(Bloomberg) — Britons confronted by staggering costs this winter are turning down the heating and putting on the jumpers, and that matters for energy markets.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Keeping the thermostat a few degrees cooler than usual could reduce residential gas consumption by as much as 23%, according to a BloombergNEF forecast. That would be enough to stave off forced rationing and carry households comfortably through the coldest of the last 30 winters, giving suppliers a bit of a cushion while seeking replacements for dwindling Russian flows.

Regulator Ofgem warned the country faces a “significant risk” of gas shortages in coming months, and Britain’s grid operator said there could be three-hour power cuts on cold, calm days. Those flares attracted attention, with customers doing some belt-tightening even before winter’s arrival. About three-quarters of households are expected to make behavioral changes such as reducing the amount of time the heating is on and not using it in every room, according to modeling by Lane Clark & Peacock LLP.

Additional layers of clothing and bedding also help when nights get colder. University student Hannah Kinnane lives in Brighton with four family members, including her 84-year-old grandmother, who suffers from heart arrhythmia.

“With the bills going up, we’re planning on keeping the heating off until at least November,” Kinnane, 20, said in a private message on Twitter. “To keep warm, we’ve all been congregating in the same room for three or four hours before going to bed with extra blankets.”

All told, those changes could reduce energy consumption in an average household by as much as 20%, said Steven Ashurst, head of heat at an LCP unit.

“We are all hoping for a mild autumn and winter heating season,” he said. “People will try to manage without their heating for as long as possible.”

The government so far has prioritized reducing costs for consumers over pushing conservation. The European Union raised concerns about the UK and Germany providing billions of dollars of support for energy bills without addressing demand.

Rationing is rare in the UK, but not unknown. Three-day work weeks were introduced in the early 1970s after strikes by coal miners and railroad workers curbed power generation.

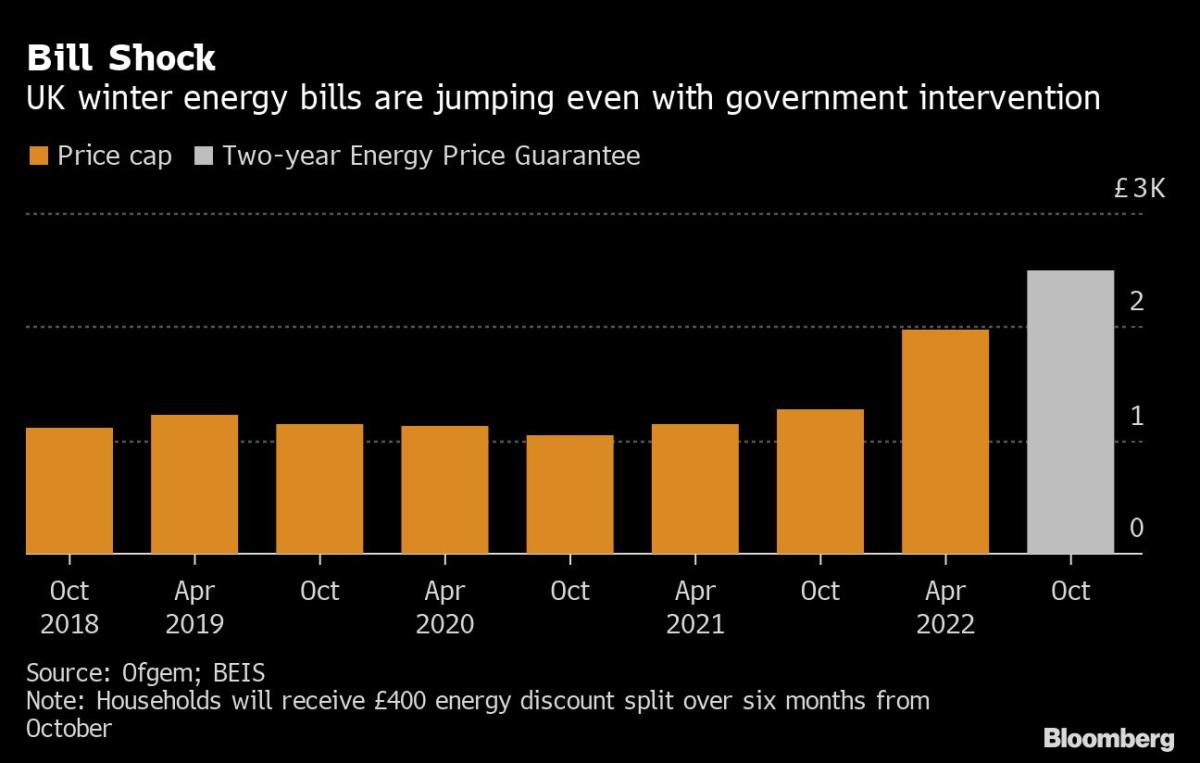

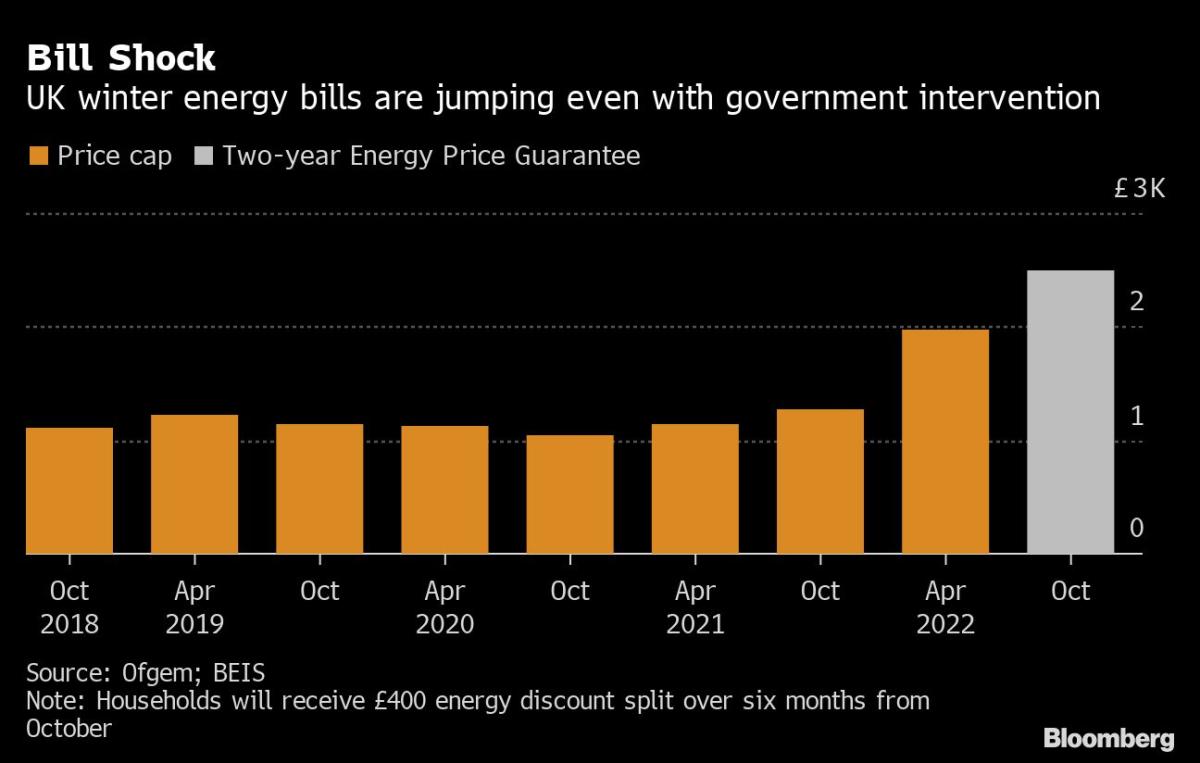

The UK is spending £130 billion ($144 billion) to freeze the unit cost of energy for households for two years. Still, a typical domestic bill will be £2,500 a year, almost double last year’s average.

Europe has a voluntary target to cut gas consumption by 15% this winter, and France unveiled dozens of measures, pledges and incentives to cut energy use by 10% over two years. By comparison, the UK made no estimates, and Prime Minister Liz Truss blocked an energy-saving campaign.

While using less energy helps wallets and can be pitched as part of a war effort to help punish Russia for invading Ukraine, there can be severe health effects associated with the cold.

Spending extended periods at temperatures below 15C (59F) can increase the risk of serious respiratory illness, and temperatures below 14C worsen cardiovascular conditions, according to the Centre for Sustainable Energy charity.

Comfortable indoor temperatures vary — depending on age, health and other factors — but the Met Office forecasting agency recommends at least 18C.

“Consumers are rightly spooked by the promise of high prices, so many will choose a jumper over the thermostat,” said Caspian Conran, an energy markets economist at London-based consultancy Baringa Partners LLP. He estimates residential demand falling by 10%.

With bills rising, fuel poverty campaigners warn of potentially dire consequences for the millions of households that can’t afford to pay. Cold weather contributes to about 265 deaths a month in England and Wales, according to a report published in The Lancet medical journal.

That tally could rise this year, said Peter Smith, director of policy and advocacy for the National Energy Action charity.

A calamity on that scale would overwhelm a National Health Service already pushed to its breaking point by Covid-19 and tight budgets. Hospitals aren’t covered by the heating aid package, so they’re paying tariffs that have doubled or tripled.

Spending more on energy could lead to staff reductions, longer waiting times and potential cutbacks in patient care.

But some experts say energy usage is not a zero-sum game: either turn up the heat and pay a lot or keep it off and shiver.

The most effective way to minimize power consumption during colder months is by improving insulation, said Raman Bhatia, chief executive officer of Ovo Energy Ltd., noting the average UK home loses heat three times faster than those in Germany or Sweden.

He also recommended using “smart-home” technology to boost efficiency. Ovo, the nation’s third-biggest household supplier, is training customer-service agents to offer more advice and audit homes.

“Small changes in consumer behavior could account for substantial changes in the gas balance,” said Stefan Ulrich, a European gas analyst at BNEF.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.