“Everywhere the glint of gold.” This is how the British archaeologist Howard Carter infamously recalled his first impression of the dazzling, treasure-filled tomb of Tutankhamun.

On 26 November 1922, he had held up a candle to peer through a tiny breach chiselled in a doorway sealed for three millennia. His patron, Lord Carnarvon, waited anxiously nearby.

The tale of the pair’s incredible archaeological discovery, after years of digging in Luxor with little to show for it, enthralled the world and has been repeatedly retold.

Now, the move of the boy-king’s thousands of treasures to the soon-to-open, state-of-the-art Grand Egyptian Museum is allowing fascinating new research.

And a century on, there are fresh questions about how Tutankhamun became a political icon, whether Carter robbed his tomb and why Egyptians got little credit for helping to find it.

From the start, the one-of-a-kind excavation was dogged by controversy.

Although the rules of the time dictated that the contents of an intact royal tomb should stay in Egypt, it was widely believed there would be efforts to spirit them overseas.

Meanwhile, Carter and Carnarvon, struggling with the global media frenzy, cut a deal with a British newspaper that kept other journalists, including Egyptians, out of the tomb. It created animosity.

Historian Christina Riggs says the pair ended up being seen in Egypt as “very old school, very much aligned with racist attitudes and the powers that be”.

The country had been occupied by British forces in 1882 but gained partial independence in early 1922. Tutankhamun became part of the ongoing struggle to be free of imperial influence.

“This is a powerful symbol, that this king is being reborn just as Egypt is being reborn,” comments Dr Riggs, who wrote Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century.

“Egypt is the mother of civilisation, and Tutankhamun is our father,” sang the Egyptian diva Mounira al-Mahdiya in the 1920s. Meanwhile, the celebrated poet Ahmed Shawqi wrote defiantly: “We refuse to allow our patrimony to be mistreated, or for thieves to steal it away.”

Egyptology’s most famous find owed much to good fortune. Dug into the floor of the Valley of the Kings, debris had long hidden the tomb entrance from robbers and archaeologists alike.

However, the luck of Lord Carnarvon ran out in early 1923. He died, apparently from an infected mosquito bite, although many in the media were quick to attribute it to a pharaonic curse.

Over the next decade, it was left to Carter to unpack the precious treasures in the tomb with his team. He was known as a stubborn, undiplomatic man and his relations with the Egyptian antiquities service, which oversaw the work, could often be antagonistic.

From early on, rumours swirled that he had tried to steal. Now Egyptologist Bob Brier has uncovered firm evidence of thefts.

In his book, Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World, he quotes letters from the philologist Sir Alan Gardiner in which he complains about his “awkward” position after being told by an expert that an amulet and tomb seals Carter had given him were stolen.

“I found Carter was giving things away as souvenirs,” Dr Brier tells me. “He just thought he owned it.”

The sumptuous rooms at Highclere Castle in Hampshire seem far removed from the dusty Valley of the Kings. But the stately home – nowadays known as the setting for the period drama Downton Abbey – was Lord Carnarvon’s ancestral home.

The life-long adventurer, who had once tried to sail around the world, was also an early motorist who narrowly avoided death in a road accident before turning his attention to Egyptology.

In Egypt, “he found his passion for life”, according to the modern-day Lady Carnarvon, who delved into her family’s archive to write The Earl and the Pharaoh.

While he worried about how to finance the costly conservation of his incredible find, she says that she found a note by her relative saying he felt it should stay in Egypt. Lady Carnarvon blames “a terrible myriad of misinformation” in the press for suggesting otherwise.

“He was less interested in treasure and gold than making discoveries,” she says.

Ultimately, Egypt did manage to hold on to the marvels found inside Tutankhamun’s tomb. For decades, they were the prized exhibits of the neo-classical Egyptian Museum in Cairo’s Tahrir Square.

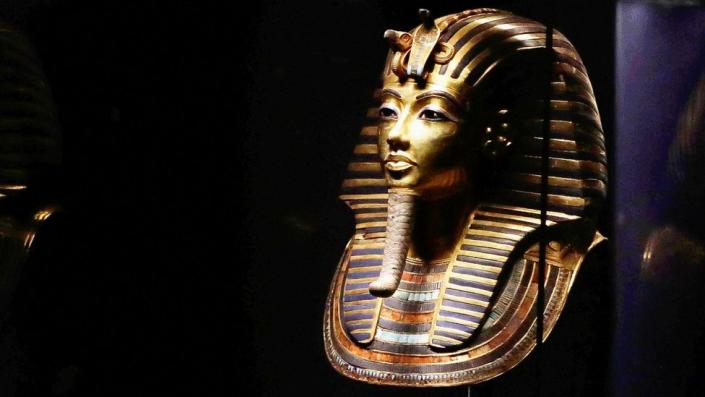

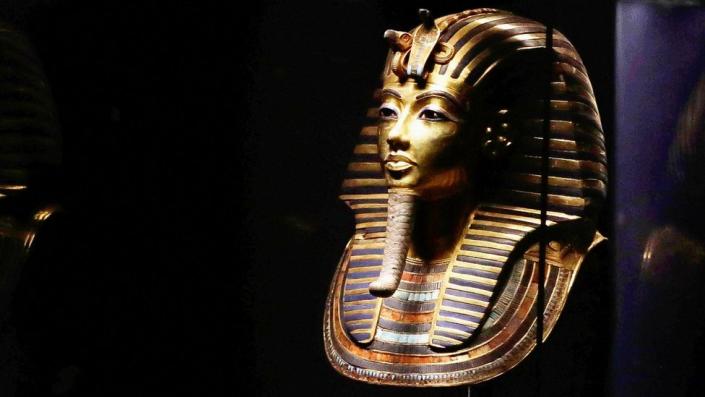

Tutankhamun’s solid gold funeral mask, seen as a masterpiece of ancient art, has become an emblem for modern Egypt.

However, anger remains that Egyptians themselves have remained written out of the official story of the momentous 1922 discovery.

“Most names have disappeared from the archaeological record. We don’t know what they did. What were their reactions?” asks Egyptologist, Monica Hanna.

Besides the Egyptian labourers used to clear the tomb site, Carter also employed skilled Egyptian foremen, including Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said.

Like Carter himself – who had only a limited formal education before travelling to Egypt to join an archaeological expedition aged 17 – they trained on the job.

This year, an exhibition at Oxford University has highlighted the role of the Egyptian workers. But while there are official photographs of them, no record was kept to indicate who was who.

After a lull, the fascination with King Tutankhamun surged in the 1960s and 70s, as Egypt allowed his precious possessions to be loaned to overseas museums for blockbuster exhibitions.

It led to an outbreak of what has been called “Tut-mania” in popular Western culture.

When the Grand Egyptian Museum – one of the largest in the world – opens by the Giza pyramids, probably in 2023, it is expected to fuel new interest. The hope is that it will be a boost for tourism, bringing 5 million visitors a year.

It will show for the first time the entire Tutankhamun collection, some 5,400 items.

“The Grand Egyptian Museum will provide a unique chance to rediscover the tomb in the same way that Howard Carter did 100 years ago,” says Tarek Tawfik, its former director.

Other highlights will be the magnificent, ancient Khufu barge and the 83-tonne statue of Ramses II painstakingly moved from Cairo’s main railway station.

Meanwhile, 100 years on, Tutankhamun continues to inspire new waves of scientific discovery.

Modern conservation work is allowing restoration of fragile artefacts, like his sandals. There is new confirmation that a dagger he owned has an iron blade made from a meteorite.

Theories about the young pharaoh’s life are constantly being remade.

His mummy has been CAT-scanned, undergone facial reconstruction and subjected to DNA analysis. It has built a picture of him as a frail, lame, buck-toothed adolescent suffering from a range of genetic disorders, as a result of in-breeding in the royal family.

However, Dr Brier – known as “Mr Mummy” for his expertise in mummification – now questions the idea that Tutankhamun had a club foot, from looking at his bones. He also notes worn armour and other artefacts in his tomb which show him as a warrior.

Far from the idea of “the fragile pharaoh”, he says, “all of this starts to add to the picture that Tutankhamun at least went into battle”.

After a century of making news headlines, Tutankhamun can boast an impressive afterlife. Just a very different one from what he would ever have imagined.