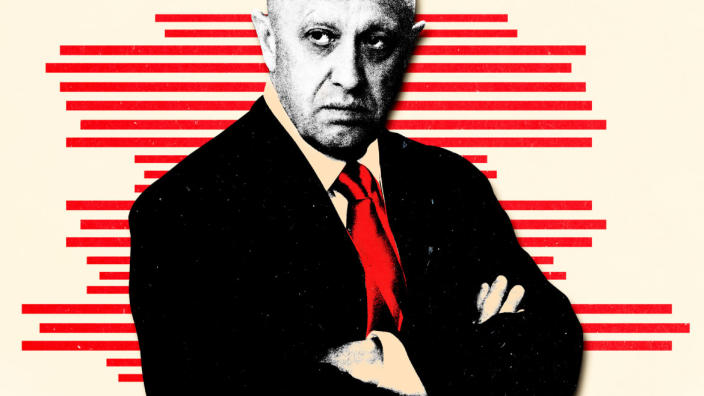

Yevgeniy Prigozhin, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s chef notorious for interfering in U.S. elections, boasted Monday that he has interfered, is currently interfering, and will interfere in U.S. elections. But according to researchers tracking his current meddling operations targeting Americans, Prigozhin’s interference operations might not be as well-resourced or formidable as they once were.

His comment, which came just one day before U.S. midterm elections, is the first time Prigozhin has appeared to fess up to meddling. Prigozhin has been indicted in the United States for interfering in U.S. elections in 2016.

“We interfered, we interfere and we will interfere,” Prigozhin said, according to Vkontakte. “Carefully, precisely, surgically and in our own way, as we know how.”

An element of Russia’s campaigns targeting Americans right now, though, are not going very far.

Suspected Russian actors tied to Prigozhin have been running an influence operation made up of divisive political cartoons aimed at the far-right in the United States in recent weeks, according to researchers tracking interference attempts in U.S. politics at noted research firm Graphika.

After Years of Trump-Russia Denials, Putin’s Enforcer Admits Election Interference

The campaign zeroes in on and disparages Democrats in tight races across the country in Pennsylvania, Georgia, New York, and Ohio. The suspected Russian scheme has gone after the likes of John Fetterman in Pennsylvania, who is up against Republican Dr. Mehmet Oz; Tim Ryan, who is up against Republican J.D. Vance in Ohio, Stacey Abrams in Georgia, and Kathy Hochul in New York. Some of the political cartoons sought to damage President Joe Biden’s reputation as well.

But the overall effect has been minimal, as the network isn’t gaining much traction, Jack Stubbs, Vice President of intelligence at Graphika, told The Daily Beast.

Part of the issue is that the scheme, made up of fake personas online spreading political cartoons, is mostly targeting audiences on alternative social media platforms like Gab, Parler, Gettr and forum patriots.win, which limits its reach. (The small reach could explain some of Prigozhin’s commentary that Russia is now running “surgical” and “precise” influence operations, analysts said.) The other problem is that the Russians’ approach, while it appears clever in some ways, also can come off quite amateurish at times, analysts say.

Compared to 2016, when Kremlin-backed influence operators ran their schemes on the likes of YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook—where Prigozhin’s troll farm, the Internet Research Agency (IRA), spent $100,000 in ad dollars and reached 126 million users—this one appears a little bit scrappier and low-key. In 2020 the IRA went to further efforts to run its operations, outsourcing to teams in Ghana and Nigeria, according to the National Security Agency.

Now, they’re not creating a lot of content, and they’re not creating as many fake personas to try to dupe Americans. Instead, Russian information operations have lately been latching onto pre-existing tensions and posts and amplifying them.

“There’s a broad trend away from creating fake accounts… as opposed to finding people who are already saying the message they want to promote,” Stubbs said.

Some of the Russians’ current approach to interference in U.S. elections online might look somewhat useless at times, Graham Brookie, the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), told The Daily Beast.

“It’s both silly and absurd,” Brookie said. “But it does have some amount of impact. And so we’ve got to monitor and evaluate… to understand whether whether they’re actually causing behavior change.”

Prigozhin’s current operation is unlikely to change anyone’s mind about voting in the United States or in the midterm elections, according to Brian Liston, the lead analyst on Ukraine in the global issues team at security firm Recorded Future.

“This recent network isn’t really something that’s particularly effective,” Liston told The Daily Beast. “These handful of covert accounts aren’t really going to shift the election.”

Part of Russia’s current winnowed down messaging approach focusing on the far right appears to be an effort to further entrench them in their views by validating or confirming existing biases they already have, rather than trying to tip the scales towards one side of the aisle or a particular candidate.

“They’re not looking for their minds to be changed,” Liston said.

At the same time, while the reach may not be far, the Russians may have a trick or two up their sleeves. While they may not be iterating and working up a lot of new content, they are in a way making their lives easier by searching out existing tensions in the United States and working to exacerbate them.

“From time to time it’s sloppy work, it’s not particularly creative,” Liston said.

“But I think also they they can also be resourceful… they understand the U.S. information landscape pretty well, they understand the political and social issues here in the United States that are contentious,” he added. “There’s a little bit of a mix of just being amateur and sloppy, but then also showing a little bit of intuitiveness and creativity.”

But while Prigozhin said he wanted to paint his commentary about Russia’s interference in a “vague” and “subtle” way, he might just be trying to talk up his operations publicly now so that Americans think the Russian operations are bigger and better this year than they actually are, in order to inject doubt into whether Russia is interfering to great effect. Moscow doesn’t even have to interfere to cause chaos in American democracy and leave questions in Americans’ minds about whether a foreign actor has intervened, a move researchers call “perception hacking.”

Russia wants “to just create the specter that they’re doing more than they probably are, or they’re more effective than they are,“ Brookie said. “Saying, yes, we’re doing this, yes, you’ll never know, we’re really big and really bad, that creates a hype cycle that is beneficial to the threat actor in this case.”

“He’s saying these things for attention,” Stubbs added, noting that Prigozhin might be trying to just stir up tense discussions about whether Russia is interfering or not. “One of the most contentious issues in U.S. politics since 2016 has been the threat of foreign interference. No one is better placed to capitalize on that than Yevgeniy Prigozhin himself.”

Russia might have a unique interest in inflating the value of its interference operations right now since the Kremlin appears to not have dedicated a lot of resources to its information operations this year due to the war in Ukraine, which has been a huge pull on resources, Brookie noted.

“They’re probably under resourced from a leadership perspective as opposed to under resourced from a staffing perspective,” Brookie said. “It’s probably harder to set strategic direction at the moment because of so many resource constraints across the board, directly related to the war.”

While the political cartoon campaign from the Prigozhin-linked network is working to push pro-Russia narratives that Ukraine is a Nazi state or that U.S. aid to Ukraine is causing prices to surge in the United States, Prigozhin himself is focused on the battlefield. While he runs political interference operations targeting the United States, he also runs the Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary group that has been fighting in Ukraine.

Putin’s Private Army Accused of Committing Their Most Heinous Massacre Yet

The campaign Stubbs and his team found might confirm that Russia has poor resourcing for its influence operations at the moment. The Russian political influence cartoon network was created in November of 2020 and has been consistently posting since then about American issues. But when January 2022 came around—just as Russia was amassing hundreds of thousands of troops on its borders with Ukraine and gearing up to invade—the network all but ground its operations to a halt.

“We know that these assets were created on November 5, 2020… and they posted every week, every year, until January 2022. And then a large number of the most important assets went dark. For up to nine months,” Stubbs said, noting that this is just correlation, not causation. “The timing of that does align with what we now understand was Russia preparing for Ukraine.”

And while Prigozhin’s work this year on interference hasn’t appeared to have a major impact to date, the Russians or other malicious actors from other countries might be banking on the idea that it could take some time to tabulate votes after midterms and that the dividends from influence operations and amplifying American divisions online might come later.

“Material we’ve seen over the last week or so doesn’t appear to have much online reach,” Stubbs said. “But that doesn’t mean they won’t in the future.”

And while normally Prigozhin-linked operations have been sensitive to being called out, Prigozhin’s network appears determined to stick around, now, which could indicate they have an eye on future operations and influence.

“When you’ve seen IRA operations be publicly exposed and attributed… it does appear to be disrupted thereafter. Their websites typically went dark,” Stubbs said. But this time, even though Stubbs and his team have exposed the network, it’s “still active. It posted six hours ago, as we talk today,” Stubbs said on Monday.

Get the Daily Beast’s biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast’s unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.