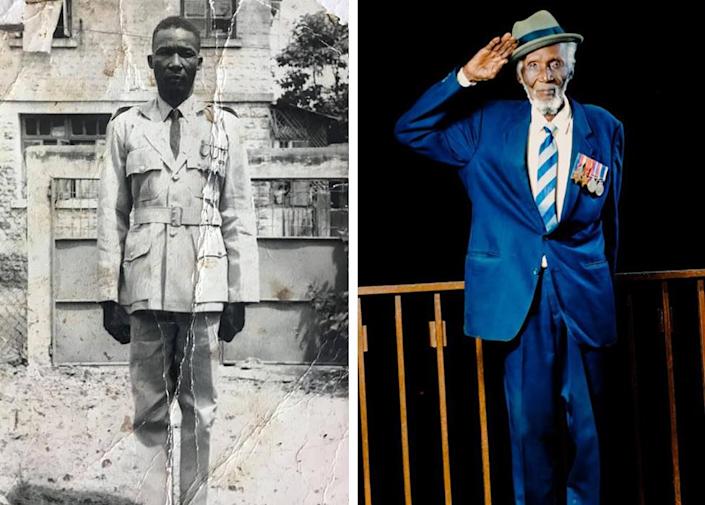

Samuel Sorie Sesay, one of a dwindling group of West Africans who fought in the British army in World War Two, died last month in Sierra Leone at the age of 101. Ahead of his funeral on Friday, Umaru Fofana looks back at his life.

His memories were vivid but he felt forgotten.

Celebrating a century of life in 2020 and surrounded by his large family, Pa Sorie, as he was known, was keen to talk.

Dressed in a neat suit, adorned with his medals, the affable war veteran recounted stories of his time fighting the Japanese in Burma more than 75 years earlier.

He was one of the 90,000 West African troops who were shipped to Asia.

They formed two divisions that are rarely memorialised and fought in a conflict that was overshadowed by events closer to Britain’s shores.

Adding to the feeling of being ignored, Pa Sorie, like many of his comrades, said that he had been promised a lump-sum payment after the war which he never received.

When it came to a pension, the British army did not pay them to World War Two veterans, unless they had been injured in fighting, regardless of where they came from. But a document uncovered in 2019 indicated that African soldiers were paid less than their British counterparts while in service.

Pa Sorie did however get money from a UK-based charity, the Royal Commonwealth Ex-Services League.

Despite lamenting the lack of financial compensation, Pa Sorie maintained that he had no regrets enlisting as a teenager in 1939 and taking part in what he called “the good fight”.

He could still remember the old army songs and clenching his fist he chanted: “Hitler ayy bongolio!”

He said the words were in Hindi but could not remember their meaning. However, the mention of the name of the German dictator gives a hint to what may have persuaded him to sign up.

Pa Sorie talked about facing Hitler’s troops in Burma, despite the enemy there being Japan and not Germany.

Men were recruited into the West African divisions in a variety of ways. Some signed up after they were told they would be fighting Hitler’s racist Nazi ideology, historian Dr Oliver Owen said.

Pa Sorie initially went to Lagos for training – joining Nigerian recruits as well as those from The Gambia and The Gold Coast (now Ghana). They were readied for jungle warfare, which is what they were going to face in Burma.

Hacking and crawling through thick forest in Nigeria, Pa Sorie remembered that they were initially full of fear and uncertainty about what lay ahead but they quickly conquered those feelings, he said.

Once in Asia he took part in what was called the Arakan campaign, aimed at pushing into Burma, which had been conquered by Japan, and preventing its army from invading India.

Pa Sorie recalled a “fight over a very long bridge, which the Japanese wanted to blow up to bar us from crossing. But we overpowered them and went across to set up our camp in the jungle”.

‘Never blinked on duty’

Soldiers experienced harsh conditions, having to make their way through the dense jungle carrying supplies on their heads.

It was a gruelling campaign against an enemy well versed in how to fight in the jungle. As well as that danger, veterans have spoken of some soldiers dying of exhaustion.

Pa Sorie remembered how he once fell asleep on duty. When he woke up a British soldier was holding a machete over his head and, in what Pa Sorie took as a joke, threatened to kill him.

That changed his military awareness for ever.

“Once I survived that I never even blinked again on duty,” he said with a broad smile.

Following the end of the war he went into the civil service in Sierra Leone and ended up working in the country’s mission in what was the USSR.

But his war efforts were not celebrated either before or after independence in 1961.

He was not feted by the government and despite being one of the last World War Two veterans in Sierra Leone was not well-known in the country.

But still able to walk without a stick well into his nineties, Pa Sorie was a familiar figure near his home, determinedly climbing the hills of the Tengbeh Town area in the west of the capital, Freetown, according to his grandson John Konteh.

“He was a very resilient human being, and represented and embodied our character as a nation as a resilient people,” Mr Konteh said.

At his funeral on Friday, Pa Sorie’s family will remember his war effort and hope that others will begin to recognise his contribution and those of his comrades.