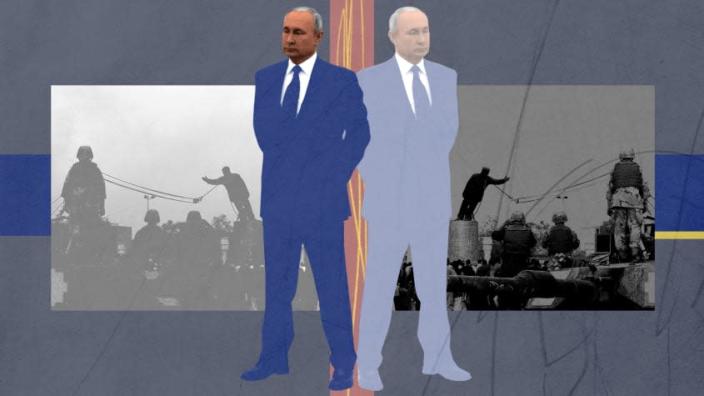

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine has disillusioned many of the hope of a new era, a time free of great wars, on autopilot toward liberalization. But war is a fact of nature. Peace, on the other hand, is a human product, and it takes superpower to preserve it. At the end of the Cold War, a segment of foreign policy experts and intellectuals on the right were warning that the allure of peace was too dangerous, that the post-Cold War era was a moment that could not last forever. This cohort was closely associated with the Reagan administration. Indeed, many of them worked for the man who won the Cold War. They would go on to be labeled neoconservatives.

In 1996, two Reagan alumni, Bill Kristol and Robert Kagan, wrote an essay that prescribed what the foreign policy of the United States should look like: protecting U.S. hegemony and military superiority; maximizing U.S. power; engagement with the world; and promoting liberal democracy. That vision came to define the movement.

The whole story was bigger, of course. Irving Kristol, regarded as the godfather of neoconservatism, was mainly interested in domestic policy, and his preferences for foreign policy didn’t always overlap with the foreign policy neoconservatives who would come later. But for whatever reason, the label stuck. Throughout the 1990s, these neo-Reaganites were the respected scholars and experts of the right. They were the smart and educated Republicans.

The 2000s changed that. The global war on terror made U.S. interventionism and promotion of freedom around the world unpopular at home and abroad. For many progressives, conservatives, and libertarians, “neocon” became a slur, usually with anti-Jewish connotation. It meant bagel-eating warmongers. Columnist David Brooks wrote that “con [was] short for ‘conservative’ and neo [was] short for ‘Jewish.'”

Most of the “cabal,” as one anti-Jewish writer referred to them, rejected the neocon title. But the title mattered less than the ideas, and those had become unpopular. In every presidential race since 2008, the hawkish nominee lost to a more dovish alternative, including in 2016, when a comparatively dovish Donald Trump, recycling the isolationist “America First” slogan associated with Nazi sympathizers of the 1930s and 1940s, beat Hillary Clinton.

As the Obama-Trump era was waning, however, elements of the neoconservative agenda began to make a comeback. President Biden’s foreign policy platform called for repairing America’s alliances, promoting American values, and leading the world. The only missing ingredient to make the platform neoconservative was building a large military and a lower threshold for using it. Indeed, many of those often labeled as neoconservatives endorsed and voted for Biden, in no small part due to his promise to restore America’s standing in the world.

And if Biden’s platform matched the views of the mean American voter in 2020, after a year in office, he’s behind the times. After the invasion of Ukraine, Americans want a more active, interventionist foreign policy. But it is not Biden who has changed — it’s the world. Americans are simply waking up to reality.

It’s not such a shift as those recent presidential races might suggest. Neoconservative foreign policy is well within the mainstream of American political thought and culture. Polls have consistently shown Americans like having a strong military, support promoting liberalism abroad, and like to trade with other nations. They hate tyrants and don’t mind punishing human rights abusers and supporting freedom activists. Surveys also show Americans’ support for their allies has always been strong. The only stinging issue is the use of force, about which Americans change their minds often and quickly.

But there are two ways neoconservatism is unique as an approach to foreign policy, and they make it particularly apt for this moment: an assertive cynicism and an assertive hope.

The cynicism applies to dictators. No tyrant is benign, and powerful ones can be very dangerous. It is especially dangerous to believe in an ideologically driven tyrant’s capacity to keep the peace. When they tell the world they’re evil, it is sound judgment to believe them.

The hope goes to the oppressed peoples of the world. The universality of human nature — the equal dignity of us all that is the key principle of the American project — means that, freed from the shackles of oppression, all nations could live freely, peacefully, and prosperously. But they need American help to free themselves.

Putin’s war vindicates that cynicism. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and his nation’s courageous resistance (as well as anti-war protesters in Russia risking arrest and persecution) vindicate the neoconservative hope. But only America can operationalize those views.

That’s what sets apart a neoconservative or neo-Reaganite stance from that of a traditional conservative. “America’s strength lies as much in its conception and realization of the concept of ordered liberty as in its economic and military strength,” Elliott Abrams, one of the sages of national security Republicans and alumnus of three Republican administrations, told me over email. “[N]eocons are more inclined to support human rights policy than other conservatives and to support what might be called a more idealistic foreign policy.”

Idealism and strength are especially needful now, as enemies of freedom once again demonstrate to the free world that we can’t take our way of life for granted. China has demonstrated that in Hong Kong and threatens to do the same in Taiwan. Iran has been terrorizing the greater Middle East through its proxies, and its nuclear weapons program will multiply the travesty by many orders of magnitude. But these pale in comparison to what Russia has undertaken over the past month.

Polls show an overwhelming majority of Americans want to punish Putin and support Ukraine. Similar numbers support American efforts to stop Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons, and a majority are in favor of defending Taiwan against China. Americans want to support fights against tyranny, and only America — with its exceptional heritage, extraordinary power, and anomalous role in history — can effectively be the world’s safeguard of freedom.

If we’d forgotten that before Putin invaded Ukraine, we should remember it now.

You may also like

Ted Cruz checked his Twitter mentions and a little bit of our democracy died

Dick Durbin thanks Ben Sasse for ‘jackassery’ remarks: ‘There was great truth in what he said’