HONG KONG — Chinese officials gathering this week for the country’s most important political event in years face an increasingly turbulent picture at home and abroad. But the theme of the event is continuity — of President Xi Jinping as leader, and with that the likelihood of friction with the U.S.-led West.

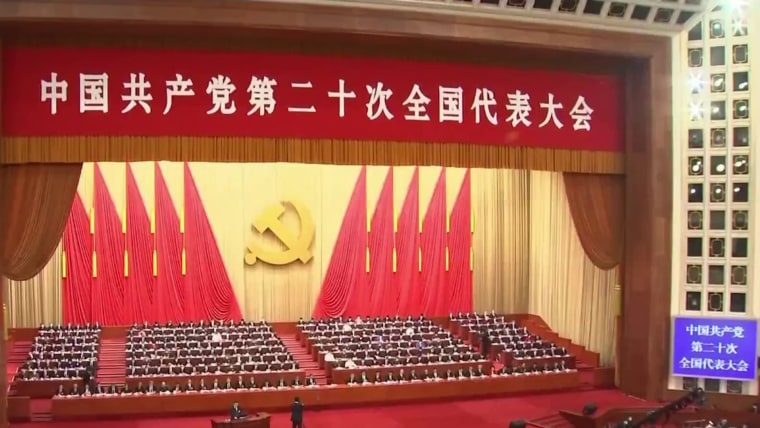

Xi, China’s most powerful leader in decades, is poised to secure an unprecedented third term at this week’s twice-a-decade National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing.

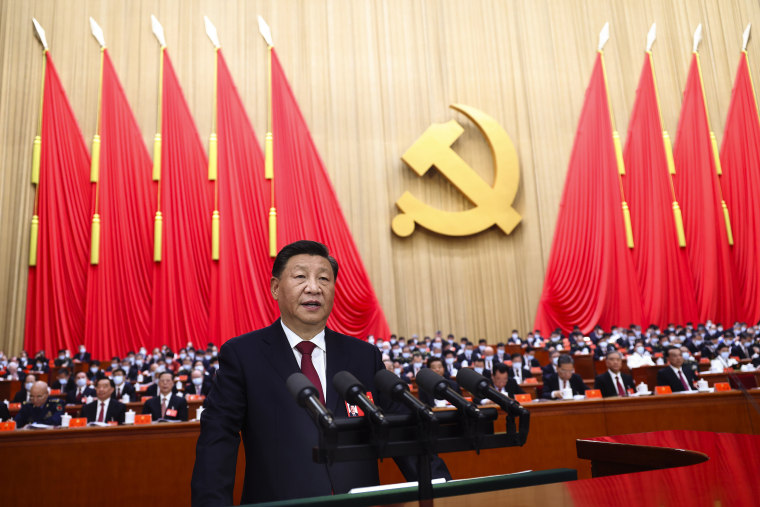

In a speech opening the congress on Sunday, Xi gave no indication that China — a country the United States and its allies consider their main global challenger — would change course on issues like Taiwan, Hong Kong and its strict “zero-Covid” policy. But he also foresaw challenges and vowed China would not shy away from competition or confrontation.

“We must strengthen our sense of hardship, adhere to the bottom-line thinking, be prepared for danger in times of peace, prepare for a rainy day, and be ready to withstand major tests of high winds and high waves,” Xi told an audience of about 2,300 delegates in the Great Hall of the People.

At the weeklong congress, Xi is expected to obtain a third five-year term as general secretary of the ruling Chinese Communist Party, as well as head of the country’s armed forces. (His third title, president of China, isn’t up for renewal until next spring.) He could even be named “party chairman,” a title previously bestowed only on Mao Zedong, who ruled the People’s Republic of China for 27 years after its founding in 1949.

The lack of surprises in Xi’s speech reflects his overall confidence, said Richard McGregor, senior fellow for East Asia at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, Australia.

“He’s confident in terms of his control over the party, control over the direction of policy,” he said. “Whether he’s confident over the economy and the impact of Covid-19, who knows.”

Xi faces a host of problems that will make his third term unlike his first two, not least an economic slowdown spurred by a property sector crisis and “zero-Covid” restrictions that officials say are necessary to protect the health care system from being overwhelmed. On the global stage, China’s relations with the United States, Europe and Australia are at their lowest point in years amid economic competition, tensions in the Taiwan Strait and differences over Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Rather than dwell on those issues, Xi’s speech emphasized matters of national security and his past successes.

“For the last 10 years under the leadership of President Xi, China has taken big strides forward,” Wang Huiyao, a former adviser on the State Council, China’s top administrative body, and the president of the country’s Center for China and Globalization think tank, said. “Those achievements have certainly strengthened the president’s leadership.”

Under Xi, China’s gross domestic product has more than doubled to $17.7 trillion. The number of people living in rural poverty fell from 82 million in 2013 to 6 million in 2019, according to World Bank data, while the number of mainland Chinese billionaires as measured by Forbes magazine grew from 113 in 2012 to 539 in 2022, compared with 735 in the United States. China has also vastly expanded its infrastructure, more than quadrupling its network of high-speed rail lines to about 25,000 miles — more than the rest of the world combined.

Alongside its progress at home China has increased its footprint abroad, working to project soft power and expand trade and other alliances while also making aggressive moves in the South China Sea, where it has territorial disputes with multiple countries. China’s annual defense budget has more than doubled to $230 billion as Xi accelerates the modernization of his military, increasing its number of aircraft carriers from one to three, compared with America’s 11. The country also has an ambitious space program, landing spacecraft on the moon and Mars in recent years and nearing completion on its own space station.

But Xi has also made China more authoritarian, consolidating power in his own hands, enhancing state surveillance and forcefully crushing dissent. He oversaw a campaign of abuses against Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in the western region of Xinjiang that the United States and others say amounts to genocide. Chinese officials deny these allegations, saying that they are fighting terrorism, and that large detention camps housing Uyghurs and other minorities are vocational and training centers.

In the Chinese territory of Hong Kong, critics say a national security law Beijing imposed in 2020 has eroded civil liberties, chilled expression and all but wiped out political opposition. The Chinese government says the national security law was necessary to restore order in Hong Kong after months of anti-government protests in 2019.

Xi has sidelined political rivals and sought to weave his views on Chinese socialism into everyday life, with “Xi Jinping Thought” taught starting in primary school and fervently studied by officials. Experts have expected Xi to remain in office ever since he did away with China’s traditional presidential two-term limit in 2018.

Yaqiu Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch, sees a third Xi term as a tragedy.

“It’s devastating, especially for someone who was born in the 1980s, because we grew up in a country that was becoming more prosperous and more liberalized,” said Wang, who was born and raised in China. “You felt things were getting better, people felt empowered and felt a sense of pride.”

Now “human rights have gotten dramatically worse — in every aspect,” she added.

The growing authoritarianism in China has global implications as Xi presents his governance model as an alternative to democracy.

“He wants to project this view of China being a force for stability, but it’s a force for stability that is different from the U.S. vision,” said Ja Ian Chong, an associate professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.

International flashpoints

One thing absent in Xi’s résumé is an era-defining achievement symbolizing his legacy, said Jinghan Zeng, professor of China and international studies at Lancaster University in England.

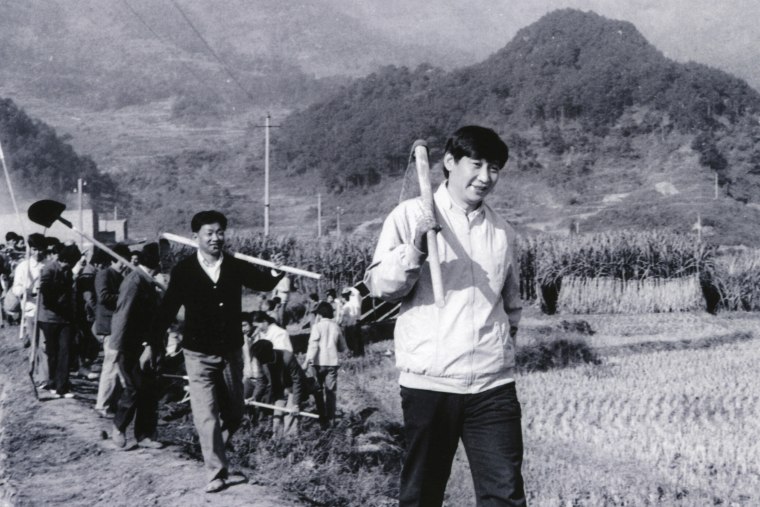

Deng Xiaoping, China’s paramount leader in the 1970s and ’80s, championed overhauling and opening up the country’s economy, while Mao founded the Communist state itself. For his part, Xi has made no secret of his desire to unite China with Taiwan, a self-governed island that Beijing claims as its territory.

“If Xi Jinping wants to be considered as a leader equivalent to Chairman Mao, how is he going to justify that?” Zeng said. “If you look around, you can’t really see anything” that would work — “except reunification with Taiwan.”

In his speech Sunday, Xi reiterated his opposition to Taiwan independence and criticized interference by “external forces.”

“We persist in striving for the prospect of peaceful reunification with the greatest sincerity,” he said. “However, there is no commitment to renounce the use of force and the option to take all necessary measures is retained.”

Taiwan, which has never been ruled by the Chinese Communist Party, responded by warning Beijing against “acts of coercion and aggression.”

“Only the 23 million people in Taiwan have the right to decide the future,” the Mainland Affairs Council said in a statement.

President Joe Biden has said that the U.S. would step in to protect Taiwan — a democracy and a major microchip manufacturer — in the event of an invasion, raising the prospect of a direct military conflict between Washington and Beijing. Though Xi has greatly increased pressure on Taiwan, few experts believe he will use significant force against the island in the next five years, according to a survey published last month by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank.

Another flashpoint in China’s international relations is Russia’s war in Ukraine, though Xi did not mention it directly in his speech. Beijing and Moscow have forged closer ties over the past year, and Xi has refrained from condemning Russia’s actions.

At 69, Xi is already past the age when Chinese officials customarily retire. The makeup of the new Politburo Standing Committee — China’s top governing body — could provide clues as to potential successors: anyone who walks out closely behind Xi and isn’t already too old. If no one fits that profile, it will be seen as a signal that Xi intends to stay in power indefinitely.

“Before Xi Jinping became president in 2012, there was a lot of wishful thinking in the West that he would become a pro-liberal leader,” Zeng said. “As then, now it would equally be a mistake to think that he will change course during his third term.”

According to Stephanie Carvin, an associate professor of international affairs at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario, Xi views China as a rising power and his worldview is shaped by great-power competition. That means tensions with the United States and many of its allies are unlikely to ease anytime soon.

“The long-term goals of President Xi, as well as general attitudes in the West, will make it very difficult for us to have more cooperation during his third term,” she said. “We’ve been on this path for close to a decade now.”