This was supposed to be the year the Grammy Awards got back to normal. In 2021, the pandemic delayed the ceremony by six weeks and led organizers to put on a stripped-down outdoor show with no audience, which charmed critics with its intimate look yet had anemic ratings.

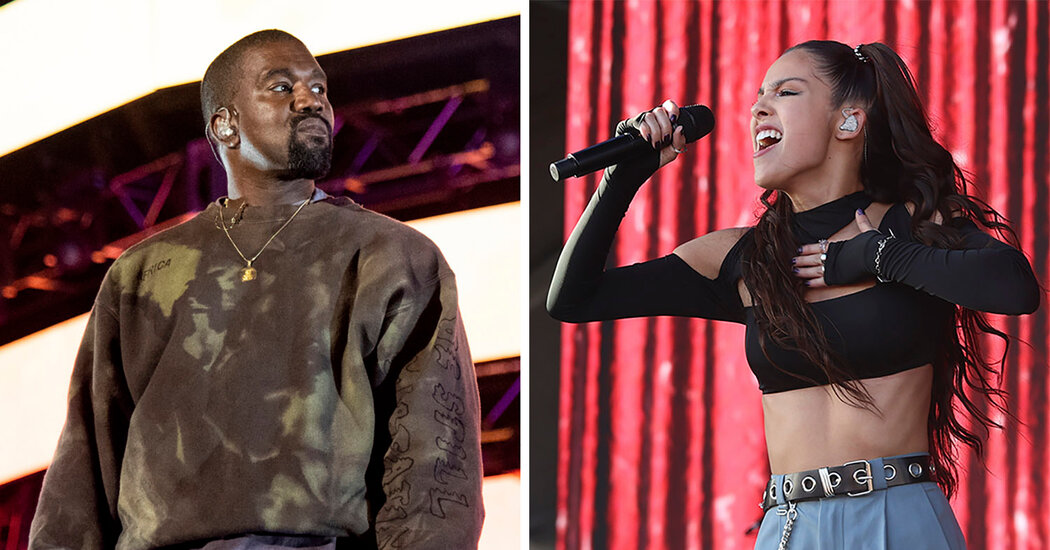

This year, after another delay — this one caused by the Omicron variant — the 64th annual Grammys have decamped for the first time to Las Vegas and will be broadcast by CBS on Sunday night from the MGM Grand Garden Arena. But a deluge of additional complications have followed. Kanye West was barred from performing because of his unsettling online behavior. Taylor Hawkins of Foo Fighters, who were scheduled to perform at the ceremony, died while on tour.

And then, at the Oscars on Sunday, Will Smith smacked Chris Rock onstage, an incident that grabbed headlines around the world and brought new scrutiny over how the organizers of major awards shows should handle star-on-star altercations on live television.

Even with those surprises — and after years of controversies at the Recording Academy, the nonprofit organization behind the Grammys — producers say they are ready for anything, and have worked to create a fresh look for the show. The ceremony will once again have an arena audience and feature full-scale performances by stars like Olivia Rodrigo, Silk Sonic, Billie Eilish, J Balvin, Carrie Underwood, John Legend and Lil Nas X. Other highlights include a tribute to Stephen Sondheim and a moment of observation of the war in Ukraine. Trevor Noah returns as the host.

The most closely watched contest is whether Rodrigo, the 19-year-old singer and actress whose song “Drivers License” was a sensation last year, can sweep the four top awards of album, record and song of the year, and best new artist. Her competition ranges from the meme master Lil Nas X to the 95-year-old Tony Bennett, who is up for “Love for Sale,” a Cole Porter album with Lady Gaga. The top nominee this year is Jon Batiste of “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert,” who has 11 nods.

Last year Ben Winston, who took over as the Grammys’ producer after a four-decade run by Ken Ehrlich, won plaudits for new touches like in-the-round performances and video segments building out the back stories of the nominees for record of the year, which has quietly replaced album of the year as the Grammys’ most coveted award.

A Guide to the 2022 Grammy Awards

The ceremony, originally scheduled for Jan. 31, was postponed for a second year in a row due to Covid and is now scheduled for April 3.

Some of those production decisions were necessities of pandemic-era television. But in an interview Winston said that even in an arena setting he wanted to keep a sense of last year’s intimacy and storytelling. The show on Sunday will highlight behind-the-scenes workers in the revived concert industry, and nominees from some of the dozens of Grammy categories rarely seen on television will be showcased on the roof of the MGM Grand. (Of the 86 awards, all but eight or nine are given out during a rapid-fire ceremony earlier that day.)

“I hope that the lessons we learned last year,” Winston said, “of trying to construct a TV show that touched on themes and wasn’t just a concert of one song followed by another, will stay for this year as well.”

Raj Kapoor, the showrunner this year, said that even the position of the stage — it has been lowered by about three feet — will foster a closer connection to the audience. (Kapoor is an executive producer of the show, along with Winston and Jesse Collins.) Still, some Covid measures will be evident to viewers. Nominated artists will be separated in a bistro-style seating area, and the number of people who will accept awards at the microphone will be reduced.

Just days before the show, uncertainties remain about who will perform, and even which stars might attend. Since Hawkins’s death on March 25, producers have raced to put together a tribute to the drummer. Two members of the K-pop group BTS recently tested positive for Covid-19, raising the question of whether or how the group would go through with its scheduled appearance.

The Recording Academy had no comment about BTS, and representatives of the group did not respond to questions about its plans. Foo Fighters, nominated for three awards, canceled their scheduled performance.

The biggest wild card may be West, whose invitation to perform was revoked after a barrage of troubling online behavior directed at his former wife, Kim Kardashian, and at Noah. But West is still up for five awards, including album of the year, for “Donda.” A representative of the Recording Academy said that after the episode at the Oscars, there are “plans in place for a variety of scenarios.”

For the academy, a smooth ceremony is especially important after years of complaints from artists and industry insiders about the awards process and the academy’s own governance. Stars like West, Drake, the Weeknd and Diddy, have criticized the Grammys over its poor record of rewarding Black artists in the top categories, and its opaque voting procedures.

The academy has taken steps to address those issues, but it remains to be seen whether that will be enough to quell dissent. Last year, it eliminated its longtime use of anonymous screening committees to determine many nominees, which the Weeknd and others had called unfair. Yet just one day before this year’s slate was announced in November, the academy’s rules were changed to add two spots to the ballot in the top four categories, allowing stars like West, Taylor Swift and Lil Nas X to gain nominations. Days after, Drake withdrew from competition in the two rap categories in which he was nominated, though he gave no explanation.

Harvey Mason Jr., the academy’s chief executive, said in an interview that the academy was working to regain confidence among its members. “My hope,” he said, “is that we will earn the trust of all that were mistrustful.”

So far, the music world seems willing to give the academy the benefit of the doubt.

“The issue with institutions like the Grammys is that there is always a sense of nostalgia and tradition, so change is generally a little slower,” said Ghazi, the founder of the independent music company Empire. “But some of the conversations we have been having have been encouraging.”

Willie Stiggers, known as Prophet, an artist manager and co-chair of the Black Music Action Coalition, said he takes Grammy leaders at their word about a commitment to foster diversity within the organization. “The Recording Academy is a reflection of American society,” he said. “It’s going to take more than a year or two to unpack all that.”

One area in which the Grammys, and the music industry as a whole, have shown a stubborn lack of progress is in the advancement of female creators. This week, the latest edition of an annual study by the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at the University of Southern California found that credits for women in pop have essentially remained flat over the past decade. Last year just 23.3 percent of the credited artists among the top 100 songs were women, while a Grammy-sponsored pledge from 2019 to hire more female producers and engineers has had almost no impact, the study found.

“Despite industry activism and advocacy, there has been little change for women on the popular charts since 2012,” Stacy L. Smith, one of the study’s authors, said in a statement.

A larger debate in the music industry looms over the value of the Grammys — and of all awards shows — in an era of fragmented viewing and declining ratings. Last year the Grammys drew just 8.8 million viewers, its worst showing ever, and the sales benefits that artists and record companies used to enjoy from a prominent Grammy appearance have nearly vanished.

According to Will Page, an economist who studies the music industry, the two-week sales gain after Adele won album of the year in 2012, for “21,” was worth $1 million in estimated artist royalties, while Swift’s win last year, for “Folklore,” brought her just $50,000. “Today’s harsh reality is that winning over the judges doesn’t necessarily win over the consumers,” Page said.

For the producers of the TV show, however, the imperative is to keep the event feeling fresh. And they say they are up to it.

“Things can get stale,” Winston said, “if they stay the same.”