among its own holdings in an exhibition at its temporary home, Frick Madison. Hendricks made life-size portraits of Black friends, relatives and strangers he encountered on the street — paintings that only recently have been widely recognized by museums and the art market but helped set an assertive tone for figuration and opened the field for many younger artists.

“He was painting in the old master tradition — the quality is great, their visual impact is there,” said Aimee Ng, a curator at the Frick. “We wanted to foreground his paintings as we would treat any historical artist.”

Ng is organizing the show with Antwaun Sargent, a director at Gagosian, who will serve as a consulting curator and initially proposed the idea.

“You have a painter who is very much in the tradition of the old masters, and who was largely not revered during his time,” Sargent said. “He was thinking about contemporary culture, but he was also thinking deeply about our history, about artists like Whistler.”

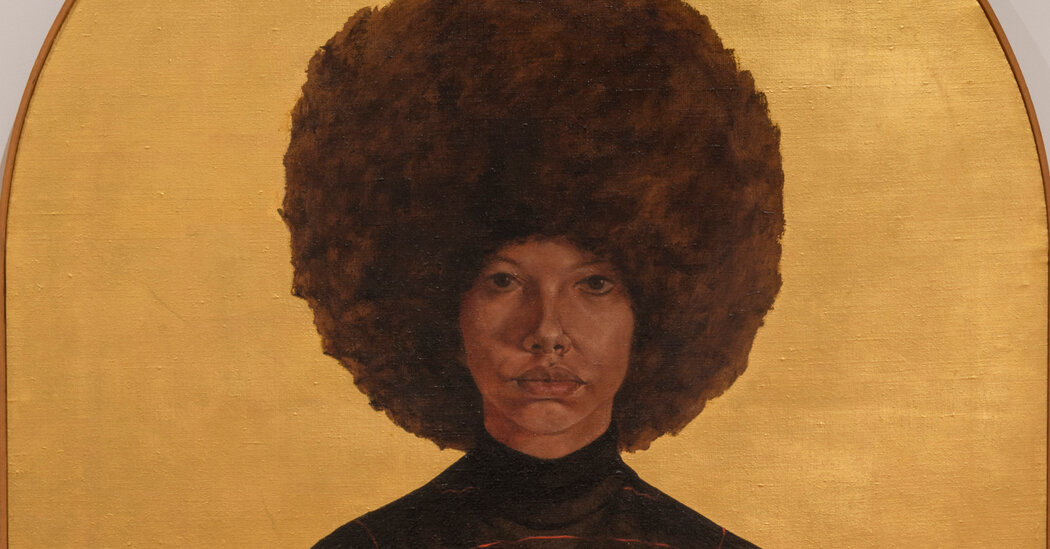

Hendricks’s portraits of Black men and women will hang throughout the museum. A canvas of his cousin in an Afro, “Lawdy Mama” (1969), for example, employs the gold leafing technique used in religious depictions, and is exemplified by a group of early Italian Renaissance panels in the Frick’s collection.

The curators pointed to his limited-palette painting “Steve” (1976), noting it evokes Northern Renaissance artists like Jan van Eyck, whose “The Virgin and Child with St. Barbara, St. Elizabeth, and Jan Vos” resides in Frick Madison’s Northern European galleries.

“We’re not cornering him off — we’re putting the work in the collection and saying, he is as significant as anything else on any other wall in the museum,” Sargent said. “I’m interested in what the reaction will be and what connection any of our visitors are going to make between Barkley’s work and the work of these European old masters.”

A catalog exploring Hendricks’s impact will include contributions by artists such as Derrick Adams, Nick Cave and Toyin Ojih Odutola, acknowledging Hendricks’s widespread influence.

“For the generation of portrait painters that came after him — Kehinde Wiley, Amy Sherald, even Rashid Johnson — he was an important predecessor,” Sargent said. “I would even argue that, without Barkley’s work, you don’t get this moment in figuration that you’re seeing today.”

Hendricks’s interest in Black figuration in the 1960s and 1970s put him outside the mainstream of Black artists during that period, many largely preoccupied with civil rights and the Black Power movement.

His work was largely unacknowledged until recently, when the art world has begun to correct the canon, and when Black portraiture has become popular.

Though the moment seems overdue for the Frick to focus on a contemporary Black artist, the museum — whose mandate is to collect and present European art from the 14th century to the 19th century — acknowledges that there will inevitably be some pushback from purists.

The Frick has tentatively been experimenting with more progressive programming. Its current project, “Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters,” features the work of four artists — Doron Langberg, Salman Toor, Jenna Gribbon, and Toyin Ojih Odutola — exploring issues of gender and queer identity that have typically been excluded from narratives of early modern European art.

“There are traditionalists who don’t think there is a place for artists of color because that is not what the Frick has been traditionally doing, and there are those who are really dying for this kind of thing,” Ng said. “Our young fellows group is bigger than it has ever been. That tells me we are going in the right direction. I don’t want to alienate people who have been with the Frick for 40, 50, 60 years. I do want to bridge the historic collection and other art.”