“Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars” offers glimpses of a life in rock ’n’ roll — from doo-wop to “Metal Machine Music” — and tracks the evolution of one of music’s polarizing legends.

At a glance, it is a modest artifact: a five-inch reel of audio tape, housed in a plain cardboard box. Its wrapping bears a postmark of May 11, 1965, and the sender and addressee are the same: Lewis Reed.

But if there is a “Rosebud” in Lou Reed’s archive — a telltale totem from youth — this is it. The box, still unopened, was found in Reed’s office after his death in 2013. It was only after the New York Public Library acquired his materials four years later from Reed’s wife, the artist Laurie Anderson, that archivists finally opened it and played the tape. What they found were some of the earliest known recordings of songs that Reed wrote for the Velvet Underground, his groundbreaking 1960s band, in stripped-down, almost folky acoustic versions that may leave fans and scholars stunned.

The tape is at the center of “Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars,” the first exhibition drawn from Reed’s archive, which will open on Thursday at the Library for the Performing Arts, at Lincoln Center.

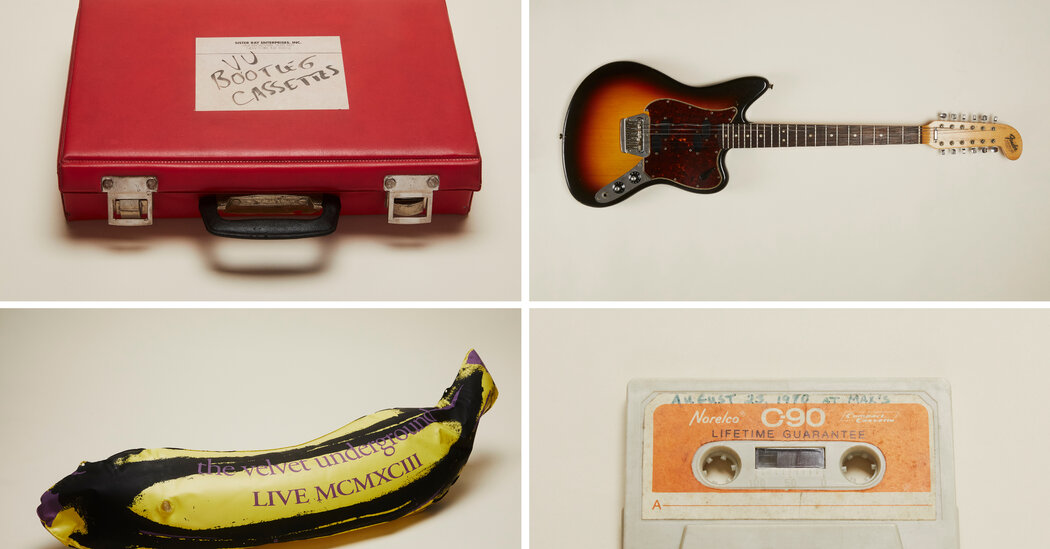

The full archive is enormous, with about 600 hours of audio, along with videos, correspondence, legal paperwork and forms of documentation that range from photos of a White House visit in 1998 to endless petty-cash receipts from life on the road in the 1970s. There are tour rehearsals, audio experiments, handwritten lyrics, stacks of Velvet Underground bootlegs and even Coney Island Mermaid Parade banners from 2010, when Reed and Anderson served as king and queen.

To Anderson’s delight, it is available for exploration by anyone with a library card, although, as she notes, the full character of Reed himself — irascible, sentimental, obsessed with sound and tech — can’t be conveyed from his scraps.

“This collection is to inspire people,” Anderson said in an interview at her TriBeCa studio, where a portrait of Reed performing in dark shades looms on a wall. “It’s not necessarily to say, ‘Here’s the real Lou Reed.’ That’s never what it was meant to be. Here’s a lot of his music and how he did it. Be inspired by it. But it’s not and can’t be a real picture of the man.”

Anderson said she had originally intended to give the archive to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, home to the papers of literary giants like James Joyce, Norman Mailer and Don DeLillo. But she changed her mind in 2015 after a law was passed in Texas allowing people to carry handguns on college campuses.

“I called them up,” she recalled. “‘This thing we’ve been talking about for a couple years? It’s off. Because of guns.’”

A few months later, Anderson read an article in The New York Times about a program at the New York Public Library to digitize archives, and began discussions there.

The exhibition, which runs until March 4, 2023, has a sampling of items from Reed’s complete archive, which takes up 112 linear feet of shelf space and has 2.5 terabytes of digital files, making it one of the library’s largest audiovisual collections. The show was curated by Don Fleming, a music producer and archivist, and Jason Stern, who worked with Reed in the last few years of his life.

Visitors will first encounter a video of Reed calmly reciting the world-gone-to-hell lyrics of “Romeo Had Juliette,” from his 1989 album “New York” (“Manhattan’s sinking like a rock, into the filthy Hudson what a shock”), establishing Reed as poet, provocateur and chronicler of Manhattan’s demimondes. Further galleries showcase Reed’s time with the Velvet Underground, his solo work and his poetry, and a listening room will feature the meditation music Reed created as a practitioner of tai chi and an immersive version of “Metal Machine Music,” his notoriously abrasive 1975 album.

The artifacts offer glimpses of a life in rock ’n’ roll. A small box houses part of Reed’s collection of 45 r.p.m. records, with some of his teenage doo-wop and R&B favorites like the 5 Willows’ “Lay Your Head on My Shoulder” and Huey (Piano) Smith’s “Don’t You Just Know It,” along with Reed’s own high school rock band, the Jades. There are boxes of Velvet Underground recording tapes and receipts for purchases as mundane as coffee and as striking as a studded dog collar that is almost certainly the one Reed wore on the cover of his 1974 live album “Rock ’n’ Roll Animal” ($13.50 from Pleasure Chest on Seventh Avenue).

Most endearing is a set of holiday greeting cards from Moe Tucker, the Velvets’ drummer, which address Reed as “Honeybun”; the ones on display are just a sampling among the many held in the archive. The collection has none from Reed, but “every Valentine’s Day he’d send Moe a card,” Stern said.

For the show, Anderson also lent some of Reed’s guitars and tai chi weapons, which are not part of the library archive.

Except for Reed’s personal Rolodex, every item in the library collection is accessible to the public. Discoveries have already been made, like a previously unknown song, “Open Invitation,” that was found on a cassette from the mid-80s — a rock ’n’ roll tune about tai chi, the martial art that became Reed’s great passion late in life.

Just last month, Fleming and Stern realized they had misdated a tape labeled “Electric Rock Symphony,” assuming it was a 1970s demo for “Metal Machine Music.” After examining the tape further, and comparing its audio to that of others in the collection, they now believe it was made in 1966, or possibly 1965, a sign of how long the “Metal Machine” technique — feedback-driven guitar drones, adapted from the composer La Monte Young — had gestated.

The biggest discovery so far is the May 1965 tape. Reed had shown it to friends, though its contents were unknown even to the Velvets’ most determined bootleg hunters. Featuring Reed playing acoustic guitar and harmonizing with John Cale like coffeehouse folk performers, the tape’s versions of “I’m Waiting for the Man,” “Pale Blue Eyes” and “Heroin” are miles away from the explosive sound the two young men would develop just months later with the Velvet Underground.

On Aug. 26, the specialty reissue label Light in the Attic will inaugurate a series of Lou Reed archival albums with the release of “Words & Music, May 1965,” with 11 cuts from that tape, along with other early recordings. Among those early tracks is Reed softly singing the spiritual “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” in 1963 or 1964 with fingerpicked guitar accompaniment.

For Anderson, those tapes are a sign of the twisting path that Reed took to become an artist. “That’s a valuable thing for people to understand,” she said. “You don’t become Lou Reed overnight.”

Reed may have mailed the tape to himself as an attempt to establish copyright. But why he never opened it, and yet kept it so close to him — it was on a shelf filled with his own CDs — is a mystery.

“It’s amazing that he had this document from his very first songwriting with him the whole time,” Fleming said. “He just kept it there. He didn’t need to open it.”

The library exhibition includes a listening room where versions of “Metal Machine Music” will play, interspersed with the “Electric Rock Symphony” tape and a track from Reed’s ambient album “Hudson River Wind Meditations” (2007). “Metal Machine Music” will be heard in its original quadraphonic mix — for four speakers, rather than the two of a standard stereo recording — and listeners can experience an immersive live document from 2009 of Reed’s group Metal Machine Trio.

The story of the 2009 recording, made in the three-dimensional audio format known as ambisonic, shows Reed’s lifelong fascination with technology, as well as his mix of toughness and sensitivity.

In an interview, Raj Patel of Arup, the acoustic technology company that made the recording, recalled meeting Reed in 2008, and finding him intrigued but skeptical about the format. He eventually agreed to let Arup tape a performance in New York, with microphones placed around the venue and onstage, including just behind Reed’s head — to let listeners hear how the performance sounded from Reed’s own perspective.

A week later, Reed arrived at Arup’s studio, prepared for disappointment. After listening for about five minutes, Reed raised his hand to stop the music. Tears were welling in his eyes.

“That,” Patel recalled Reed saying, “is the best [expletive] live recording I’ve ever heard.”