WASHINGTON — In his record-breaking run as prime minister, Shinzo Abe never achieved his goal of revising Japan’s Constitution to transform his country into what the Japanese call a “normal nation,” able to employ its military to back up its national interests like any other.

Nor did he restore Japan’s technological edge and economic prowess to the fearsome levels of the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Japan was regarded as China is today — as the world’s No. 2 economy that, with organization and cunning and central planning, could soon be No. 1.

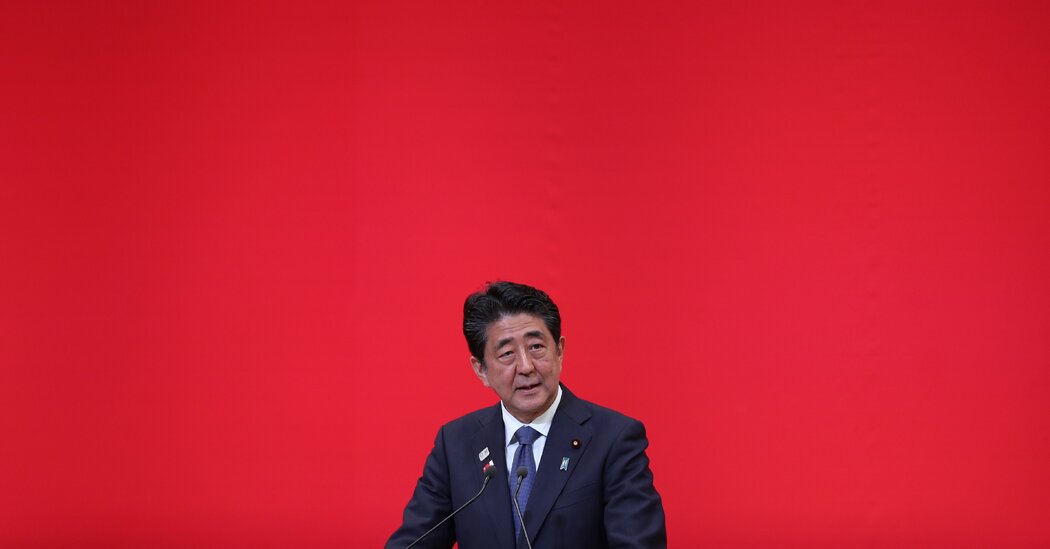

But his assassination in the city of Nara on Friday was a reminder that he managed, nonetheless, to become perhaps the most transformational politician in Japan’s post-World War II history, even as he spoke in the maddeningly bland terms that Japanese politicians regard as a survival skill.

After failing to resolve longstanding disputes with Russia and China, he edged the country closer to the United States and most of its Pacific allies (except South Korea, where old animosities ruled).

He created Japan’s first national security council and reinterpreted — almost by fiat — the constitutional restrictions he could not rewrite, so that for the first time Japan was committed to the “collective defense” of its allies. He spent more on defense than most Japanese politicians thought wise.

“We didn’t know what we were going to get when Abe came to office with this hard nationalist reputation,” said Richard Samuels, the director of the Center for International Studies at M.I.T. and the author of books on Japan’s military and intelligence capabilities. “What we got was a pragmatic realist who understood the limits of Japan’s power, and who knew it wasn’t going to be able to balance China’s rise on its own. So he designed a new system.”

Mr. Abe was out of office by the time Russia invaded Ukraine this year. But his influence was still evident as Japan, after 10 weeks of hesitation, declared it would phase out Russian coal and oil imports. Mr. Abe pushed further, suggesting that it was time for Japan to establish some kind of nuclear sharing agreement with the United States — breaking his country’s longtime taboo on even discussing the wisdom of possessing an arsenal of its own.

His efforts to loosen the restraints on Japan that date back to its postwar, American-written Constitution reflected a recognition that Japan needed its allies more than ever. But alliances meant that defense commitments went both ways. China loomed larger, North Korea kept lobbing missiles across the Sea of Japan and Mr. Abe believed that he needed to preserve his country’s relationship with Washington, even if that meant delivering a gold-plated golf club to Donald J. Trump at Trump Tower days after he was elected president.

Mr. Abe was not killed for his hard-line views, which at moments triggered street protests and peace rallies in Japan, at least according to initial assessments. Nor was his killing a return to the era of “Government by Assassination,” the title that Hugh Byas, the New York Times bureau chief in Tokyo in the 1930s, gave his memoir of an era of turmoil.

Mr. Byas recounted the last killing of a current or former Japanese prime minister: Tsuyoshi Inukai was killed in 1932 as part of a plot by Imperial Japanese Navy officers that seemed intended to provoke a war with the United States nine years before Pearl Harbor.

In the postwar era, political assassinations have been rare in Japan: a Socialist leader was murdered in 1960 with a sword, and the mayor of Nagasaki was shot dead in 2007, though that appeared to be over a personal dispute. And the American ambassador to Japan in the 1960s, Edwin O. Reischauer, was stabbed in the thigh by a 19-year-old Japanese man; Mr. Reischauer survived and returned to his post as Harvard’s leading scholar of Japanese politics.

Mr. Abe’s death will now set off a race to be the next leader of one of the most powerful factions of the Liberal Democratic Party. And the shock of it, President Biden said on Friday during a visit to the C.I.A., will have “a profound impact on the psyche of the Japanese people.”

But it will hardly create a political earthquake. Mr. Abe left office, partly because of poor health, two years ago. And in the pantheon of current world leaders, he could not match the powers of Presidents Xi Jinping of China or Vladimir V. Putin of Russia; Japan’s humbling recession in the 1990s damaged its ranking as a superpower.

But his influence, scholars say, will be lasting. “What Abe did was transform the national security state in Japan,” said Michael J. Green, a former senior official in the George W. Bush administration who dealt with Mr. Abe often. Mr. Green’s book “Line of Advantage: Japan’s Grand Strategy in the Era of Abe Shinzo” argues that it was Mr. Abe who helped push the West to counter China’s increasingly aggressive actions in Asia.

“He was chosen for the prime ministership because of a sense in Japan that they were being humiliated by China at every turn,” Mr. Green said. It was Mr. Abe who pressed for the emergence of the Quad, a strategic security coalition of four nations — Australia, India, Japan and the United States — that Mr. Biden has now embraced.

Mr. Abe was, of course, not above crude political tactics to get his way. He believed Japan had apologized enough for its war crimes, and he visited the Yasukuni Shrine, a memorial that honors Japan’s war dead — including war criminals — in 2013.

Mr. Abe’s grandfather, who was accused of war crimes before he became prime minister in the late 1950s, is among those commemorated at Yasukuni. Mr. Abe’s father was a conservative foreign minister and the minister of international trade and industry, which ran Japan’s industrial policy.

In 2012, as Mr. Abe returned to the prime minister’s office, President Barack Obama’s aides worried he was too hawkish, but over time they warmed to him. Mr. Obama and Mr. Abe traveled to Hiroshima to lay a wreath at the site where the United States dropped the first atomic bomb, a politically risky appearance for both men.

When Mr. Trump was elected, Mr. Abe pivoted. In addition to showing up at Trump Tower with a gold-plated golf club, he traveled to Mar-a-Lago to celebrate the birthday of Melania Trump, the first lady. He sat and tolerated it when Mr. Trump threatened to pull back American troops from Japan because the country ran a trade surplus with the United States. Mr. Abe smiled benignly through it all, as if he were waiting for a storm to pass.

Mr. Abe staked his political future on a trade agreement called the Trans-Pacific Partnership. When Mr. Trump rejected it, the prime minister continued to nurture the 2016 agreement, almost ignoring the fact that Washington was missing. Japan ratified it in 2017; the United States never has.

The Japanese leader viewed managing a mercurial American president as just one more part of the job of a lesser but high-tech power, understanding that for all the billions he had added to Japan’s defense budget, he was still highly dependent on Washington.

“We have no choice,” Mr. Abe told a reporter stopping in at his office at the prime minister’s residence in 2017, acknowledging that Mr. Trump was forever threatening to pull all American troops out of Japan, with little interest in discussing why they were there to begin with.

Mr. Abe seemed to know, as Mr. Samuels put it, that “both Japan and the United States are in relative decline” and thus must combine their talents and resources.

“This is a relationship that must work,” Mr. Abe concluded.