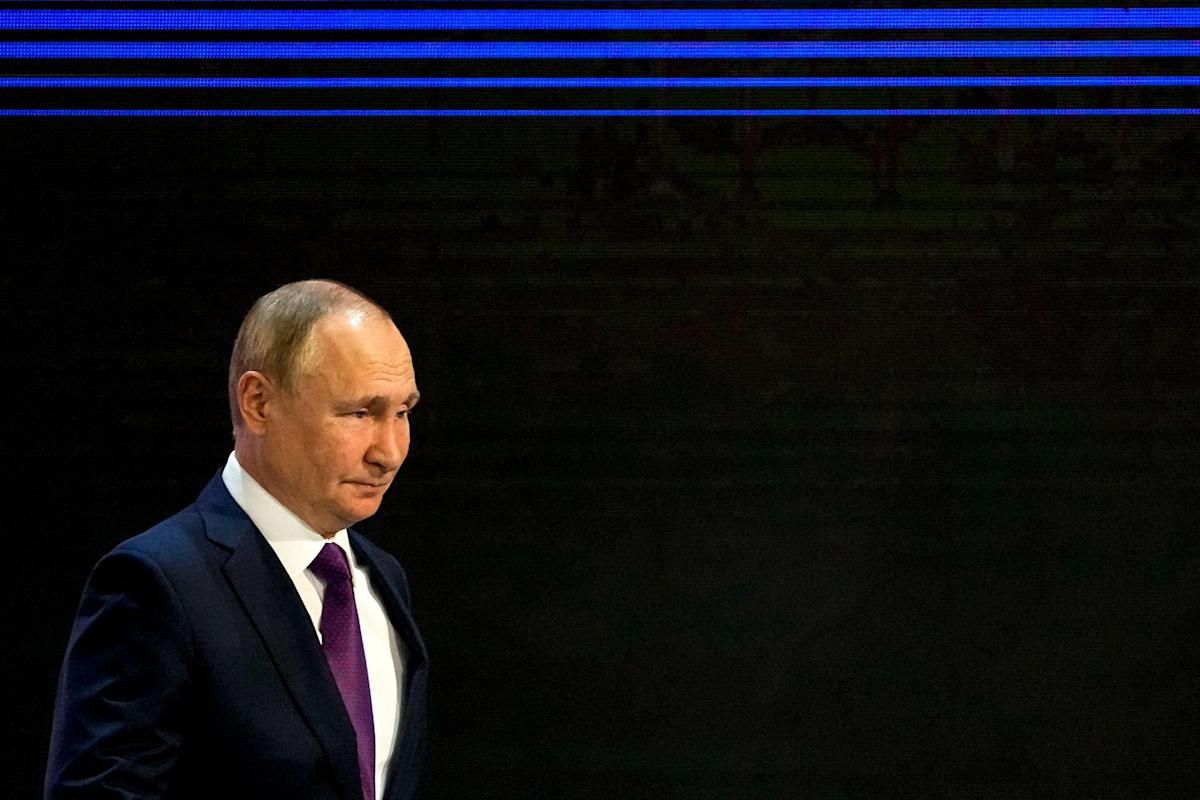

President Vladimir Putin’s recognition of the separatist republics of Luhansk and Donetsk, which opened the door to the wider assault on Ukraine that is now underway, is a game-changer on a historic scale. It underscores, like nothing else, that the drift away from Europe by the United States over the past 20 years in pursuit of wars and priorities elsewhere has been short-sighted. Like 1949, the year in which the North Atlantic Treaty Organization came into being, America and its European allies are facing a moment requiring a profound redefinition of their security, political and economic ties.

Going forward, a strategic, not tactical, pivot back to Europe should be the driving imperative of American foreign policy. In doing so, it is important to accept reality: Putin called the bluff of the not-very-collected West, which was equivocating by placing only selective sanctions on Russia for its virtual annexation of part of Ukraine. Putin is unlikely to be deterred by a staggered escalation of these measures meant to allow room for him to change course: He is dead set on achieving at least a partial reconstitution of the Russian empire as he sees it and forcing the creation of a new security architecture for Europe. Putin’s words need to be taken seriously instead of being dismissed as ramblings or misleading. For all the lingering suggestions that there is still time for diplomacy, Putin could not have been clearer this week that he was also setting the stage for more aggressive steps in the very near future. He even raised a non-existent nuclear threat to Russia from a NATO-dominated Ukraine and again dismissed Ukrainian national identity as a fiction.

Arriving at this point, too many commentators and politicians spent months resorting to dismissive rhetoric about Putin even as he outmaneuvered Western leaders. They belittled Russia — as a declining power, a declining economy and as a nation fearful of democratization on its borders. They argued that the United States and NATO allies could force Putin to rethink his actions — even though there has been no sign of him reconsidering course. Some argued that Putin would not risk war given the likely costs. It is now possible to see the limits of their world view.

The inviolability of a nation’s sovereignty and its right to decide its own security alliances have also been presented as self-evident truths. In the case of Ukraine, however, many of us side-stepped uncomfortable questions about why NATO did not invite the country to join, and about the precedents set for Finland and Austria after World War II to ensure their neutrality. A now prophetic article by Henry Kissinger in 2014 makes it clear that something like the neutrality option would have been a more desirable outcome for Ukraine and reflected the reality of Ukraine’s situation.

The West will find it difficult to break the momentum that Russia is building, or to reverse the new realities Putin is creating. Russia may not be a colossus, but it remains one of the most powerful countries in the world, with a nuclear arsenal, a modernized military and a serious player in international oil and gas markets. It cannot, in other words, be dismissed only as a “regional power threatening its neighbors out of weakness,” and while it is becoming an outright dictatorship by smothering democracy at home, that is not a central concern in the current crisis. Russia can project its military globally — as its interventions in Syria and elsewhere have shown. It can wage cyberattacks on Europe and the United States with relative impunity. Putin has triumphed in political showdowns with leaders like Turkey’s President Erdogan and, even as Russia’s relationship with Europe in general turns adversarial, the likes of Serbia and NATO member Hungary appear more sympathetic to Putin. World leaders until last week came to Putin as he limited his own international travel — and gave little away. Russia’s diplomatic fortunes are hardly crumbling elsewhere, as evidenced by a rising entente between China and Russia — aligned in their security interests against perceived Western encroachment.

There is another factor at work, and that is that Putin’s view of history, often seen as opportunistic, does appear to be a primary driver of his actions. And it is not his worldview alone. The incorporation of Russian-speaking populations inside neighboring borders after 1991 remains an issue for nationalists in Moscow; and the West has systematically downplayed how NATO expansion since 1997 has looked to a generation of Russian leaders, and not just President Putin. It is not dovish, as a recent New Yorker article suggested, or appeasement as a British defense minister stated, to take these perceptions into account in the current crisis. The deep undercurrents of historical myth drive almost every nation into destructive paths.

It is in this context that the United States and its allies have chosen to draw a line in the sand over a further Russian military intervention in Ukraine which has now materialized on a major scale. The relative success of President Joe Biden in preserving a united front with European allies on a gradual escalation of sanctions masks the lingering challenges of fully cohering on strategy. There have been differences between the responses by the United States and Britain on the one hand; the French and the Germans on another; and disparate governments like Italy (opposed to energy sanctions as late as this past weekend) and Hungary (offering veiled sympathy to Russia’s demands). French President Emmanuel Macron until recently was openly discussing the need for a new security architecture for Europe. Chancellor Olaf Scholz of Germany told national reporters on his return from Moscow that “we just can’t have a possible military conflict over a question that is not on the agenda” regarding Ukraine’s future membership in NATO. As EU foreign ministers met in Brussels this week, there were continued differences between those arguing for “incrementalism” on sanctions like Germany and Italy, and those wanting a more forceful response. There may be greater unity now as the scale of the Russian invasion becomes clear, but the proof will only be evident in the coming days.

The allies’ caution in recent days contrasted with President Zelensky’s increasing concern as options close around him. The gathering of senior NATO and EU ministers at the Munich Security Conference on Feb. 18-20, as well as the presence of a U.S. delegation led by Vice President Kamala Harris, did not convey the strongest confidence on an agreed approach to Russian aggression. President Zelensky’s speech at the gathering was a searing indictment of the lack of decisiveness of Western nations over the last many years, and Ukrainian ministers were publicly critical of the slow pace of the imposition of sanctions since the recognition of the separatist republics by Russia.

Western governments are now at a real, not hypothetical crossroads. The invasion is underway, and Putin would appear to be achieving his long-stated objectives, some of which he began to make clear 15 years ago in a speech to the 2007 Munich Security Conference. He has torn up the 2015 Minsk agreement which was meant to be the foundation for talks between Ukraine and Russia regarding the future of the Donbas. Putin is calculating he can survive sanctions for an indefinite period as he builds a significant war chest of foreign reserves. He is also betting on a swifter and easier military victory in Ukraine than Western analysts are predicting. If either of these scenarios were to hold, NATO, EU and American threats or actions would end up ringing hollow to most of the rest of the world.

Putin, in short, means to complete what he has started, and more. As Lithuanian Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis suggested, Ukraine may not be the end of the story, and Belarus’ renewed and total subservience to Moscow can, in retrospect, be seen as prelude to Putin’s attempt to do the same to Ukraine.

In responding to Russia’s expanding aggression in Ukraine, Western nations will build towards ever more severe sanctions. There will be United Nations resolutions and condemnations. Russian oligarchs may lose their right to residence and investment in London and Paris. Nord Stream 2 is being suspended and may be canceled. NATO may be strengthened; European members may finally spend 2 percent of their GDP on defense. NATO may accelerate military assistance to Ukraine or arm an insurgency in Ukraine in the future. The broader international community may be galvanized into supporting harsher measures to punish Russia depending on the scale of the conflict.

Longer-term, however, the latest developments suggest it is time to rethink the West’s approach to the next phase of dealing with Putin. That will entail recognizing that the security landscape of Europe is being changed as we watch, in real time, and is unlikely to be turned back to what it was any time soon.

The response must stop Russia from destroying the post-World War II architecture that has largely preserved peace for 70 years. Doing so will require another historic decision and response. We need to revitalize NATO and the transatlantic economic and political relations which have been weakened for two decades as the United States prioritized Asia, abandoned trade agreements, diverted NATO to fight wars farther afield and allowed allies to take for granted the alliance’s centrality to their own collective defense. In the process, we may rediscover that the future of the United States is still most fundamentally impacted by what happens in Europe.