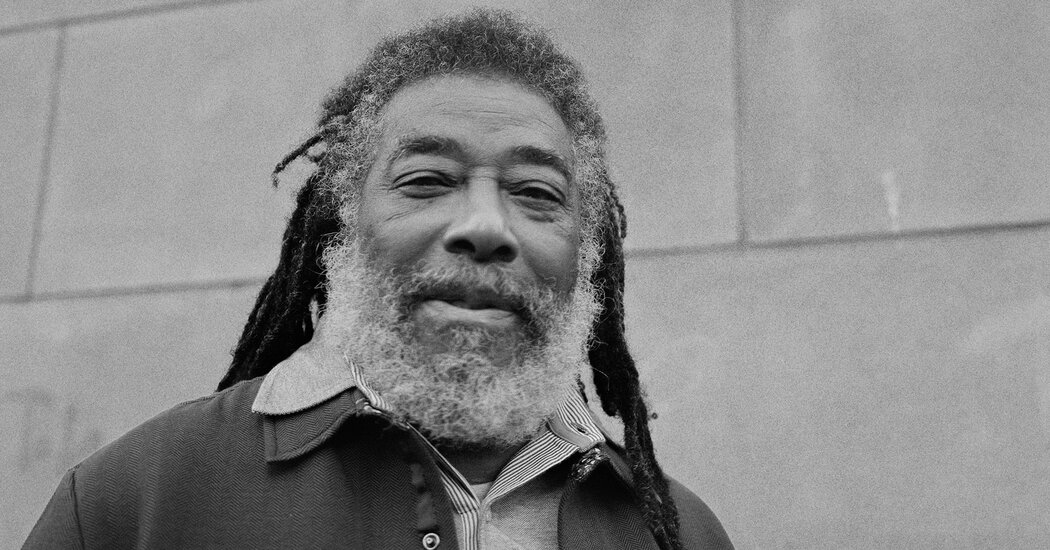

The trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith has played an outsize role in American experimental music for the last 50 years.

His early writings on “creative music” — distinct from both classical and jazz traditions — proved influential to a wide swath of artists in the 1970s, including the pianist and opera composer Anthony Davis.

In more recent years, Smith’s work has incorporated collaborations with the pianist Vijay Iyer and the indie-rock group Deerhoof. Another major project was his “Ten Freedom Summers,” an ambitious, four-hour-plus suite that traces the civil rights movement over a long timeline, including sonic evocations of the Dred Scott case and the Jim Crow era.

The string quartet writing in the suite — the four-CD recording was a finalist for the music Pulitzer in 2013 — gave most listeners their first chance to hear his work in that vein, previously found on just a few low-profile releases. “String Quartets Nos. 1-12,” a new seven-CD boxed set on the Finnish label TUM, fills out that history, revealing his sustained dedication to the format, going back to 1965 and his String Quartet No. 1 (revised in 1982).

In a phone interview from his home in New Haven, Conn., he described string instruments as being in a four-way tie as his “favorite instrument,” along with piano, drums and his cherished trumpet. “The other instruments you can give or take away from me anytime.”

These string pieces rarely start at full throttle. Instead, Smith offers an idea in a contemplative way: a polyphonic passage, a drone or a melody that starts, pauses and repeats with a slight but crucial change. Then those changes begin to proliferate and pile up. Unlike stun-gun experimentalists, Smith has a complex style that sneaks up on you, and feels all the more ravishing for its patient progress.

That style will be familiar to fans of Smith’s work with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (or A.A.C.M.), a collective born on the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s. Autodidacticism was a cornerstone of the association’s ethos, a way to expand on members’ formal training. (During a stint in the Army, Smith studied in a U.S. Military band program; he later studied at the Sherwood School of Music and Wesleyan University.)

By the time he joined the collective in 1967, Smith was already a practiced string quartet composer. “I had already finished at least two versions of String Quartet No. 1,” he said. “When I came to the A.A.C.M. nobody had string quartets, not a single person. And my string quartet had a really big impact — even though nobody ever heard it, because it never was played. But I showed it to people.”

A lot of thought and revision went into the first quartet. “I wrote movement No. 1 over and over for three years,” he said, “because that was my initial training of how to write and how to think about strings.” Also part of the training: studying quartets by Debussy, Bartok, Beethoven and Ornette Coleman.

In the new recording of that first quartet, you can hear traces of Bartok’s advanced harmony and Coleman’s intensity of attack. By the second quartet, though, Smith has found his recognizable, mature language, especially in the pacing.

Smith’s compositional voice and approach to group performance are so strong that listeners may have a hard time teasing out the wide-ranging stylistic inputs. In the liner notes, Smith describes the inspiration of blues guitarists, like B.B. King and Muddy Waters, on his writing for strings.

“If people can’t hear that, I don’t understand what’s wrong,” he said in the interview, with a laugh. “I can hear!”

What about his String Quartet No. 3, “Black Church,” from 1995: Can the way the players tear through sequences of semitones be seen as a tip of the hat to fast-picked streaks of electric-guitar blues?

“Yes, that’s a blues connotation feeling,” Smith said. “Secretly, I say that that string quartet is a blues and a spiritual — at least the first movement.” But the second movement, he said, is about rhythm and repetition.

In his later string quartets, Smith has doubled down on those repetitions. In his notated scores, he often puts brackets over phrases in each string part, with numbers above a given bracket indicating methods of repeating the melodic material.

While his five-line-staff writing is idiosyncratic, it seems conventional compared with the image-based “language scores” in his Ankhrasmation series. (The scores double as detailed artworks, and have been presented in galleries.) Players use a “constructed key” of Smith’s design when interpreting and creating their responses to the symbols and colors on each page. Some of his quartets require players to move back and forth between traditional notation and Ankhrasmation pages, within a single movement.

Navigating this takes practice and dedication. And for decades, it meant there were strikingly few performances of this music. Smith said he stopped approaching established quartets in 2000. But after taking a teaching position at the California Institute of the Arts in 1996, he found a group of talented young musicians in and around Los Angeles who were eager to learn his languages.

That group, now called RedKoral — heard on the boxed set — boasts players with solid contemporary classical résumés. Shalini Vijayan (first violin) has worked with Southwest Chamber Music. Mona Tian (second violin) is part of the celebrated Los Angeles group Wild Up. The cellist Ashley Walters has played with several of Smith’s groups, and records as a solo artist.

And the violist Andrew McIntosh is also a composer whose music was recently performed at the Ojai Festival. McIntosh said Smith had influenced his approach to composition. “I’m more willing now to take risks with the way material unfolds over time than I was five or 10 years ago,” he wrote in an email.

Smith has called the ensemble “the most advanced advocate and performer of my music, ever.” RedKoral’s recent live performance of String Quartet No. 10 — “Angela Davis Into the Morning Sunlight” — helped to show how they’ve achieved this.

Presented at Roulette in Brooklyn as part of this year’s Vision Festival, that rendition was slightly different from the recorded version. But the lyrical feeling of Smith’s motifs was also immediately identifiable.

In an interview, Vijayan said Smith was rarely prescriptive when handing out new directives before a concert. Instead, she said: “It was always from a place of emotional inspiration. ‘What is the feeling behind this tonight?’ And it could be different every night.”

That well-drilled flexibility allows the group to handle the Bartokian language of the first quartet as well as it handles the blues connotations of the third. Quartet No. 11, the 100-minute opus that takes up two discs in the boxed set, seems like a summation of the players’ ability to absorb everything Smith can throw at them.

The second movement, dedicated to Louis Armstrong, is a three-page, multicolored Ankhrasmation score. It omits a traditional staff, but features repeating structures. Its final page indicates a chord in a low string range. Bracketed instructions specify that this chord be played six times, before a pause. Then four times (with another rest after). And finally five more times. It makes for a dramatic, arresting climax.

The next movement, dedicated to Smith’s mother, is more traditionally notated — and offers the riddling complexity that Smith builds from motivic repetition.

Smith’s sound is all over these performances. And his trumpet joins the mix for String Quartet No. 6 (one of four in the set that features guest players). There, RedKoral responds to the trumpet’s virtuosic shifts of instrumental color and dynamics with intimate, collaborative intelligence.

“My playing of the trumpet — my drawings and construction of Ankhrasmation pieces — all of that goes into the expression of who I am,” Smith said. “All of my works express precisely who I am.”