It’s one of the most puzzling questions for Democrats in American politics: Why is the political system so unresponsive to gun violence? Expanded background checks routinely receive more than 80 percent or 90 percent support in polling. Yet gun control legislation usually gets stymied in Washington and Republicans never seem to pay a political price for their opposition.

There have been countless explanations offered about why political reality seems so at odds with the polling, including the power of the gun lobby; the importance of single-issue voters; and the outsize influence of rural states in the Senate.

But there’s another possibility, one that might be the most sobering of all for gun control supporters: Their problem could also be the voters, not just politicians or special interests.

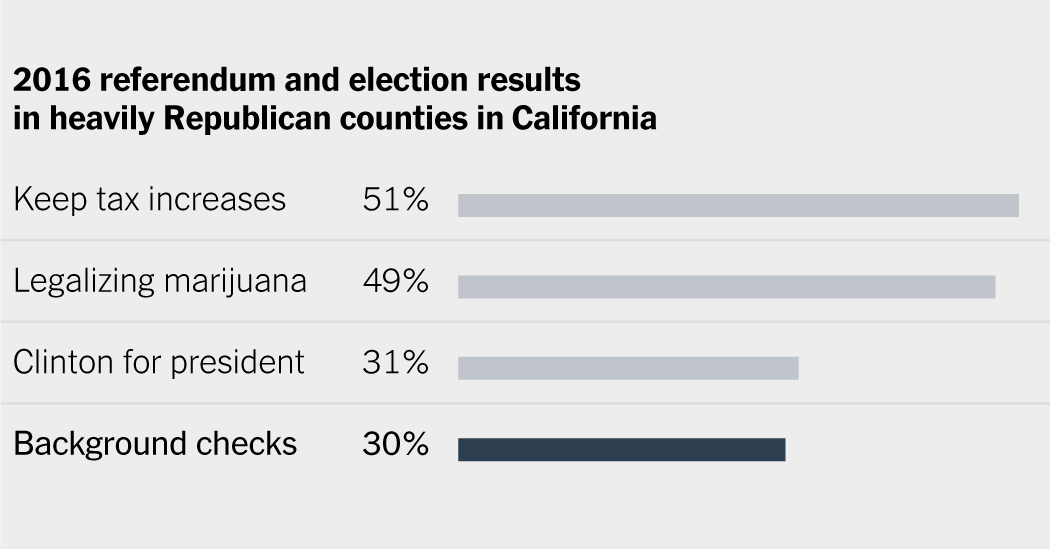

When voters in four Democratic-leaning states got the opportunity to enact expanded gun background checks into law, the overwhelming support suggested by national surveys was nowhere to be found. Instead, the initiative and referendum results in Maine, California, Washington and Nevada were nearly identical to those of the 2016 presidential election, all the way down to the result of individual counties.

Hillary Clinton fared better at the ballot box than expanded background checks in the same states, most on the same day among the same voters.

The usual theories for America’s conservative gun politics do not explain the poor showings. The supporters of the initiatives outspent the all-powerful gun lobby. All manner of voters, not just single-issue voters or politicians, got an equal say. The Senate was not to blame; indeed, the results suggested that a national referendum on background checks would have lost. And while the question on every ballot was different and each campaign fought differently as well, the final results were largely indistinguishable from one another.

To be sure, background checks could prove more politically resonant in 2022 or in the future than they were in 2016. Public support for new gun restrictions tends to rise in the wake of mass shootings. There is already evidence that public support for stricter gun laws has surged again in the aftermath of the killings in Buffalo and Uvalde, Texas. While the public’s support for new restrictions tends to subside thereafter, these shootings or another could still produce a lasting shift in public opinion.

But the poor results for background checks suggest that public opinion may not be the unequivocal ally of gun control that the polling makes it seem.

The possibility that one of the most popular policies in polling could run behind Mrs. Clinton at the ballot box raises important questions about the utility of issue polling, which asks voters whether they support or oppose certain policies. While these questions probably tell us something about public opinion, it may tell us quite a bit less about the political landscape than many assume.

For Democrats, the story is both unsettling and familiar. Progressives have long been emboldened by national survey results that show overwhelming support for their policy priorities, only to find they don’t necessarily translate to Washington legislation and to popularity on Election Day or beyond. President Biden’s major policy initiatives are popular, for example, yet voters say he has not accomplished much and his approval ratings have sunk into the low 40s.

The inability of Democrats to capitalize on an apparent policy majority has fueled intraparty recriminations about messaging and strategy. These debates often assume that Democrats ought to fare better but that they get in the way of their own popular agenda. Alternately, progressives fear that conservatives — through television and social media — can use scare tactics about socialism and demographic change to sever the connection between public opinion and political outcomes.

All of these theories may have merit, but the results of referendums add another possibility: The apparent progressive political majority in the polls might just be illusory. It simply may not exist for practical purposes. And the tendency for referendum results of all ideological colors to underperform the polls may betray an overlooked dimension of public opinion: a tendency to err toward the status quo.

It would be wrong to say that the results simply prove the polls “wrong,” strictly speaking. Initiative and referendum results are not a perfect or simple measure of public opinion. The text of the initiatives is different and more complex than a simple national poll question. Some voters who may support a proposal in the abstract may ultimately come to oppose its detail. The context is very different as well. The vote follows a referendum campaign that can shift public opinion.

And the act of voting to enact an initiative into law carries far more responsibility and consequence than a carefree response on a survey. When in doubt, many voters may adopt a lowercase “c” conservative position in the ballot box. All together, it is no surprise that initiatives and referendums tend to underperform their support in the polls.

But the difference between the poll findings and the gun referendum results is especially large. It is an order of magnitude larger than on other issues, including other referendums in the same states on the same day on hot-button topics like raising the minimum wage, expanding Medicaid or legalizing marijuana. These initiatives all fared far better in Trump country than background checks, even though they would have been expected to receive less support based on the polls.

Those polls have shortcomings of their own. Many voters hold relatively weak views about specific policy items. They may be especially likely to say they “support” policies in a survey, where “acquiescence bias” can lead respondents to agree with what’s being asked of them. Those attitudes might shift quickly once an issue receives sustained political attention.

“When we see that initiatives consistently underperform lopsided issue polling, then that suggests that there is a common pattern at work,” said John Sides, a professor at Vanderbilt who has researched public opinion polling in ballot initiatives. “When seemingly popular proposals are subjected to counterarguments in a competitive campaign and when voters have the responsibility of changing policy (as opposed to just answering survey questions), then the results differ.”

The results of other poll questions about gun control might help explain why the arguments against background checks have proved so resonant. Americans split roughly equally on whether gun laws should be stricter. Less than half say they are dissatisfied with the nation’s gun laws because they’re not strict enough. The public splits roughly evenly on whether Democrats or Republicans can be trusted more on guns. Even the National Rifle Association has been fairly popular.

The findings suggest that whatever large majority appears to exist for background checks is prone to evaporate in a campaign, as Republican-leaning voters who support gun rights can quickly be swayed with appeals to their more abstract and deeply felt concern on the issue.

Gun control opponents are not the only ones who benefit from this phenomenon. Health care reform started out as popular, until the Affordable Care Act was actually proposed and debated. Carbon taxes earn broad national support, but carbon tax initiatives in environmentally friendly Washington State lost twice decisively.

Liberals can benefit, too. Voter identification requirements and parental notification for abortion receive overwhelming support in the polls, but moderate and liberal voters who back abortion or voting rights can quickly be convinced that these modest initiatives pose a more fundamental threat to voting or abortion rights. These initiatives have underperformed at the ballot box by nearly as much as background checks.

Still, a broad challenge to the utility of issue polling is more inconvenient for progressives than conservatives. Democrats have a more expansive legislative agenda than Republicans, and public polling has often given them confidence in the political wisdom of their agenda. If the public’s operational liberalism functions only in an interview with a pollster, not at the ballot box, it may not count for much.