LONDON (AP) — Staffers at the World Health Organization’s Syria office have alleged that their boss mismanaged millions of dollars, plied government officials with gifts — including computers, gold coins and cars — and violated the agency’s own COVID-19 guidance as the pandemic swept the country.

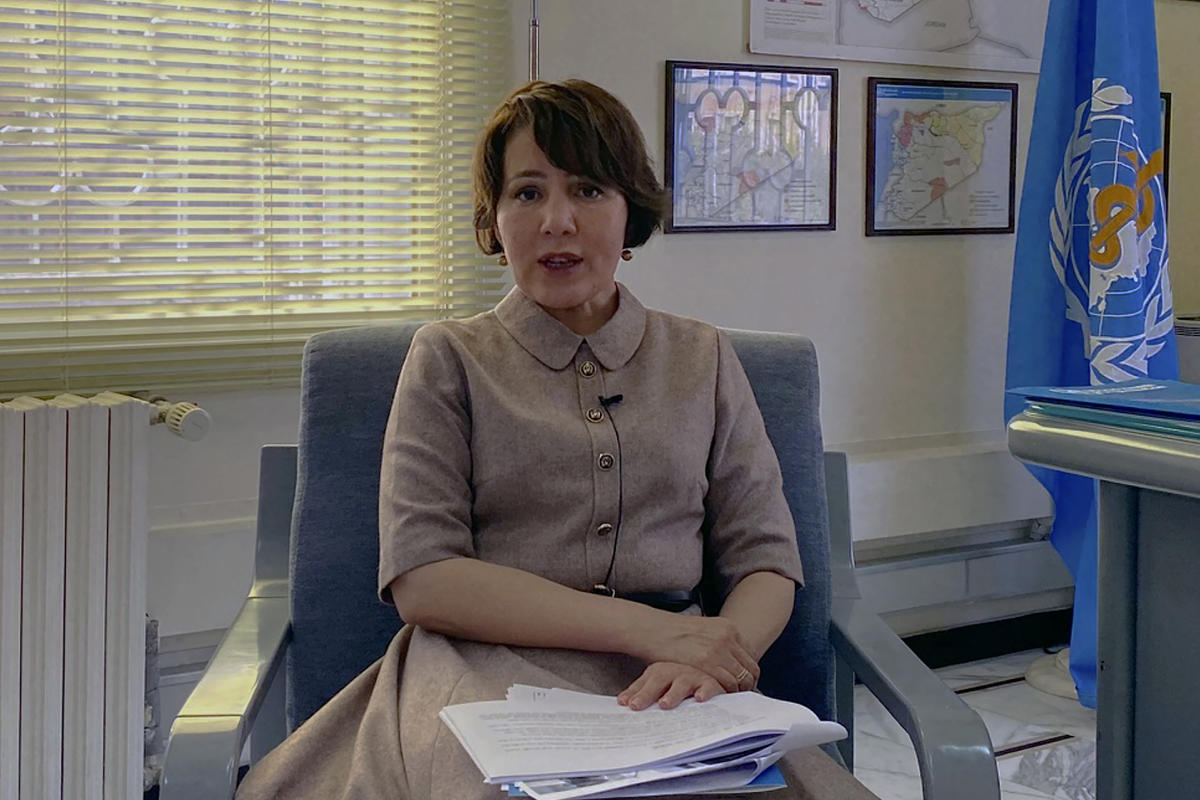

More than 100 confidential documents, messages and other materials obtained by The Associated Press show WHO officials told investigators that the agency’s Syria representative, Dr. Akjemal Magtymova, engaged in abusive behavior, pressured WHO staff to sign contracts with high-ranking Syrian government politicians and consistently misspent WHO and donor funds.

Magtymova, a Turkmenistan national and medical doctor, declined to respond to questions about the allegations, saying that she could not answer, “due to (her) obligations as a WHO staff member.” She described the accusations as “defamatory.”

The complaints from at least a dozen staffers have triggered one of the biggest internal WHO investigations in years, at times involving more than 20 investigators.

WHO confirmed in a statement that a probe was ongoing, describing it as “protracted and complex.” Citing issues including confidentiality and the protection of staff, WHO would not comment on Magtymova’s alleged wrongdoing.

WHO’s Syria office had a budget of about $115 million last year to address health issues in a country riven by war — one in which nearly 90% of the population lives in poverty and more than half desperately need humanitarian aid.

For the past several months, WHO investigators have been probing incidents including a party that Magtymova ostensibly threw to mostly honor her own achievements at the U.N. agency’s expense, her request to staff in December 2020 to complete a flash mob dance challenge, and claims Magtymova “provided favors” to senior politicians in Syria, in addition to meeting surreptitiously with Russian military, potential breaches of WHO’s neutrality as a U.N. organization.

In one complaint sent to WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in May, a Syria-based staffer wrote that Magtymova hired the incompetent relatives of government officials, including some accused of “countless human rights violations.”

In May, WHO’s regional director in the Eastern Mediterranean appointed an acting representative in Syria to replace Magtymova after she was put on leave — but she is still listed as the agency’s Syria representative in its staff directory.

Numerous WHO staffers in Syria have told the agency’s investigators that Magtymova failed to grasp the severity of the pandemic in Syria and jeopardized the lives of millions.

At least five WHO personnel complained to investigators that Magtymova violated WHO’s own COVID-19 guidance. They said she did not encourage remote working, came to the office after catching COVID and held meetings unmasked. Four WHO staffers said she infected others.

In December 2020, deep in the first year of the pandemic, Magtymova instructed the Syria office to learn a flash mob dance popularized by a social media challenge for a year-end U.N. event.

“Kindly note that we want you to listen to the song, train yourself for the steps and shoot you dancing over the music to be part of our global flash mob dance video,” wrote WHO communications staffer Rafik Alhabbal in an email to all Syria staff. Magtymova separately sent a link to a YouTube website, which she described as “the best tutorial.”

Multiple videos show staffers, some wearing WHO vests or jackets, performing “ the Jerusalema challenge ” dance in offices and warehouses stocked with medical supplies, at a time when senior officials at WHO Geneva were advising countries to implement remote working when possible and to suspend all non-essential gatherings.

Internal documents, emails and messages also raise serious concerns about how WHO’s funds were used under Magtymova, with staffers alleging she routinely misspent limited donor funds meant to help the more than 12 million Syrians in dire need of health aid.

Among the incidents being probed is a party Magtymova organized last May, when she received an award from Tufts University, her alma mater. Held at the exclusive Four Seasons hotel in Damascus, the catered party included a guest list of about 50, at a time when fewer than 1% of the Syrian population had received a single dose of COVID-19 vaccine.

The evening’s agenda featured remarks by the Syrian minister of health, followed by a reception and nearly two hours of live music. WHO documents show while the event was called to celebrate WHO’s designation of 2021 as the Year of Health and Care Worker, the evening was devoted to Magtymova, not health workers. The cost, according to a spreadsheet: more than $11,000.

Other WHO officials raised concerns about Magtymova’s spending, saying she was involved in several questionable contracts, including a transportation deal that awarded several million dollars to a supplier with whom she had personal ties.

At least five staffers also complained Magtymova used WHO funds to buy gifts for the Ministry of Health and others, including “very good servers and laptops,” gold coins and cars. The AP was not in a position to corroborate their allegations. Several WHO personnel said they were pressured to strike deals for basic supplies like fuel with senior members of the Syrian government.

The accusations regarding WHO’s top representative in Syria come after multiple misconduct complaints at the U.N. health agency in recent years, including sexual abuse in Congo and racist behavior by the top WHO official in the Western Pacific.

Javier Guzman, director of global health at the Center for Global Development in Washington, said the latest charges regarding WHO’s Magtymova were “extremely disturbing” and unlikely to be an exception.

“This is clearly a systemic problem,” Guzman said. “These kinds of allegations are not just occurring in one of WHO’s offices but in multiple regions.”

He said though Tedros was seen by some as the world’s moral conscience during COVID-19, the agency’s credibility was severely damaged by reports of misconduct. Guzman called for WHO to publicly release any investigation report into Magtymova and the Syria office.

WHO said investigation reports are “normally not public documents,” but that “aggregated, anonymized data” in some form would be made publicly accessible.

____

Sarah El-Deeb in Beirut contributed to this report.