WASHINGTON — Facing a national crisis with a devastating human toll and entrenched partisan divisions, a small group of Senate Republicans and Democrats pushed forward on high-stakes bipartisan talks that seemed unusually promising — right until the moment they collapsed.

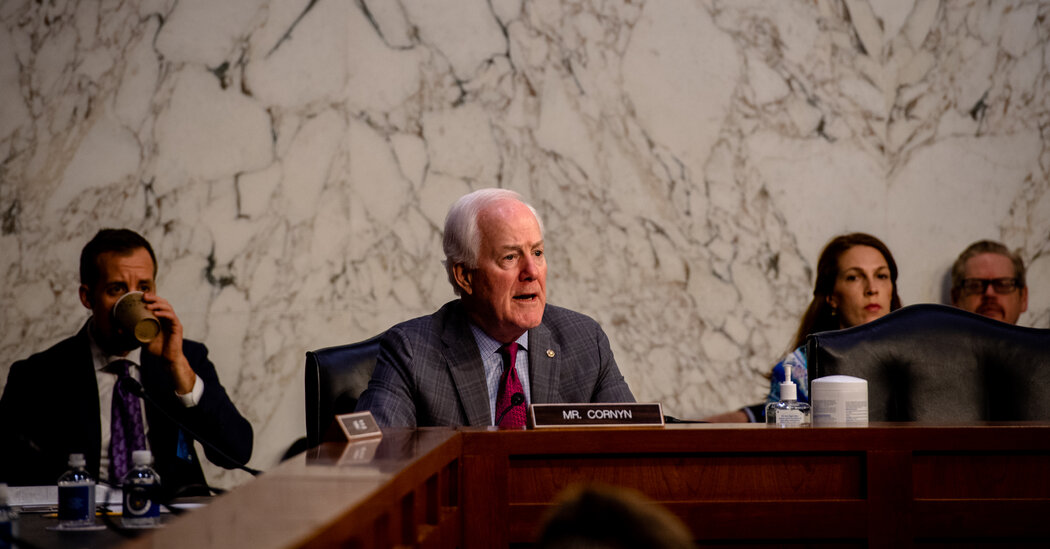

“The rhetoric from Washington has been impressive,” lamented Senator John Cornyn of Texas, a key negotiator for the Republican Party. “But the results have been pathetic.”

The year was 2013, and Mr. Cornyn was talking about immigration, a policy area where he had engaged in multiple rounds of bipartisan talks. But the senator, a four-term Texan, could just as easily have been discussing the negotiations in which he is currently a pivotal player: an improbable round of talks among a small crew of Senate Republicans and Democrats to respond to the epidemic of gun violence in America.

With those discussions reaching a critical stage, Mr. Cornyn is playing a familiar role: the conservative Republican in a room of centrists who can make or break an agreement — and has both sides guessing, to some degree, over which it will be. His presence at the talks — for which he was handpicked by Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the minority leader — means that the far-reaching gun control measures that President Biden and top Democrats are seeking are off the table from the start.

“It has to be incremental,” Mr. Cornyn said in an interview, quickly dismissing Mr. Biden’s push for steps that could not pass the Senate, such as renewing a federal ban on assault weapons, limiting high-capacity magazines or raising the age to purchase a semiautomatic rifle to 21 from 18.

“I don’t think it moved the needle,” Mr. Cornyn said of the president’s speech last week. “If we are going to come up with a solution, it is going to have to come from the Senate and, frankly, I think the White House understands that. The president is not necessarily a unifying figure in today’s politics.”

Neither is Mr. Cornyn. With a top rating from the National Rifle Association, he is viewed with suspicion by liberal activists who have long pressed for gun control legislation and see a cautionary tale in the senator’s involvement in past immigration negotiations.

Proponents of legalizing millions of undocumented immigrants and overhauling the system warn that he has perfected what one called the “Cornyn con,” in which he appears to undertake serious policy negotiations but ultimately pulls out when success is at hand and then blames Democrats for being too partisan.

“The silver hair, the silver tongue, the moderate tone project seriousness; but his pattern is to be cynical and unserious,” said Frank Sharry, the executive director of the pro-immigration group America’s Voice. “He pretends he wants progress even as he undermines it.”

Democrats who are leading the gun talks insist that Mr. Cornyn’s involvement this time is different. To win his support, they concede, any new legislation would need to be much narrower than they would prefer. But they also note that it was Mr. Cornyn who in 2017 teamed with Democrats to negotiate a package of enhancements in federal background checks after a deadly church shooting in his home state.

“It was an example of Senator Cornyn’s ability to reach out across the aisle on a tough topic and find something that made a difference,” said Senator Christopher S. Murphy, Democrat of Connecticut, who is leading the gun talks for his party. The measure, known as Fix NICS, encouraged government entities to supply more records to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. A Navy record of the Texas church gunman’s court-martial for domestic violence had not been submitted, meaning it was not caught in a review for gun purchases.

Mr. Murphy and other Democrats involved in the talks say their experience with Mr. Cornyn gives them hope that some consensus can be found, probably centering around so-called red flag laws that allow guns to be seized from people deemed to be dangerous, as well as mental health measures, school safety funding and adjustments in background checks.

“He’s made it very clear what he is not willing to do, and now we are just exploring what is possible,” said Mr. Murphy, who has become a leading congressional voice on gun safety after the 2012 Sandy Hook school shootings in his home state. “He is not willing to infringe on law-abiding gun owners’ rights. He is not willing to ban weapons.”

“I’ve got a good sense of his no-go areas,” Mr. Murphy said of Mr. Cornyn.

The Texan has made plain what he considers off-limits. When a conservative radio host posted a tweet warning that the senator might back more restrictive gun laws, Mr. Cornyn recirculated the comment with a pointed response: “Not gonna happen.”

“This is a very divisive and emotional issue, but it is also a constitutional right we are talking about,” Mr. Cornyn said in the interview. “I feel very strongly that law-abiding citizens are not the problem here. It is people with criminal and mental health problems.”

While suggesting that raising the age to purchase assault weapons would not clear the Senate, Mr. Cornyn said one idea he was exploring with colleagues was whether juvenile records, which are often sealed or expunged, could be added to the information available for a background check. He suggested that such an expansion could have prevented the 18-year-old gunman in Uvalde from obtaining his weapon.

“Nothing that happened in his past was part of that background check,” Mr. Cornyn said. “We are reaching out to see if there is maybe a mechanism that could make that information available, just like if they were an adult. They would either pass or not pass based on their criminal and mental health record. It is a real gap.”

Democrats and Republicans say that Mr. Cornyn’s backing is essential to broaden support for legislation, given his credibility with his colleagues. He was the No. 2 Republican in the Senate for six years, until term limits forced him out in 2018. He is seen as a contender for Senate Republican leader whenever Mr. McConnell steps aside.

“I think John is deeply motivated to come up with a common-sense set of reforms that would make a difference,” said Senator Susan Collins, Republican of Maine and a participant in one set of gun safety talks, noting that the Uvalde victims were his constituents. “If we were successful in negotiating a package John can sign onto, it will almost certainly pass the Senate and bring us additional Republican votes.”

Elected in 2002 to fill an open seat, Mr. Cornyn, a former Texas Supreme Court judge and state attorney general, cuts an affable figure on Capitol Hill. He is a distinct contrast to his more incendiary home-state counterpart, Senator Ted Cruz, who has summarily rejected new gun legislation.

Mr. Cornyn is a force on the Judiciary Committee, where he has been deeply engaged on nominations, criminal justice overhauls and immigration policy, where compromise on a major rewrite of laws has proved elusive.

Democrats credit him with pulling off modest compromises such as a recent patent abuse bill intended to prevent pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs from coming on the market. On guns, he and Senator Chris Coons, Democrat of Delaware, won a provision in the Violence Against Women Act in March that requires federal authorities to notify local law enforcement when a person fails a background check in an effort to buy a weapon.

“When he wants to reach common ground, he can,” said Senator Richard Blumenthal, Democrat of Connecticut, who co-authored the patent bill with Mr. Cornyn and is also part of the bipartisan gun talks. “But the jury is still out on this one.”

The talks being conducted by Mr. Murphy are unfolding with two separate groups, one of which includes Mr. Cornyn and Senator Kyrsten Sinema, Democrat of Arizona, with whom Mr. Cornyn has worked closely on immigration issues.

Despite the Memorial Day recess, participants said that talks proceeded “dawn to dusk” in a drive to assemble legislation as soon as this week and that the congressional break did not seem to slow momentum, as it has in the past.

Given the history of failures on new gun proposals and the fact that Mr. Cornyn is seen as the gauge of what is acceptable to Republicans, no one is ready to declare that an agreement can be reached. But they do say they see opportunity.

“I am prepared to fail,” Mr. Murphy said. “But every single day, we are getting closer to success, not farther away.”

Mr. Cornyn has not committed to anything, but he says the negotiations are worth the effort.

“Hope springs eternal,” he said. “I’m happy to be involved in something that is so important that could, like our Fix NICS bill, save lives.”