A key factor that explains Vladimir Putin’s military invasion of Ukraine is traditional Russian imperialism.

Throughout the world’s long and bloody history, other powerful territories — and, later, nations — expanded their lands through imperial conquest, including Rome, China, Spain, France, Britain, Germany, Japan and the United States.

Russia was no exception. Beginning with the small principality of Moscow in 1300, Russia employed its military might to crush neighboring peoples and gobble up territory across the vast Eurasian continent. Under the czars, it became known as the “prison of nations.” By the early twentieth century, Imperial Russia was the largest country in the world ― and, also, one of the most brutal and reactionary.

When the Bolshevik Revolution occurred, part of its impetus was a revolt against the imperialist role of Russia and other great powers of the era. Vladimir Lenin denounced imperialism, loosened the Russian grip on some subject countries and promised that, within the Soviet Union, the new Soviet republics would have self-determination.

Unfortunately, with the rise of Joseph Stalin, that anti-imperialist impulse was abandoned. When it came to the Ukrainian People’s Republic, which had not fulfilled the grain production quota set by the Kremlin, Stalin, in 1932 and 1933, shipped off 50,000 Ukrainian farm families to Siberia and ordered the seizure of Ukraine’s grain crop. Massive starvation followed in Ukraine, causing an estimated 4 million deaths. Not surprisingly, this treatment did not endear Ukrainians to the Soviet regime.

NJ Congressman: Putin, his enablers and Russia must be punished — now

Mike Kelly: Joe Biden’s State of the Union was a plea to moderates. Was it too late?

Although most Russians ― and most Communists ― were horrified by the rise of Nazi Germany during the 1930s, Stalin signed a pact with Hitler (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) in August 1939. Its secret provisions turned over the independent nations of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, as well as the eastern half of Poland, to the USSR, which soon occupied them. It also provided a green light for the Soviet invasion of Finland (which led to Soviet seizure of a portion of that country) and Soviet seizure of a portion of Romania. As the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact also provided Soviet endorsement of Nazi Germany’s imperialist ambitions, Hitler promptly launched World War II.

In June 1941, however, things shifted dramatically, for Hitler, overly ambitious, began a full-scale military invasion of the Soviet Union, thereby double-crossing his ally. In the ensuing bloody conflict, the Russians fought fiercely against Germany for their very survival. They were aided by Britain and the United States, both of which also took on the powerful Japanese armed forces in the Pacific.

After World War II, although Ribbentrop was tried at Nuremberg and executed, Molotov and Stalin were not, for, of course, they were on the winning side of the war. As part of the spoils of victory, the Soviet Union incorporated Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and eastern Poland into its territory.

This proved only the beginning of a new round of Russian imperialism. In the aftermath of the war, the Soviet Union took control of most nations in Eastern Europe and retained them as vassals and unwilling partners in the Warsaw Pact. They included Poland, Hungary, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Albania, Bulgaria and East Germany. The Soviet Union retained its grip on them through Communist Party dictatorships that it imposed, occupations by Soviet troops, and military assaults, most notably bloody invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, where Communist regimes proved too independent for the tastes of the Kremlin. In Hungary, Soviet military repression produced 20,000 Hungarian casualties — including 2,500 deaths — and 200,000 refugees.

When the reform-minded Mikhail Gorbachev finally stopped enforcing Soviet imperial rule in Eastern Europe, revolutions in these countries swept aside the tired pro-Soviet dictatorships and reasserted their national sovereignty. Not surprisingly, many of these newly independent countries then began to apply to join NATO ― not because they were forced to do so, but because they feared a reassertion of Russian domination.

Events in Ukraine illustrate this desire for freedom from Russian control. Gorbachev allowed a referendum on Ukrainian independence to take place in 1991. In a turnout by 84% of registered voters, some 90% of them voted for independence from Russia. As part of its independence arrangement, Ukraine ― which had the third largest nuclear arsenal in the world ― handed over all its nuclear weapons to the Russian government. In turn, as part of the Budapest Memorandum of 1994, Russia formally pledged to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty.

But the Russian government began to backtrack on its agreement with Ukraine. It was happy with the rule of Viktor Yanukovych, a pliable pro-Russian politician. But when the political tide turned against him and he was ousted from office because he blocked Ukraine’s membership in the European Union, Russian leaders were incensed. Ukraine was turning toward the West, and this, they believed, could not be tolerated. In a clear violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty, the Russian government deployed its military power to seize Crimea and take control of Russian-language separatist regions in eastern Ukraine.

Of course, the Russian government sought to justify its actions with flimsy claims, then and subsequently. It said that there was no military intervention by Russia. But clearly there was. It said that there were fascists in Ukraine. True enough; but there were also plenty of fascists in Russia and in many other lands. Ukraine’s government, it said, was under the control of an unrepresentative Nazi cabal. But Zelensky was elected with 73% of the vote, remains wildly popular and is certainly no right-winger or authoritarian. Can we say the same about Vladimir Putin?

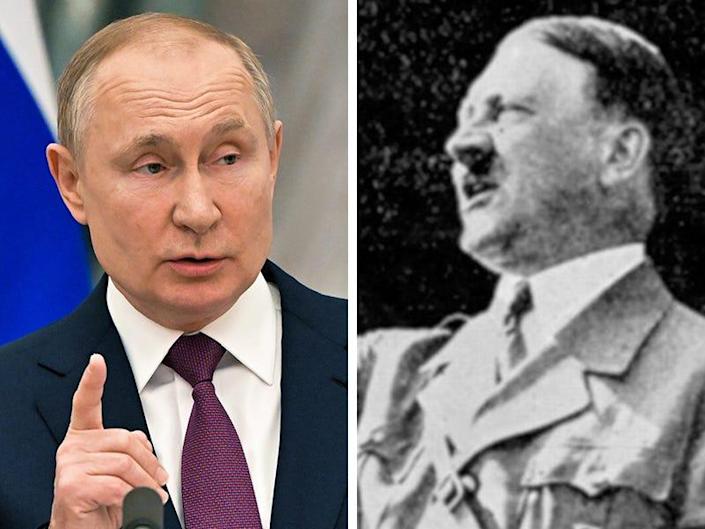

When one looks at what Putin has declared in his recent pronouncements, his dominant motive is clear enough. Denying that Ukraine has any right to statehood independent of Russia and glorifying the expansionism of his country’s Czarist and Stalinist past, he is caught up in a reactionary nostalgia for empire. Or, to put it simply, he longs to Make Russia Great Again.

To safeguard the interests of smaller nations, as well as international peace, Putin ― like other arrogant rulers of powerful countries ― should be encouraged to discard outdated imperial fantasies and accept the necessity of a world governed by international law.

Lawrence Wittner is professor of history emeritus at the State University of New York at Albany and the author of “Confronting the Bomb,” published by Stanford University Press.

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: Putin’s attacks on Ukraine are rooted in the imperialism