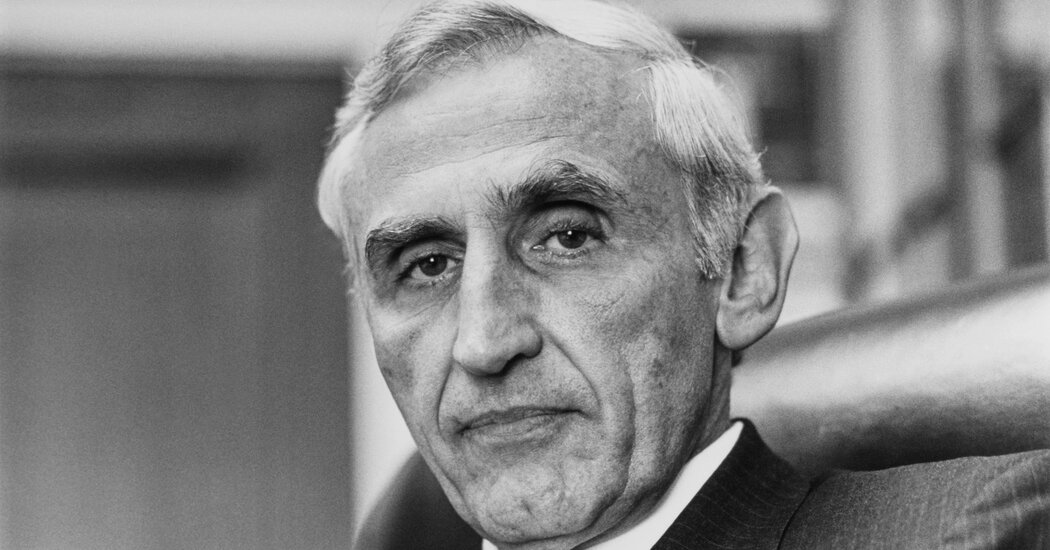

Romano L. Mazzoli, the son of an Italian immigrant who as a Democratic representative from Kentucky teamed up with a conservative senator from Wyoming to champion the last major attempt at comprehensive immigration reform, died on Tuesday at his home in Louisville, Ky. He was 89.

Charlie Mattingly, his former chief of staff, confirmed the death.

Mr. Mazzoli was a five-term backbencher in the House of Representatives in 1980 when he took over as chairman of the Subcommittee on Immigration, Refugees and International Law after his predecessor, Elizabeth Holtzman of New York, left the House for a Senate run that proved unsuccessful.

He then reached across the Capitol — and across the aisle — to his counterpart in the Senate, Alan K. Simpson, about making fundamental changes to the creaking U.S. immigration system. More than three million undocumented immigrants lived in the country at the time, thanks in part to poor enforcement.

Both politicians had personal motivations.

Mr. Mazzoli’s father, also named Romano, had moved to Louisville from a small town in northern Italy. And Mr. Simpson, as a child, had seen the animus aimed at the children of nonwhite immigrants when he befriended a Japanese American boy — and a future congressional colleague — named Norman Y. Mineta, who had been sent to a Wyoming internment camp during World War II.

Mr. Mazzoli and Mr. Simpson developed a grand compromise: amnesty for millions of immigrants combined with penalties for employers and other forms of enforcement to reduce future inflows.

What followed was one of the longest legislative sagas in recent congressional history — a “roller coaster odyssey,” Mr. Mazzoli called it. The Senate proved relatively amenable to the bill, but its House version, which had enemies on both sides, failed repeatedly. Pundits and politicians wrote its eulogy many times over, often with relief or even glee.

In 1984, Alan Cranston of California, a member of the Democratic leadership, declared it a “bad bill.” He told reporters: “It’s beginning to look like the Simpson-Mazzoli bill is dead for this session of Congress at least, and that is very, very good news. The sooner it is buried and forgotten, the better.”

Yet the bill refused to die. Mr. Mazzoli finally got the House version passed, after spending a lonely few days bouncing around the chamber floor rallying allies.

“I used to be 6-foot-7 until they kept pounding me down,” he told The New York Times in 1984. “Then I became 5-foot-9.”

But even that wasn’t enough. The two chambers failed to reconcile their versions in conference, and the bill died once again.

It finally passed in 1986, with significant alterations in the details but still in keeping with the original Simpson-Mazzoli framework. President Ronald Reagan signed it that fall, with Mr. Mazzoli looking on.

The legislation, called the Immigration Reform and Control Act, was the last successful effort to change the country’s immigration laws. But its flaws emerged almost immediately.

Mr. Mazzoli was among its earliest critics, pointing out that the Immigration and Naturalization Service was underfunded and appeared not to have made the law’s enforcement aspect a priority. In addition, fraud was rampant, and illegal immigration surged.

Still, the bill stands as a landmark of bipartisan compromise, the sort that later generations of legislators could only dream of.

“I’m going to carve a very modest role around this place,” Mr. Mazzoli told The Times. “But I wanted to prove to the country and to the leadership that we could deal with an emotionally laden and divisive subject in a way that brought credit to the House.”

Romano Louis Mazzoli was born on Nov. 2, 1932, in Louisville. His father, a tile layer with his own business, had arrived in the city as a boy from Maniago, a small city in northern Italy. His mother, Mary (Iopollo) Mazzoli, who was born in Cleveland, kept her husband’s books.

He majored in business at the University of Notre Dame, intending to return to Louisville and work for his father. But after graduating in 1954, he was drafted into the Army, where he was assigned to keep minutes during administrative and legal hearings in Alaska. That experience persuaded him to become a lawyer.

He graduated first in his class from the University of Louisville School of Law, then worked for the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and in private practice.

He married Helen Dillon in 1958. She died in 2012. He is survived by his son, Michael; his daughter, Andrea Doyle; and four grandchildren.

By the late 1960s Mr. Mazzoli was growing bored with the low-level legal work he was being assigned. One day in 1966 he wandered into the local Democratic Party headquarters, and within a few weeks he was a candidate for State Senate.

He won that race. In 1969 he ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Louisville. In 1970 he ran for Congress and defeated the Republican incumbent, William Cowger, by just 211 votes.

He was also a critic of the surge of money into House races. He refused to take money from political action committees or any donation over $100. He decided not to run for re-election in 1994 in large part because he was tired of the constant fund-raising.

Mr. Mazzoli then returned to private practice. He also taught classes at the University of Louisville and Bellarmine University, a Roman Catholic institution in Louisville.

After spending time as a fellow at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University in 2002, he returned to the Harvard Kennedy School the next year as a full-time master’s student. He and his wife lived in a dorm, ate in the dining hall and made friends with undergraduates.

Among them was Pete Buttigieg. The two graduated together in 2004 and remained close friends. When Mr. Buttigieg became mayor of South Bend, Ind., in 2012, Mr. Mazzoli officiated the swearing-in ceremony.