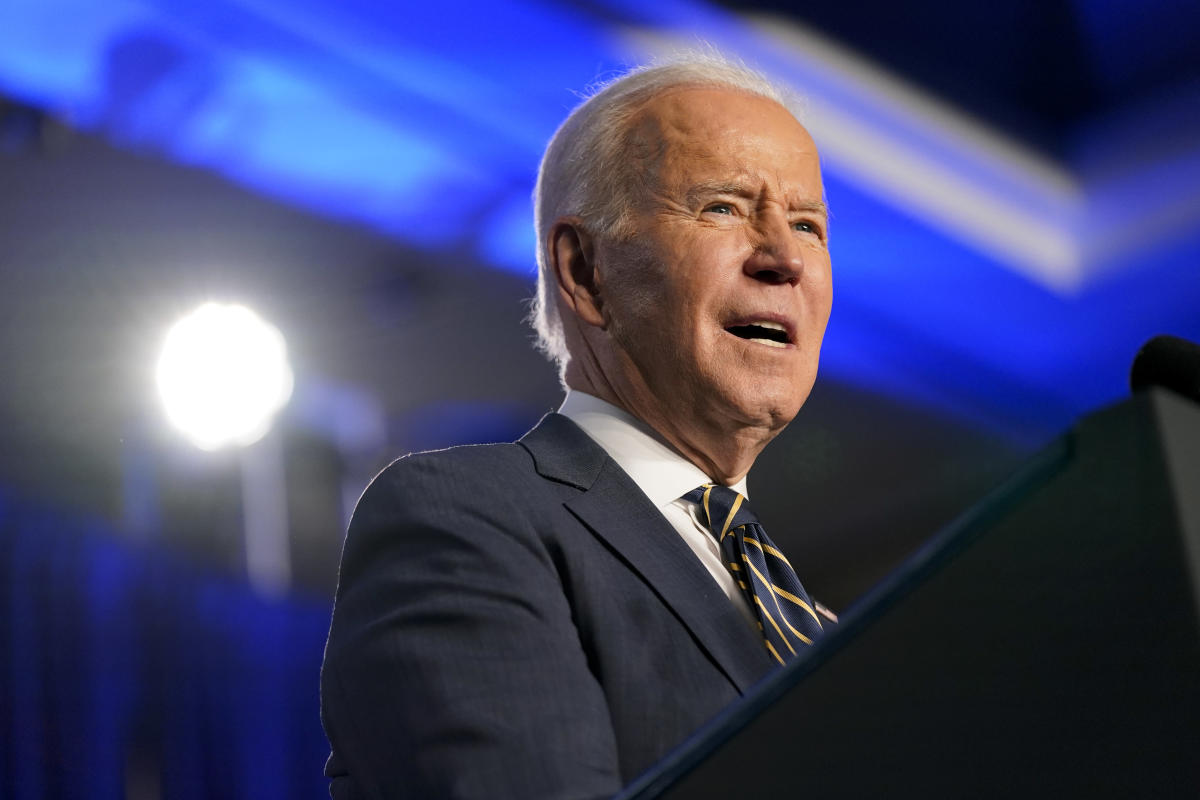

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed an international crisis to the forefront of President Joe Biden’s once domestically focused presidency. It’s also created one of the sharpest policy contrasts yet between Biden and his predecessor.

Trying to keep Russian President Vladimir Putin at bay without escalating the standoff into World War III, Biden has pushed allies to hold together, resisted calls for more direct confrontation, all while attempting to manage the economic impacts back home.

The moment has showcased his pledge to reset America’s relationship with the world after four tumultuous years of former President Donald Trump — and heightened his recurring call for democracies to rally together to confront rising autocracies.

“These are complicated calculations but the overall priority is that Ukraine needs to prevail,” said William Taylor, who was ambassador and acting ambassador to Ukraine under three presidents. “All the steps the Biden administration takes need to be in the name of that goal: to help Ukraine win. Because the outcome of this war will define the world order that is created going forward.”

Taylor, perhaps more than anyone else in the diplomatic corps, understands how different Biden’s approach is from his predecessor’s. Prior to his retirement in January 2020, he was acting ambassador to Ukraine for Trump, who has been out of office for nearly 14 months yet has shadowed over the current conflict.

The same Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, from whom Trump tried to ply damaging information about Biden’s family, has emerged as a heroic symbol of national strength. The same defense systems, the Javelin missiles, that Trump threatened to withhold in a scheme that eventually led to his first impeachment (at which Taylor was a witness), have been instrumental in defending Ukraine.

The same alliance, NATO, that Trump lambasted and tried to undermine, banded together and sent weapons to the front, while Europe and the U.S. have unleashed waves of increasingly punitive economic sanctions on Russia. And the same foreign leader, Putin, with whom Trump repeatedly sided over his own government, has been turned into an international pariah.

Trump’s “America First” foreign policy often turned inward, disregarding traditional alliances in favor of a transactional approach to international relations, which, in turn, often led to cozying up to authoritarians. Some of the United States’ closest allies were left to doubt whether the world’s top superpower could still be relied upon.

Biden, long an internationalist, has taken a nearly polar opposite approach. He has leaned heavily on the importance of alliances while vilifying Putin for commencing a war that grows more violent by the day as Russian forces kill hundreds of civilians as they lay siege to Ukrainian cities.

He has also taken public steps to articulate the limits of his approach. Whereas Trump would openly boast about inflicting wide-scale damage on countries — declaring at a U.N. speech that he’d “totally destroy” North Korea and recently telling golfer John Daly that he threatened Putin with “hitting Moscow” — Biden has ruled out the use of American forces on the ground in Ukraine, or the establishing of a no-fly zone, as either of those measures risked a confrontation with the Russian military and a battle between two nuclear powers.

Retired Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, former director of European affairs for the National Security Council who testified about Trump’s call with the Ukrainian leader, was sharply critical of Biden’s decision to publicly announce the limits to the U.S. response.

“Mr President, you’re inviting disaster & emboldening Putin. This declaration invites Putin to pursue EVERY means to subdue Ukraine,” Vindman tweeted in recent days. “Of course the American people don’t want a war with Russia, but they also don’t want to watch Ukrainians slaughtered. We must do more.”

But foreign policy experts have also praised Biden’s restraint and the broader approach. The president has repeatedly made clear what lines he could not cross, both to make sure the public knows the stakes and to ward off GOP criticism. But White House aides have also said that Biden has laid down such clear markers as a means to exhort allies to help with everything they can while also being reassured that the U.S. would not provoke the conflict further into Europe.

“The Biden administration has instinctively and intelligently realized that the NATO alliance would be their smartest decision,” said James Stavridis, former supreme allied commander of NATO. “The Biden team correctly decided not to frame this as Moscow vs. Washington but as Moscow vs. Washington and vs. Europe and vs. the West and vs. NATO. The White House has largely isolated Putin and has done so by making it clear that the United States was a partner for the rest of the world.”

Biden’s 2020 campaign and first months in office were focused squarely on domestic issues, trying to get the Covid-19 pandemic under control while repairing the economic damage wrought by the virus. But when his attention did turn to international affairs, he worked to establish a clean break from Trump, which often placed the interests of Moscow, Beijing and Riyadh over those of London, Berlin and even Ottawa.

Biden’s first overseas trip wasn’t subtle. His trek across the Atlantic in June 2021 was meant to reassure allies across Europe that he would prioritize cooperation as he rallied the G-7 and NATO countries to stand together against the rising forces of autocracies. It was implicitly and explicitly a reversal from Trump.

To underscore that, he capped off the trip by talking tough to Putin in Geneva, a marked break from Helsinki in 2018 when Trump said he took Putin’s word — over the assessment of U.S. intelligence agencies — about Russian interference in the election two years prior. Biden’s focus on alliances has been the backbone of the nation’s response to Putin, Taylor said.

“The commitment the Biden administration has made to the United States’ allies stands in stark contrast to the apparent lack of commitment from the previous administration,” said Taylor, who also served under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

Trump and his allies have argued that none of the current conflict would have taken place had he been in office, resting their case on the fact that Putin both got along with Trump and feared his unpredictability. Those close to the former president believe that if Trump had been allowed to bring Russia closer into the global fold — he wanted Moscow allowed back into the G-7, returning it to the G8 — that would have quelled Putin’s ambitions. And they assert, without evidence, that Putin would have dared not defy Trump.

But the Biden administration sees it as just the opposite. It has been unsparing in its assessment that Putin was emboldened after watching Trump strain relations with fellow democracies, threaten to leave NATO and largely let Moscow’s malfeasance go unchallenged. Stavridis, who spent four years as the NATO commander in Europe, said Putin also likely misjudged the United States’ willingness to engage on the world stage after two years of being battered and distracted by Covid-19 while still grappling with the divisions that Trump fostered.

“The chaos that Trump helped create, the divisiveness of his term, made it seem to Putin that America was broken and couldn’t respond like it has,” Stavridis said.

While Republicans have attacked Biden for not confronting Putin more directly, such as by declining to help get old Soviet-era jets to Ukraine, they also have largely ignored how portions of their party warmed to Putin during Trump’s term. Instead, the GOP has claimed that Putin was inspired by the chaotic first days of the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan last summer.

“I think that precipitous withdrawal from Afghanistan was a message to people like Putin that America was rethinking our forward-leaning position in the world,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said last week. “And I don’t think if we cut and run in Afghanistan, Putin would have tried this at all.”

Though Biden had wanted to wind down the American presence for more than a decade, many NATO allies felt that they weren’t adequately consulted and were horrified by the withdrawal’s bloody beginning. It intensified questions in global capitals about the future of American international commitments.

Those questions have quieted during the invasion, but they may pick up again as Trump continues to take his first steps back onto the political stage and eye a run for the White House in 2024. Was Biden’s presidency a return to normalcy for American foreign policy or was he an aberration from the Trump approach? And is Biden’s foreign policy holding the international order together, or presiding over a period where American power and influence over authoritarian regimes is on the wane?

Among those awaiting an answer: China, which Biden has identified as the United States’ greatest rival over the next hundred years, and has cannily mostly stayed out of the fray, offering nominal support to Moscow while wondering what lessons can be drawn for a possible future defense of Taiwan.

Aware of those doubts, Biden has tried to use the crisis to drive home the idea that the United States was reclaiming its mantle as the leader of the free world. The first battle in the conflict that will define this century, the one between democracies and autocracies, will be fought and won in Ukraine, he’s argued.

“We see unity among the people who are gathering in cities, in large crowds around the world — even in Russia — to demonstrate their support for the people of Ukraine,” Biden said in his State of the Union address. “In the battle between democracy and autocracies, democracies are rising to the moment, and the world is clearly choosing the side of peace and security.”