WASHINGTON (AP) — The Senate whisked a $40 billion package of military, economic and food aid for Ukraine and U.S. allies to final congressional approval Thursday, putting a bipartisan stamp on America’s biggest commitment yet to turning Russia’s invasion into a painful quagmire for Moscow.

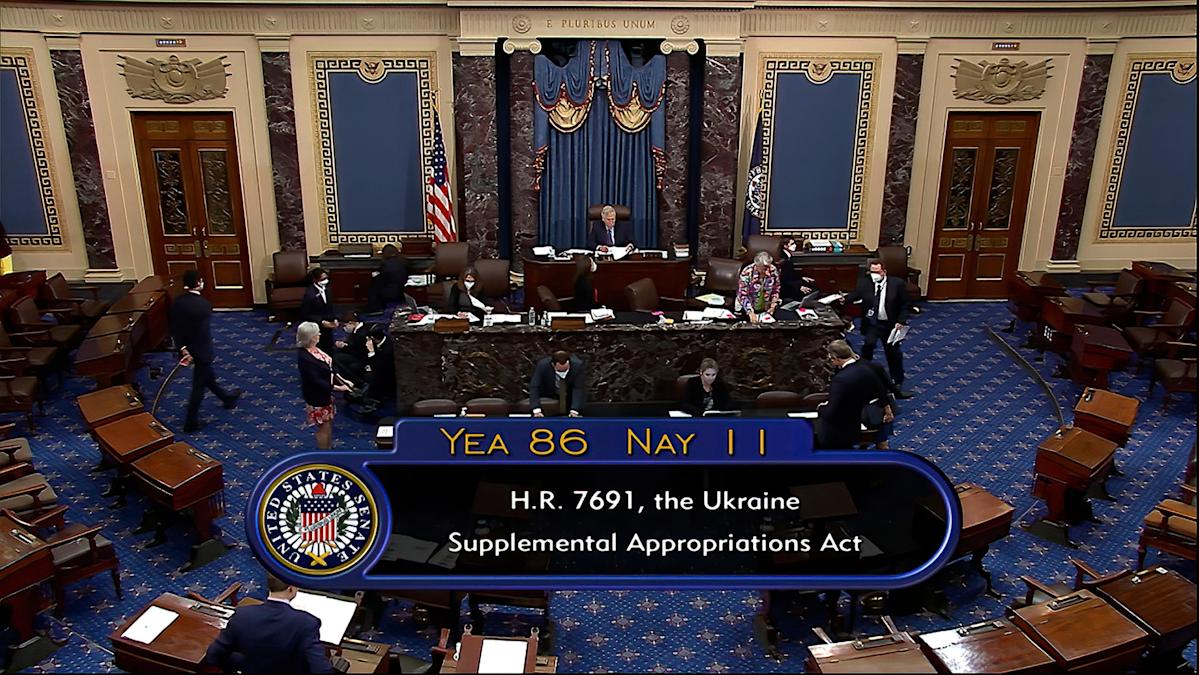

The legislation, approved 86-11, was backed by every voting Democrat and most Republicans. While many issues under President Joe Biden have collapsed under party-line gridlock, Thursday’s lopsided vote signaled that both parties were largely unified about sending Ukraine the materiel it needs to fend off Russian President Vladimir Putin’s more numerous forces.

“I applaud the Congress for sending a clear bipartisan message to the world that the people of the United States stand together with the brave people of Ukraine as they defend their democracy and freedom,” Biden said in a written statement.

With control of Congress at stake in elections less than six months off, all “no” votes came from Republicans. The same thing happened in last week’s 368-57 House vote, fueling campaign-season Democratic warnings that a nationalist wing of the GOP was in the thrall of former President Donald Trump and his isolationist, America First preferences.

Trump, who still wields clout in the party, has accused Biden of throwing money at Ukraine while mothers lack baby formula, a crisis sparked by a supply chain problem over which the government has scant impact.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., called it “beyond troubling” that Republicans were opposing the Ukraine assistance. “It appears more and more that MAGA Republicans are on the same soft-on-Putin playbook that we saw used by former President Trump,” said Schumer, using the Make America Great Again acronym Democrats are using to cast Republicans as extremists.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., a strong backer of the measure, warned his GOP colleagues that a Russian victory would move hostile forces ever closer to the borders of crucial European trading partners. That would prompt higher American defense spending and tempt China and other countries with territorial ambitions to test U.S. resolve, he said.

“The most expensive and painful thing America could possibly do in the long run would be to stop investing in sovereignty, stability and deterrence before it’s too late,” McConnell said.

Passage came as Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the U.S. had drawn down another $100 million worth of Pentagon weapons and equipment to ship to Kyiv, bringing total U.S. materiel sent there since the invasion began to $3.9 billion. He and other administration officials had warned that authority would be depleted by Thursday, but the new legislation will replenish the amount available by more than $8 billion.

Overall, around $24 billion in the measure is for arming and equipping Ukrainian forces, helping them finance weapons purchases, replacing U.S. equipment dispatched to the theater and paying for American troops deployed in nearby countries.

There is also $9 billion to keep Ukraine’s government afloat and $5 billion to feed countries around the globe reliant on Ukraine’s now diminished crop yields. And there is money to help Ukrainian refugees in the U.S., seize Russian oligarchs’ assets, reopen the U.S. embassy in Kyiv and prosecute Russian war crimes.

The measure, which officials have said is designed to last through September, tripled the size of the initial $13.6 billion in Ukraine aid that lawmakers approved shortly after the February invasion.

The combined $54 billion price tag exceeds what the U.S. has spent annually on all its military and economic foreign assistance in recent years, and approaches Russia’s yearly military budget.

“Help is on the way, really significant help. Help that could make sure that the Ukrainians are victorious,” said Schumer, voicing a goal that seemed nearly unthinkable when Russia first launched its brutal attack.

If the war drags on, as seems plausible, the U.S. may have to eventually decide whether to spend more even as inflation, huge federal deficits and a potential recession loom. Under those circumstances, winning bipartisan approval of any future aid bill could become tougher, especially as November draws near and cooperation between the parties frays.

Several potential 2024 GOP presidential contenders voted for the measure, including Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas, Tom Cotton of Arkansas and Marco Rubio of Florida. Another — Josh Hawley of Missouri — voted no. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, who perhaps face this fall’s toughest reelection races among GOP senators, backed the measure.

Three Democratic senators missed the vote. Chris Van Hollen of Maryland is recovering from what he’s called a minor stroke. Sherrod Brown of Ohio’s office said he woke up “not feeling well,” took precautionary tests at George Washington University Hospital, was resting at home and plans to return to the Capitol next week. Jacky Rosen of Nevada’s office said she was attending her daughter’s law school graduation.

Biden had proposed a $33 billion plan that lawmakers bolstered with added defense and humanitarian spending. He had to drop his request to include $22.5 billion more to fuel the government’s continued fight against the pandemic, spending that was opposed by many Republicans and got entwined in a politically complicating fight over immigration.

No Republican opposed to the legislation spoke during Thursday’s debate. After passage, Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., among the 11 conservatives who voted “no,” questioned whether voters would support the bill if Congress asked them to pay for it.

“I wonder if Americans across our country would agree if they had been shown the costs, if they had been asked to pay for it,” said Paul. “We simply borrow it. ‘Put it on my tab’ is what Congress says.”

Paul, who often opposes U.S. intervention and makes a habit of derailing bills on the brink of approval, had used Senate procedures to upend Schumer’s and McConnell’s plans to approve the Ukraine assistance last week.