This eclipse has concluded. If you missed it, sign up for The Times Space and Astronomy Calendar to get a reminder of future events on your personal digital calendar.

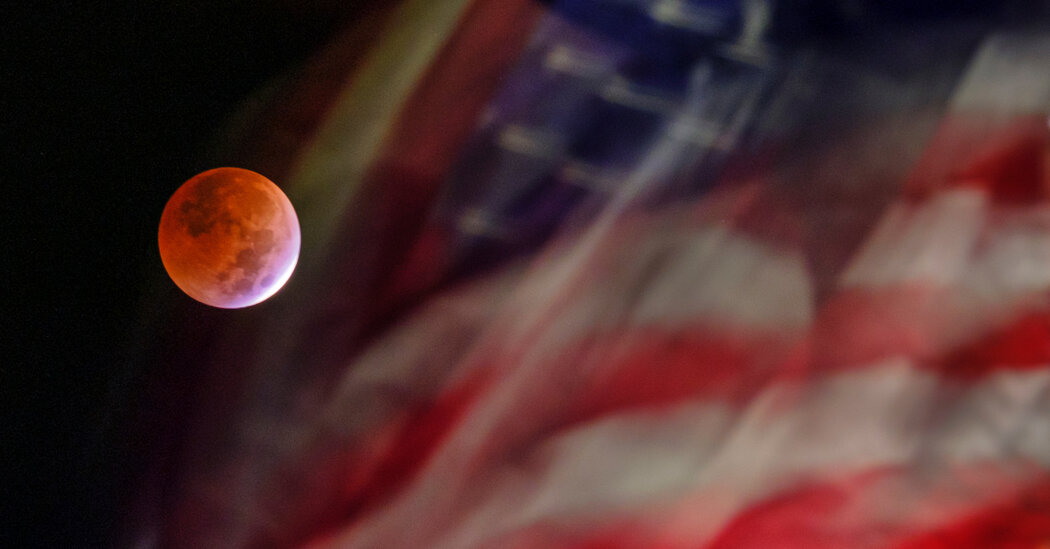

During the early hours on Tuesday, darkness will slip across the face of the moon before it turns a deep blood red. No, it isn’t an Election Day omen — it’s one of the most eye-catching sights in the night sky.

Anyone awake in the United States will have a front-row seat as the sun, the Earth and the moon line up, causing the moon to pass through Earth’s shadow in the last total lunar eclipse until 2025.

“To me, the most significant thing about a lunar eclipse is that it gives you a sense of three-dimensional geometry that you rarely get in space — one orb passing through the shadow of another,” said Bruce Betts, the chief scientist at the Planetary Society.

Here’s what you need to know about viewing the eclipse.

When and where to watch the eclipse

In North America, observers on the West Coast will get the best view. At 12:02 a.m. Pacific time, the moon will enter the outer part of Earth’s shadow and dim ever so slightly. But the total phase of the eclipse — the true star of the show — won’t begin until 2:16 a.m. That phase is called totality, when the moon enters the darkest part of Earth’s shadow and shines a deep blood-red hue. Totality will last for roughly 90 minutes until 3:41 a.m., and by 5:56 a.m. the moon will have returned to its well-known silvery hue.

“The big issue here will be that it’s before Election Day,” said Andrew Fraknoi, an astronomer at the University of San Francisco. “I joke around that many people are so nervous about Election Day this year that maybe they’ll be up all night, and they can watch it.”

Viewers on the East Coast, on the other hand, will have to set their alarms early. Although they won’t be able to watch the entire eclipse, they can catch totality, which will run from 5:16 a.m. Eastern time to 6:41 a.m., roughly when the moon sets for the most northeastern portions of the United States. Early risers should look to the northwestern horizon to catch the ruby moon.

For those in the Midwest, totality will stain the moon red from 4:16 a.m. Central time until 5:41 a.m. And for those in the Rocky Mountains, totality will occur one hour earlier.

Forecasters predicted rainy conditions along the West Coast overnight, which could affect viewing of the eclipse. And some cloudy skies or fog could appear in central parts of the United States, from Minneapolis down to cities in Texas. Weather reports suggested mostly clear conditions along much of the Eastern Seaboard overnight.

Beyond North and Central America, sky-watchers will be able to observe the eclipse in East Asia and Australia, where it will occur in the early evening after moonrise. NASA’s visibility map provides further details.

No matter where you are and which phase of the eclipse is happening, it is safe to watch with your unaided eyes.

What makes a blood moon?

It may come as a surprise that the moon doesn’t simply darken as it enters Earth’s shadow. That’s because moonlight is usually just reflected sunlight. And while most of that sunlight is blocked during a lunar eclipse, some of it wraps around the edges of our planet — the edges that are experiencing sunrise and sunset at that moment. That filters out the shorter, bluer wavelengths and allows only redder, longer wavelengths to hit the moon.

“The romantic way to look at it is that it’s kind of like seeing all the sunsets and sunrises on the Earth at one time,” Dr. Betts said.

That outlook is drastically different from those of some of our ancestors. “For many cultures, the disappearance of the moon was seen as a time of danger, chaos,” said Shanil Virani, an astronomer at George Washington University.

The Inca, for example, believed that a jaguar attacked the moon during an eclipse. The Mesopotamians saw it as an assault on their king. In ancient Hindu mythology, a demon swallowed the moon.

But not all lunar eclipses result in the deep red that led to the “blood moon” nickname. Just as the intensity of a sunrise or a sunset can vary from day to day, so can the colors of an eclipse. It’s mostly dependent on particles in our planet’s atmosphere. Wildfire smoke or volcanic dust can deepen the red hues of a sunset, and they can also affect the eclipsed moon’s hue. But if the atmosphere is particularly clear during a lunar eclipse, more light will get through, causing a lighter red moon, perhaps one that is even a ruddy orange.

Using eclipses to study exoplanets

The color of the moon can therefore reveal signatures from our own atmosphere — a trick that could be used for future observations of planets around distant stars.

Astronomers don’t typically observe exoplanets directly. Instead, they look for transits, or telltale blips when a planet crosses in front of its parent star. During such a time, starlight is filtered through the exoplanet’s atmosphere in the same way that, during a lunar eclipse, sunlight passes through Earth’s atmosphere before it hits the moon.

That means astronomers can treat a lunar eclipse as a proxy for an exoplanet transit. “It’s basically using the moon as a mirror to observe the Earth transiting the sun,” said Allison Youngblood, an astronomer at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

In January 2019, Dr. Youngblood and her colleagues trained the Hubble Space Telescope on the moon during a total lunar eclipse. Because chemicals in Earth’s atmosphere should block certain wavelengths of sunlight from reaching the moon — thus leaving dips in the observed spectrum — Dr. Youngblood’s team was able to detect ozone.

“It’s kind of like a practice round,” Dr. Youngblood said. By treating Earth as an exoplanet, astronomers can double-check that they correctly detect atmospheric details when observing other stars.

But Manisha Shrestha, an astronomer at the University of Arizona, has another idea in mind. She plans to observe the lunar eclipse on Tuesday from the Bok Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona with the hope of spotting not only certain chemicals within our atmosphere, but also their distribution.

This technique has never been performed on exoplanets before and could mean that future detections won’t simply reveal whether an exoplanet has clouds, but whether those clouds smother the world in a thick layer or whether they are slightly uneven, as clouds on Earth are. If those clouds were both uneven and composed of water vapor, that exoplanet just might be Earth 2.0.

But you don’t need a scientific reason to enjoy the eclipse. Astronomers agree that it’s the perfect opportunity to take a break from the politics of election season and simply ponder the cosmos.

“From the cosmic perspective, our problems are temporary things — things that are passing fancies of the human species,” Dr. Fraknoi said. “The eclipse connects you to cycles and rhythms that are much older.”