African countries are among those hoping to increase their exports of gas to the European Union, after the EU committed to reduce its reliance on Russian supplies following the invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s suspension of deliveries to Poland and Bulgaria over their refusal to pay in roubles, the Russian currency, was a stark reminder of the threat facing the Eurozone. Russia has the largest natural gas reserves in the world and is the largest exporter, accounting for around 40% of Europe’s imports.

The EU wants to cut supplies by two-thirds by the end of the year and become independent of all its fossil fuels by 2030.

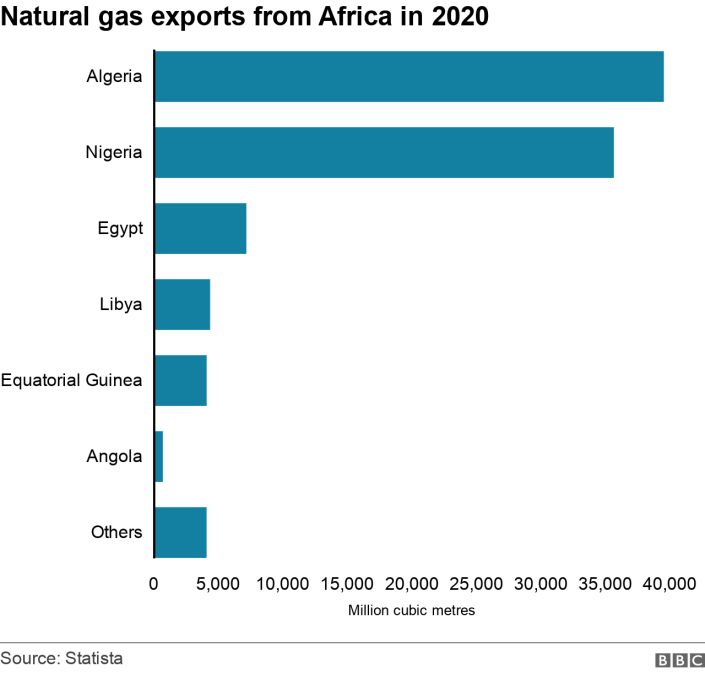

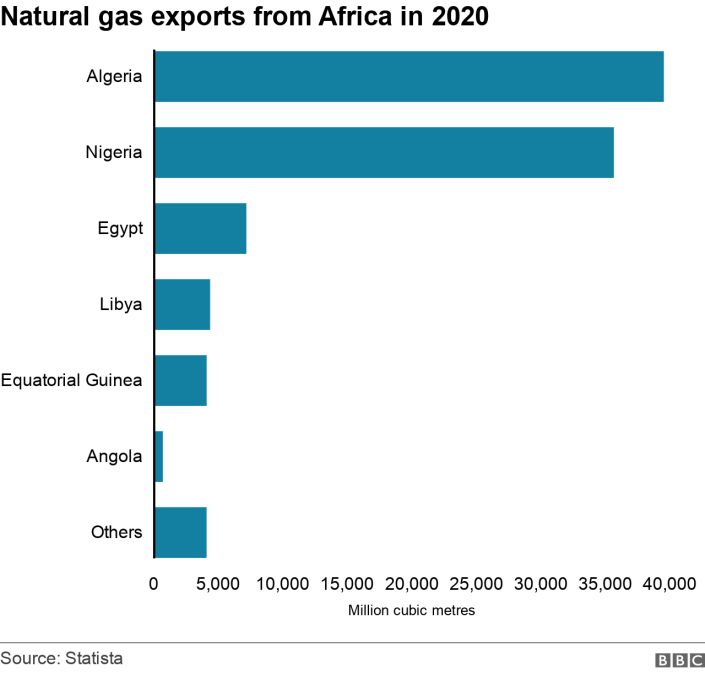

However, energy economist Carole Nakhle says that with the combined exports of Africa’s big players in the industry – Algeria, Egypt and Nigeria – amounting to less than half of what Russia supplies to Europe, they are “unlikely at the moment to compensate for any losses in Russian supplies”.

“The good news is there will be greater interest in countries that already have the resources to replace Russian gas and Africa is in a very good position. We’re going to see more investment,” she says.

However, this will take time because if various logistical issues in the continent’s major exporters.

Algeria is well positioned to benefit from the EU’s shift in energy policy. The North African country is the region’s biggest natural gas exporter and currently enjoys well developed gas connectivity infrastructure with Europe.

Last month Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi signed a new gas supply deal with Algeria to increase gas imports by around 40%.

It was Italy’s first major deal to find alternative supplies following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

However, there are concerns over Algeria’s ability to boost capacity due to rising domestic consumption, underinvestment in production and political instability, says Uwa Osadieye, the senior vice-president of Equity Research at FBNQuest Merchant Bank.

He points out that the amount of gas exported from Algeria to Europe has fallen sharply recently because of a dispute with Morocco, leading to the closure of a vital pipeline to Spain, from 17 billion cubic feet a year to around nine billion.

Pier Paolo Raimondi, an energy research fellow at Rome’s Instituto Affari Internatzionali, echoes these concerns.

“The agreement will allow them to exploit the available pipeline transportation capacity and it could gradually provide increasing volumes of up to nine billion cubic metres per year in 2023 and 2024. [But] we don’t know how fast Algeria can ramp up this production.”

Despite the reservations, the deal has been hailed as a solid first step for Italy, which is the second-largest buyer of Russian gas in Europe.

Italian ministers also travelled to Angola and Congo-Brazzaville, where they agreed new gas deals and Italy is eyeing opportunities in Mozambique in a bid to end its dependency on Russia by mid-2023.

Meanwhile, West African liquified natural gas producer, Nigeria LNG, has been inundated with requests for gas from European countries since the start of the conflict in Ukraine.

At present, Spain, Portugal and France are the three key destination markets for Nigeria LNG’s product and the company is only able to honour its existing contracts with buyers, according to a source who wishes to remain anonymous.

“There is an opportunity to increase production. Today Nigeria LNG is just 72% plant-mobilised, which means there’s still capacity of 28% to utilise, provided they’re able to get the gas, and that’s where the biggest challenge is right now,” the source says.

He cites myriad issues obstructing the company’s ability to step up production, including declining gas wells and a lack of funding for upstream activities.

“They’re things that can be fixed in the short term – between six to 18 months.”

According to Andy Odeh, Nigeria LNG’s General Manager of External Relations and Sustainable Development, discussions are ongoing with natural gas suppliers to resolves these issues and he hopes to increase LNG production levels “from the end of this year onwards,” he says.

A new Nigeria LNG gas project, Train 7, will increase production capacity by 35% from the current 22 million tonnes per annum by 2025.

However, contracts with buyers, largely in Europe, are already in place. Nigeria LNG is also conducting feasibility studies for an additional project, Train 8, to boost supplies further.

The West African state is also a key player in the stalled Trans Saharan Pipeline project – a 4,400km (2,735 mile) natural gas pipeline that would run from Nigeria, through Niger to Algeria.

It would connect to existing pipeline infrastructure in Algeria, linking West African countries to Europe.

The project was mooted in the 1970s, but has been bedevilled by security threats, environmental concerns and a lack of funding.

At a meeting in February, regional officials promised to finally get it going.

However, Kayode Thomas, the head of Bell Oil & Gas, says that another project – the Nigeria-Morocco gas pipeline, which will connect infrastructure in West Africa to Morocco in order to reach Europe – is gaining traction.

“We’re still not sure whether this will cannibalise the Trans Saharan pipeline or run alongside it,” he says.

The project, estimated to cost $25bn ($20bn) and connecting 13 West and North African countries, will be completed in stages over 25 years.

Ms Nakhle says the shift to sourcing gas from Africa could also benefit countries such as Tanzania and Mozambique, although a huge project there run by French giant Total is currently on hold following a major attack by Islamist militants based in the area.

“There is great potential in Africa, but I would say that it’s got to be very limited in the short-term because gas projects take time to materialise,” she says.

But in the medium- and long-term, “you will see greater investment to increase the capacity to bring more gas out of the ground and bring them to Europe”.