For someone who has just been blacklisted by Iran, apparently in response to British sanctions over Tehran’s protest crackdown, Admiral Sir Tony Radakin, the head of Britain’s Armed Forces, appears very relaxed when we meet.

Whether such sangfroid will continue after his beloved Bristol City (a football team he has supported since childhood), has played Championship rivals West Brom on Boxing Day is a moot point. Indeed, this is the concern he raises as we’re leaving the Telegraph offices having just discussed his turbulent first year as Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS), the professional head of Britain’s Armed Forces. In a year that has seen three prime ministers, two monarchs and one war in Europe, the 57-year-old has had much to keep him busy.

The change of political leadership has been the easiest issue to manage, he says, even if inducting a new PM – an individual the head of defence may never have met – into the nuclear firing chain is an odd conversation.

“You go into the bowels, as it were, of No 10 where there’s a room where you can have secret conversations.”

The new PM signs various documents that are crucial parts of the formality of civilian control of the nuclear deterrent.

“Then you have a conversation about letters of last resort,” Admiral Radakin says. He is referring to the messages personally written by the PM to each of the commanding officers in charge of Britain’s four nuclear armed submarines. The letters, held in a safe on board each submarine, are opened only “in a situation where our own nation may have come under nuclear attack or is devastated. The nation’s nuclear deterrent is there and is still functioning in the North Atlantic”.

Instructions are thought to vary from “launch your missiles at your primary targets” to “move to the US and place yourself under command of the President”. Only current and former PMs know what is in the letters to preserve “the sanctity of it”, Admiral Radakin says, and each is shredded unopened when the politician leaves office.

“That, to me, is utterly crucial. We do not want to know what the instructions were. This is something intensely personal to each prime minister.”

Of personal interest to Admiral Radakin is his relationship with other defence leaders. Right now, General Valery Zaluzhny, his opposite number in Ukraine whom he has visited in Kyiv three times this year, is top of that list.

“I penned him a [Christmas] note and gave him a bottle of his favourite whisky: Glenmorangie. I had a nice message back from him yesterday. He is in the thick of it.”

The war in Ukraine has been the biggest issue in CDS’s bulging inbox. Britain’s military and diplomatic support for the country has been a “constant” regardless of political turmoil at home, he says, adding that the “amazing” British and international effort will continue.

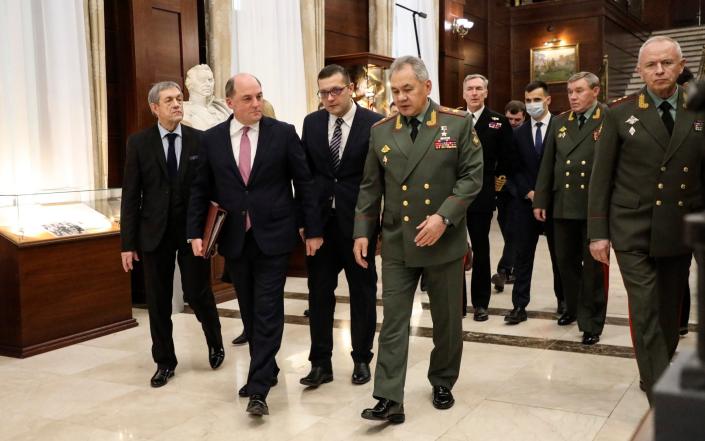

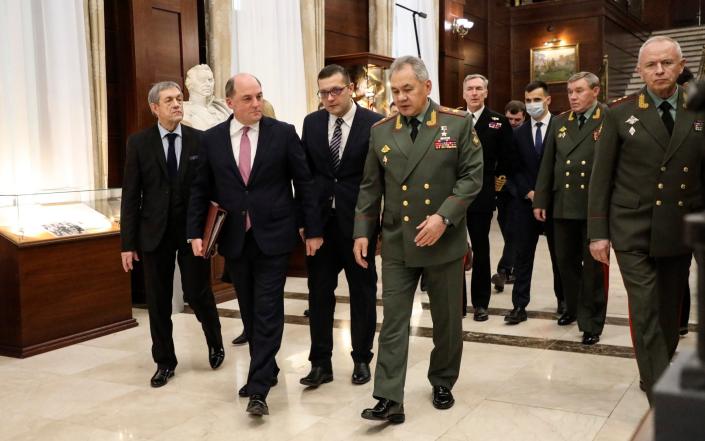

Admiral Radakin visited Moscow in February this year, 10 days before Russian tanks rolled over the border. Unlike Iran, Russia has not sanctioned him, meaning he can go back if he wished. It also means is that he can more easily talk with the head of Russia’s armed forces, General Gerasimov. The two have maintained contact throughout the year, even though relations between Britain and Russia are the worst for decades. “We always said we would communicate but we wouldn’t go into the details of what we’ve discussed. I think he’s been very good at adhering to that.

“I would like them to be even more regular communications. I’d like them to be even stronger, even though they might be difficult conversations. There are relationships that are still ongoing. How can we make the most of them?”

Perhaps with that in mind, Admiral Radakin remarks on Russia’s “respectful” response to the death of Queen Elizabeth II. Despite dreadful relations between Britain and Russia, Putin sent a telegram to King Charles immediately after the announcement of the Queen’s death.

“I wish you courage and perseverance in the face of this heavy, irreparable loss,” he told the new King. “I ask you to convey the words of sincere sympathy and support to the members of the Royal family and all the people of Great Britain.”

Many rolled their eyes at the chutzpah, but Admiral Radakin welcomed any opportunity to keep channels of communication open.

“The danger is you get so wrapped up in [the current situation] you can keep exaggerating. You need to analyse, but not overanalyse and also try and be balanced.

When it comes to the breaking down of (industrial) relations closer to home, however, he refuses to be drawn on what happens when the Armed Forces are called in to cover striking workers.

David Williams, the MoD’s permanent secretary confirmed this week that 1,400 military personnel are being trained for strike cover: 600 for Border Force duty and 600 ambulance drivers. Should service personnel, awarded a maximum 3.75 per cent annual pay rise and with no legal right to withdraw their labour, be compensated for losing their Christmasses to cover for strikes?

“I’ve been really careful to not get drawn into this,” he shoots back. “I’ve taken a very straightforward approach, which is that the Armed Forces serve the nation. We get directed by the government and therefore avoid those political debates.”

However, he concedes that viewing the military as “the go-to” would be “an unusual position for us to arrive at.

“We’re not spare capacity. We’re busy and we’re doing lots of things on behalf of the nation. We’ve got to focus on our primary role.”

Of the covering for striking workers, Admiral Radakin makes the point that doing so “has an impact on individuals”. What, then, of recent reports that military personnel and their families are having to put up with appalling living conditions, despite being the nation’s last resort? Last week the BBC reported on military families having to live in damp, mould-infested housing without heating, waiting weeks for repairs.

“We’ve got to get after them,” Admiral Radakin says. “It is unacceptable for people to have mould in their homes.” He says the contract to manage service accommodation has recently been changed, acknowledging that the new arrangement has “got some issues that we’re dealing with.

“We’ve got a defence infrastructure organisation that is working with the contractors. We quadrupled the number of people that can deal with those complaints. There will be a 24/7 response all the way through the Christmas period. We’ve upped our game and that’s not going to slow down because [of] Christmas. If the organisation is not responding well, [personnel] also need to use the chain of command, because we look after each other no matter what.”

He points out that 98 per cent of families accommodation is either at or exceeds the decent living homes standard set by the government. The figure for single-living accommodation is slightly lower.

I tell him of anecdotal evidence that quartermasters (those in charge of equipment stores) have been giving families without heating sleeping bags for their children. Will they face disciplinary proceedings if caught?

He expresses frustration that such action is necessary. “I absolutely trust in a QM to take the right decision. These are people that in military life take people into battle. We talk about empowerment. That person needs to be empowered to take one of our sleeping bags because he’s got a really dreadful situation with a family that we want to look after. If he thinks the best thing to do is to give them a sleeping bag, we then don’t charge him.”

The big issue, he says, is why families are needing to go to the QM for sleeping bags at all, and that he “despairs” at this “misalignment” experienced by “extraordinary people with extraordinary skills and extraordinary commitment”.

“We’re in a fight with other organisations for talent and it doesn’t match who we are if this is really ropey. We’re trying to be modern, at the front end of technology. This a complete misalignment: about who we are and what we are and what we’re trying to instil; what it means to be in the Armed Forces.”

He is similarly disappointed at suggestions the Armed Forces Compensation Scheme, designed to help serving personnel and veterans (plus families) who suffer illness, injury or death as a result of their service, has become too “adversarial” and is in danger of not meeting the “obligation” to the individual.

“My worry is the length of time it takes to deal with them,” he says. “If you want to join the Armed Forces, we should be laying out a red carpet. If you have been disadvantaged by your service in uniform we should be coming to you and ensuring that that is as smooth a transition as possible.”

I give him the example of a Royal Marine who had a hip and femur shattered by a high velocity bullet when he took part in a raid on a Taliban compound in Afghanistan. His injuries led to further medical conditions but were eventually deemed, for financial compensation purposes, to be the equivalent of a broken leg.

“The bit that frustrates people is that they have made this extraordinary sacrifice and we come across as if we’re quibbling,” agrees Admiral Radakin. “They were prepared to lose their life and that’s the commitment we have. We’ve got to get that right.”

Where, though, does he stand when things do get murky? After all, military operations cast long shadows, not all of them edifying. On Thursday, the Government announced an independent inquiry into allegations of unlawful killings by British soldiers in Afghanistan. Lord Justice Haddon Cave will focus on the period from mid 2010 to mid 2013, specifically on two incidents said to have resulted in the deaths of civilians by the SAS. The inquiry comes in the wake of the 2020 Brereton report into extrajudicial killings in Afghanistan by Australian special forces, after which 2 Squadron of the Australian SAS Regiment was disbanded as a result. The former Australian defence minister, Linda Reynolds, said she felt “physically ill” after reading the report and the chief of the Defence Force at the time, General Angus Campbell, spoke of a “distorted culture” in special forces. Is it the same in Britain?

“We are very confident the right culture exists,” Admiral Radakin asserts. “The reputation of our Armed Forces is super high. Our responsibility is that the same standards apply for everybody. If there have been wrongdoings, then let’s root that out. ”

What of the horrific stories of women in the Armed Forces enduring terrible treatment at the hands of their colleagues, such as 21-year-old Olivia Perks? The officer cadet killed herself in February 2019 at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. A service inquiry said she had been subject to a “complete breakdown in welfare support” during her time in the military.

“There are some things where we have not been getting it right,” he admits. “We’ve got to acknowledge that and allow those people to come forward and have confidence in the system that the culprits will be called out and be dealt with.

“A big thing that we’ve done is [introduce a policy of] zero tolerance for unacceptable behaviour that has a sexual element to it. This should be a positive experience for everybody, because you’re part of this special cadre that serves the nation.”

Admiral Radakin’s own Forces career has arguably been quite different to that of his fellow top brass officers. State educated, he is a qualified barrister with an MA in international relations and defence studies, who continued a legal career alongside his naval service after commissioning into the Royal Navy in 1990. He saw service during the Iran/Iraq Tanker War, worked on counter-smuggling operations in Hong Kong and the Caribbean and served three tours in Iraq – each in command.

In November 2021 he became Britain’s 24th Chief of the Defence Staff. His tenure as First Sea Lord – head of the Navy – plus his ideas for the transformation of the Armed Forces, saw him beat Army rival General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith, a personal friend of then-PM Boris Johnson, to the top job. His drive to modernise the military has led his supporters to call him ‘Radical Radakin’, a somewhat clunky term that has not landed widely. Nevertheless, he is known to have a very good working relationship with his boss, the defence secretary, and the senior civil servants with whom he works daily.

He will turn to his family to relax over Christmas, although with four sons aged between 17 and 24 heading home to Hampshire for the holidays, quite how relaxing a time it will be for him and his wife Louise is open to question. He will spend time with novels and his non-military friends (“I think that’s pretty healthy”). There might be squash or tennis (he is president of the Armed Forces Tennis and Royal Navy Squash Associations, as well as Vice Admiral of the Royal Navy Sailing Association) although he admits he’s not done as much exercise as he would have hoped since taking over the new job.

He will “dip in” to the office to make sure he stays abreast of the war and other essential military business, as “there’s a phenomenal amount of intelligence that you need to keep reading and keep on top of”.

No doubt there will be time to think of future plans too. He expects the government’s refresh of the Integrated Review – the blueprint for Britain’s future foreign and defence policies, due in April next year – will put more flesh on the bones of AUKUS, the defence and technology alliance with Australia and the US, and GCAP, the new Global Combat Air Programme, which will produce a sixth-generation fighter jet in concert with Italy and Japan. These two deals alone, designed in part to counter a rising and increasingly belligerent China, will “shape the next 50, 75 years”.

“They’re big and strategic,” he says with verve. He may be winding down for Christmas, but Admiral Radakin is clearly a man with half his mind, at least, on the future.