Much of the recent coverage and debate about immigration concerns those who travel to the UK via the Channel, and especially how much it costs to keep people housed once they arrive.

There is another cost, however, and that is to the mental health of those who have suffered severe trauma in the process of travelling to the UK, according members of Bristol’s largest growing migrant community.

More than 40,000 people crossed the Channel in small boats in 2022 alone.

In a series of exclusive interviews for BBC News, members of the Somali community in Bristol share the impact of their treacherous journeys to safety.

.

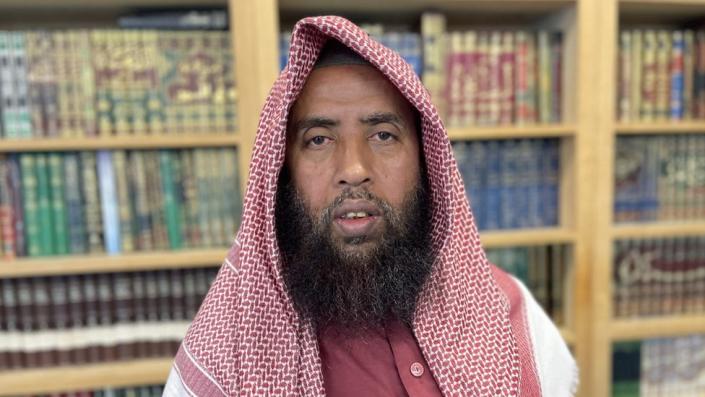

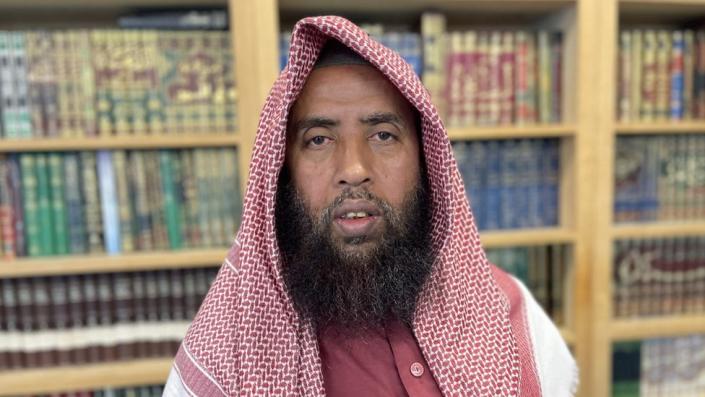

Abdirahman Jama, head of Albaseera Mosque in Bristol, is calling for support with mental health diagnoses caused by immigration trauma.

Mr Jama meets people with mental health needs on a “daily basis”.

He said many who have made the journey in some of the “worst” situations come to the mosque for help.

“A lot of people have come through what we call ‘hell’,” he said.

“They cross the desert, they see their friends dying in the desert, some women raped on the way, some who have been tortured.

“When they come here, what they were expecting is different to what they got here.

“After all they have gone through they were expecting they would get rest, change their lives and get a better life.

“But the system makes them wait for a long time – the legal system and the financial system.

“When they get help it’s too late.”

Mr Jama has called for more training and help for mosque leaders to support those fleeing trauma.

‘Die piece by piece’

Samira (not her real name) told the BBC how she fled her home in Somalia and walked between the borders of Eritrea and Sudan before making the journey through the Sahara desert and then across the sea – all at the age of 20.

She was one of just 15 out of 100 people making the journey who survived to reach the UK.

She said: “On this journey, you don’t die once, you die piece by piece and at the end when you’ve survived, your mental health is damaged.

“For two months we were held captive under smugglers.

“A car came and he took 26 people and they all died. People were all fighting to get on the car.

“Another car came and I went in. The drivers had guns and knives.

“I was the only survivor.

“You don’t know where you’re going, where they’re taking you and whether you’re going to die or live.”

Samira boarded a small boat which then sank and she was saved by the Italian Army.

Istahil Ahmed is calling for the government to implement a “safer” process to help families and couples to reunite.

Her daughter Amal Abdi was murdered by her son-in-law Abdirashid Khadar in Bristol in 2015 after he travelled to the UK illegally.

She believes the trauma of the journey “desensitised” him.

Mrs Ahmed said: “[Abdi] saw people dying – people who died who were thrown off the boat and into the sea.

“He saw people who were hungry in a deserted place ending up eating flesh.

“When they entered Libya, he was held captive for a long time underground, his throat was slit.

“So, when he saw all that he became desensitised.

“He doesn’t see killing as anything important so it became easy for him to kill my daughter.”

‘Seek protection’

Prof Cornelius Katona, a psychiatrist who has been specialising in the mental health of asylum seekers and refugees for the past 20 years, said the level of trauma experienced by refugees is likely to be “considerably greater” than that suffered by other migrants.

He said: “Leaving your country can be traumatic. It can be traumatic because it means that you lose contact with family, you lose contact with friends, you lose the social network you had.

“But for people who escape or people who leave their country because they feel unsafe they feel they need to seek protection elsewhere.

“That separation and the trauma around it can be much more profound.”

He added that having safe and legal routes available would make the journeys less hazardous and traumatic.

He also said the sooner people have the treatment they need the better.

“Both refugees and people who are in the process of seeking asylum are entitled to full NHS care but they may not be aware of that,” he said.

“They may think they will subsequently have to pay for services.”

According to Prof Katona, not everyone who is traumatised becomes mentally ill, however, nightmares, flashback experiences and seeing or hearing elements of past trauma are suggestive of possible post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

“The main thing that people tend to avoid is things that remind them of their trauma.

“If they are reminded of their trauma that is likely to trigger those re-experiencing things like nightmares and flashbacks and intrusive thoughts so they’re reluctant to talk about it, and that may mean that they don’t disclose what happened to them.

“They may also feel that anything that suggests that they have a mental illness may be stigmatising.

“These are not things that people do for fun. They do it because it’s the only way they can get to the UK.

“Making people welcome is likely to enable them to integrate more effectively.” He added.

Rates of PTSD are higher in survivors of human trafficking and refugees than in migrants who are not forcibly displaced, according to research on Gov.UK.

In a study of survivors of human trafficking, 78% of women and 40% of men screened were suffering from anxiety, depression or PTSD.

Khadra Siyad was six months’ pregnant when she arrived in the UK in April 2014, seeking a better life for her children.

She sought asylum and waited for seven years for her legal documents to be processed, with no financial support.

She said: “I waited without a single penny, unable to work with no bank card, no income, no one to talk to.

“I had three children, the problems got worse and I was becoming increasingly unwell.

“I needed help. Whenever I asked family for advice they told me not to speak to anyone otherwise I will have my children taken away by social services.”

One night, Ms Siyad made the “life-changing decision” to go to her local GP directly to get help.

“I went to Wellspring Surgery and told the doctor all my problems,” she said.

“There was no reason for my children to be taken away simply for wanting help.”

Within a year, Ms Siyad received help with obtaining her legal documents and, due to her three children being British, she was granted her British citizenship.

She was able to get a job and bring five of her six children in Somalia to the UK.

Reunited, she now lives in a two-bedroom flat with eight of her children.

“So many mothers have the same problems,” she added.

“I now know, so I tell them to leave their houses and go to see their GP to share all their problems.”

According to Zahra Kawsar, a mental health coordinator and registered social worker, trauma can come from war displacement and fleeing persecution.

With more than 10 years of experience in the mental health sector and as a survivor of war in Somalia, she highlighted the challenges for those trying to access support.

“There are language barriers, accessibility issues and not knowing the support available to them,” she said.

“Sometimes services are stretched and people have to wait for counselling for two years.

“It can be hard. Some people recover from it and for some people it takes them a long time time to recover from it.

“It’s not that people forget what happened but sometimes some people find a way to move on with life.”

The UK Government website has advice and guidance on the mental health needs of migrant patients for healthcare practitioners.

Religion-tailored advice and guidance is also available, as well as a section for vulnerable migrants living in the UK.

The Refugee Council,The Children’s Society Refugee Toolkit, The Bridges Programmes, Asylum Aid and Freedom from Torture are all resources that can be accessed.

If you have been affected by any of these issues, you can visit the BBC’s Action Line, or contact the Samaritans.

Follow BBC West on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: bristol@bbc.co.uk