The United Nations on Tuesday officially declared that the global population had reached 8 billion, highlighting massive growth in the last few decades and the decades to come, but also raising concerns about food scarcity and prices around the world.

Every night around 828 million people go to bed hungry, according to the World Food Program (WFP), a United Nations organization focusing on providing food assistance globally.

Since 2019, the number of people facing significant food insecurity has increased from 135 million to 345 million, according to WFP.

“We are on the way to a raging food catastrophe,” U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres told world leaders at the G20 Summit in Bali, Indonesia, this week. “People in five separate places are facing famine.”

The global population has been growing slowly since the 1950s, falling under 1% in 2020.

The latest projections by the U.N. show the global population may reach 8.5 billion in 2030 and 9.7 billion in 2050. It is projected to peak at around 10.4 billion during the 2080s and remain at that level until 2100.

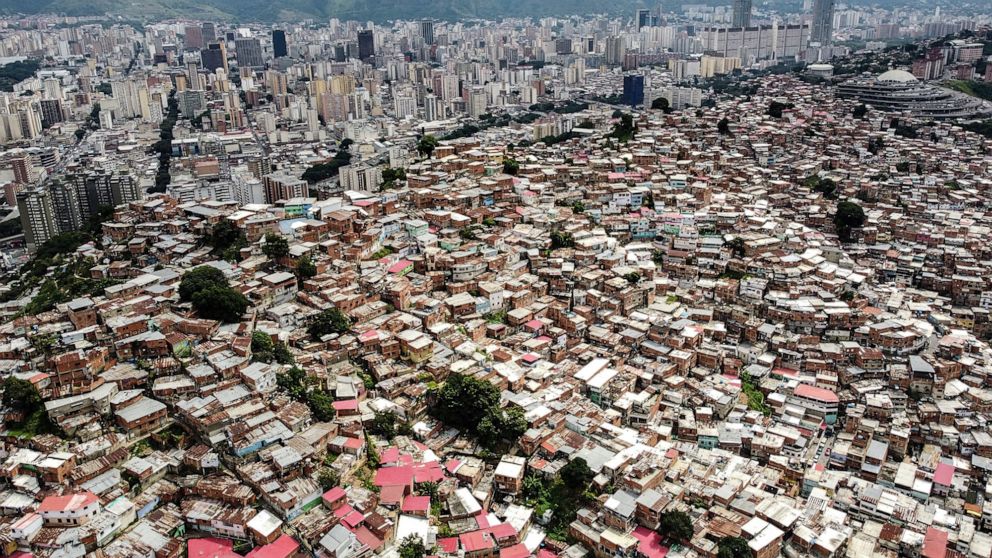

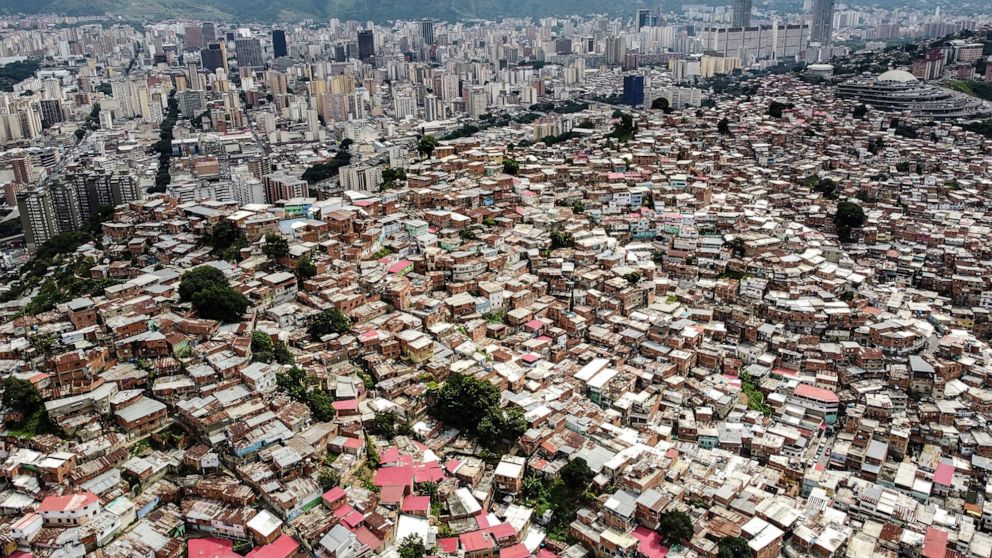

An aerial view shows overpopulated neighborhoods in the southwest of Caracas, Venezuela, Aug. 27., 2022.

Yuri Cortez/AFP via Getty Images, FILE

India will surpass China as the world’s most populous country next year, according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

The world produces enough food yearly, around 4 billion tons, to feed everyone, but around one-third of all food made, approximately 1.3 billion tons of fruit, vegetables, dairy and meat, goes to waste, according to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, that’s enough calories to feed every undernourished person.

Experts said that other parts of the growing food insecurity problem are rising food prices and malnutrition, proving most detrimental to women and children.

“When you look at the food price crisis, it’s particularly foods that are nutritious and are high in vitamins and minerals that these children need that are the most costly,” Saskia Osendarp, executive director of the Micronutrient Forum and co-coordinator of Standing Together for Nutrition, a consortium of nutrition, economics, food and health system experts, told ABC News.

Osendarp added that if women and children cannot afford or have access to healthier, vitamin-rich foods, they risk having micronutrient deficiencies.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres holds a news conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, Nov. 17, 2022.

Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

When food prices increase, households switch to cheaper staple foods and processed foods instead of buying more nutritious — and generally more expensive– foods, such as fruits, vegetables, dairy, meat, decreasing the quality of their diets, Osendarp said in an April op-ed in Nature magazine.

About one in two preschool-aged children and two in three women of reproductive age globally experience at least one micronutrient deficiency, according to a report from the Lancet Global Health.

Malnutrition can also lead to significant health problems, particularly in children, who may develop cognitive and developmental issues, as well as how they perform in school, Osendarp said.

“We call this hidden hunger because you don’t immediately notice it, but you do see it in individuals that lack these critical vitamins,” she said. “It has devastating impacts on their survival, their immunity, their health, but also on their growth and overall development. The impacts will last for a long time.”

At the G20 Summit, Guterres told world leaders that if there isn’t an organized action plan, then affordability issues this year will lead to food shortages in 2023.

Local civilians queue for food distribution in Kherson City, Ukraine, Nov. 16th, 2022.

Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A combine tractor harvests corn in Leland, Miss., Aug. 16, 2022.

Bloomberg via Getty Images, FILE

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also increased food prices, as both countries are important suppliers of wheat, barley, corn and sunflower oil.

In May, Samantha Power, administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development, told ABC “This Week” anchor George Stephanopoulos that Russia’s war in Ukraine had caused global food and fertilizer shortages, resulting in increased prices for consumers and farmers around the world.

“It is just another catastrophic effect of Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine,” Power said at the time.

Over half of the projected global population growth up to 2050 will happen in eight countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines and the United Republic of Tanzania.

According to the U.N., food insecurity in sub-Saharan Africa is at 66.2%, the highest in the world.

Over half of the world’s undernourished live in Asia and more than one-third live in Africa, with the situation worsening because of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a U.N report.

Last month at the Committee on World Food Security, WFP executive director David Beasley said the world is facing threats of mass starvation and that global leaders must act and provide humanitarian support.

ABC News’ Youri Benadjaoud, Julia Jacobo and Gabriel Pietrorazio contributed to this report.