For generations, people in South Africa’s Eastern Cape have made their living growing cannabis. You might expect that as the country moves to legalise the crop, they would be first in line to benefit, but that is not necessarily the case.

The drive from Umthatha to the Dikidikini village in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province is a picturesque journey filled with endless vistas, scattered homesteads and winding roads which scythe through undulating green hills that could easily be mistaken for corn fields – yet they are anything but.

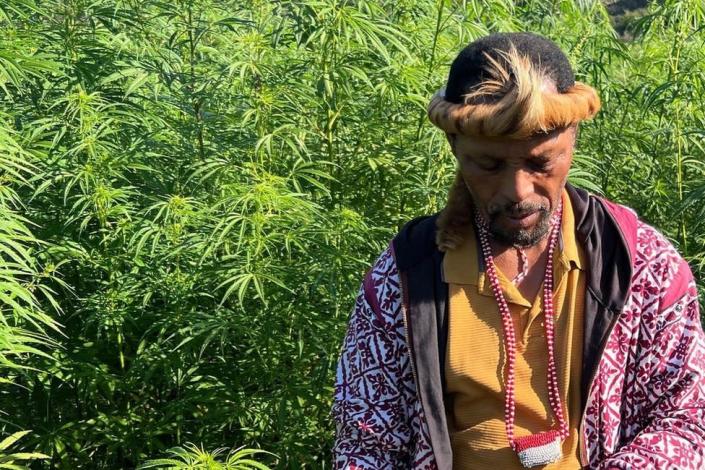

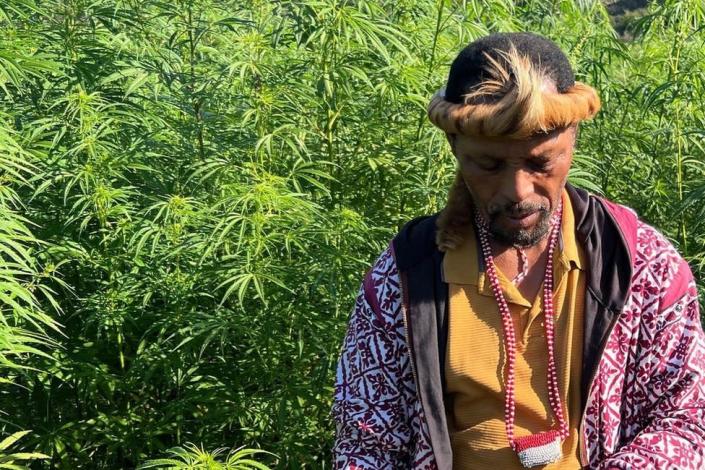

“That’s cannabis,” my local guide and cannabis activist Greek Zueni tells me. “Everyone here grows it, that’s how they make a living.”

Cannabis, colloquially referred to as “umthunzi wez’nkukhu,” or, chicken shade, is an intrinsic part of many rural communities in Eastern Cape’s Pondoland and a vital source of income.

At a homestead near the riverbank, we meet a group of men, women and children tending to a fresh harvest. Their hands are stained green from plucking the cannabis heads all day.

The pungent smell of cannabis hangs heavy in the air. They crack jokes while they work – harvesting is a group effort. A massive heap of green heads lies besides them, drying in the midday sun.

For community member Nontobeko, which is not her real name, farming cannabis is all she has ever known: “I learnt how to grow it as an eight-year-old girl,” she says proudly.

“Cannabis is very important to us because it’s our livelihood and source of income. Everything we get, we get it through selling cannabis. There are no jobs, our children are just sitting here with us.”

While cannabis might be a way of life for this community, growing it at this scale is illegal.

There are more than 900,000 small-scale farmers in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces who have been growing cannabis for years.

These growers have found themselves on the wrong side of the law many times, but the government’s tough stance on cannabis looks set to change.

It started with a landmark court ruling in 2018 which decriminalised the private use, possession and growing of cannabis.

Earlier this year during his State of The Nation Address, President Cyril Ramaphosa said South Africa should tap into the global multi-billion-dollar medical hemp and cannabis industry, which he said had the potential to create 130,000 much-needed jobs.

While this may be good news for commercial companies, traditional growers in the Eastern Cape feel left behind. The cost of getting a licence to grow cannabis is just too expensive for many.

“Government needs to change its approach and come up with laws that are grower-friendly and citizen-friendly. Right now, the people who have licences [to grow cannabis] are rich people,” Mr Zueni says.

“The government should be assisting the communities to grow so that they can compete with the world market. Here is a commodity growing so easily and organically. We are not jealous, the rich should also come in, but please accommodate the poorest of the poor,” Mr Zueni says.

Turning a blind eye

Last year, the government unveiled a master plan for the industrialisation and commercialisation of the cannabis plant. It values the local industry, which has largely been operating in the shadows, at nearly $2bn (£1.6bn).

It is seeking to make South Africa’s cannabis industry globally competitive and to produce cannabis products for the international and domestic market.

Key to the roll-out is the Cannabis for Private Purposes Bill, set to be signed during the 2022-23 financial year, which provides guidelines and rules for consumers and those that want to grow cannabis in their own homes.

It would legalise the cultivation of hemp and cannabis for medicinal purposes, thus opening up the industry for serious investment and growth. It is also expected to clear up legal grey areas and so provide prospective investors with clarity on the future of the South African cannabis market.

Although much still remains unclear, it seems the government is committed to opening up the industry, because the economic opportunities are too enticing to ignore. The plans have broad public support, with few dissenting voices.

While the legal framework is still trying to catch up with a fast-moving market, many companies are forging ahead in anticipation that the law will eventually open up the sector.

As it stands, even though private use has been decriminalised, it is still illegal to buy and sell cannabis and various cannabis products.

However, judging from the proliferation of shops that sell cannabis products around the country, authorities are already turning a blind eye.

Adding to this legal minefield is that it is legal for private companies to grow and export medicinal cannabis to other countries.

‘Opportunities for European distribution are big’

One company that is seeking to capitalise on medicinal cannabis is Labat Africa Group. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange-listed company recently acquired Eastern Cape cannabis grower Sweetwater Aquaponics.

Labat’s director, Herschel Maasdorp, says the company is undergoing significant growth in both Europe and Africa.

It has also listed in Frankfurt, because “Germany is the single largest market in Europe for medicinal cannabis distribution”, he says.

“The opportunities for distribution in Europe are very big. In addition to that, across borders, in Africa alone, there is a proposition that we have consolidated across a number of different countries all the way from Kenya, to Zambia to Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, as well as in Zimbabwe.”

Legal cannabis trade on the continent is set to rise to $7bn as regulation and market conditions improve, says London-based industry analyst Prohibition Partners It says Africa’s top producers by 2023 will be Nigeria with $3.7bn, South Africa $1.7bn, Morocco $900m, Lesotho $90m and Zimbabwe $80m.

In its Global Cannabis Report, Prohibition Partners is forecasting exponential worldwide industry growth: “Combined global sales of CBD, medical and adult-use cannabis topped $37.4bn in 2021 and could rise to $105bn by 2026.”

Considering South Africa’s stagnant economic growth and record unemployment, tapping into the cannabis industry could reap rich rewards.

For Wayne Gallow from Sweetwater Aquaponics, incorporating traditional growers in the industry is crucial for economic development in the Eastern Cape.

“What we wanted to achieve with our licence is not only to grow medicinal cannabis, but to use that licence to benefit everybody in the Eastern Cape,” he told the BBC.

He admits the more traditional growers have been left behind as cannabis legislation progressed.

“The Pondoland area was synonymous with supplying the cannabis throughout South Africa,” he says.

However, changes in the law had a “detrimental” effect on Pondoland farmers, because it meant anyone could now grow and consume their own cannabis, so they no longer had a market for a crop that was previously very lucrative.

Even growing cannabis to export for medicine is not feasible for small-scale farmers, because of the eye-watering costs. It requires a licence from the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) which costs about $1,465.

Besides the licence fee, to set up a medicinal cannabis facility you need about $182,000 to $304 000, which is beyond the reach of many traditional growers.

However, there is some promising news for the Eastern Cape farmers. The Pondoland or Landrace strain of the plant, which grows so abundantly in the area, has shown some encouraging results in treating breast cancer.

Sweetwater Aquaponics and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) are currently running a study, and scientists are optimistic that the strain will yield good results.

It is still early days, but if the Pondoland strain is found to be effective, this could be the game-changer that indigenous growers have been desperately searching for.