Last weekend, the Vienna Philharmonic returned to New York for three performances, its first appearances in the United States since 2019. On the day before the opening concert, Carnegie Hall announced that the man slated to lead the programs, Valery Gergiev, the esteemed Russian conductor and Vladimir Putin’s friend and supporter, would not appear. The reason, according to a spokesperson, was “recent world events.”

With the invasion of Ukraine, people in both the U.S. and in Europe have demanded to hear from Gergiev. To this point, he has remained silent. As a result, he has been dismissed from several positions in Europe, raising crucial and even painful questions for American concertgoers, orchestra administrators and the public.

Is it reasonable to ban an artist if he or she consorts with a toxic regime or embraces policies we find repugnant? Does music transcend politics?

In considering the decision to keep Gergiev off the stage — a justifiable one given his silence in the face of Putin’s invasion — we ought to recall that Americans have long grappled with such questions.

During World War I, anti-German hatred washed over the American landscape. German-language books were burned. German music was banned, German musicians lost their jobs, and two celebrated symphony conductors, Ernst Kunwald (an Austrian) and Karl Muck (a German), were stripped of their positions in Cincinnati and Boston. Both were sent to an internment camp in Georgia, where they languished, along with thousands of “enemy aliens” of German heritage, until the war’s end. Neither had broken any law, but they were deported in 1919, illustrating the odious intolerance of the era.

A more complicated case concerns another celebrated German maestro, Wilhelm Furtwängler. Furtwängler became the target of anti-German hostility in the United States, when he accepted invitations to take the reins of the New York Philharmonic in 1936 and the Chicago Symphony in 1948. In neither case did he come to America. The intense public opposition kept him away.

Furtwängler spent the 1930s and the war years living and working in Hitler’s Germany. Many Americans were outraged that an artist so closely linked to the Nazi regime was invited to take up a position in the U.S. As head of the Berlin Philharmonic, they saw him as a tool of the Hitler government.

In both 1936 and 1948, heartfelt letters opposing his American presence flooded the newspapers. In 1948, a Chicago reader rebuked Furtwängler’s supporters for speaking about the “sanctity of art.” He declared that “a knife wielded by an artist will cut as surely as that wielded by a butcher.”

But Furtwängler had supporters. He was not a member of the Nazi Party, nor was he seen as backing the regime. He had refused to dismiss Jews from the Berlin Philharmonic (early on, at least).

Throughout those years, Furtwängler claimed that music and politics were separate realms. When he decided not to come to New York in 1936 because of the intense local opposition, he cabled the orchestra: “Am not politician but exponent of German music, which belongs to all humanity regardless of politics.” He would come to America, he said, when “the public realizes that politics and music are apart.”

A Time magazine headline was more succinct: “Nazi Stays Home.”

After the war, Furtwängler claimed he had continued working under the Nazis because he thought it would allow him to help preserve for future generations the cultural achievements of an older, nobler Germany. For many, that argument rang hollow.

Should we imagine Gergiev as a latter-day Furtwängler? Whatever one makes of Furtwängler’s explanation for his wartime actions, Gergiev has chosen a different path.

He certainly hasn’t kept music and politics separate. Gergiev and Putin have had a close relationship for three decades. In 2012, Gergiev appeared in a campaign video supporting Putin’s presidential candidacy. In 2013, the conductor was one of five recipients of the Hero of Labor of the Russian Federation Prize, an award from the Stalin era, which Putin revived.

That same year, Gergiev’s performances at the Metropolitan Opera and Carnegie Hall were interrupted by gay rights activists who demanded to no avail that he explicitly repudiate the Russian president’s repressive anti-gay legislation. And the following year, Gergiev supported Putin’s annexation of Crimea, a portent of things to come.

While it may be possible to make the case that music and politics occupy separate spheres, Gergiev cannot credibly do so. Over several decades, he has hitched himself to the Russian leader, which has necessarily politicized his every move.

Should Gergiev decide to stop hiding behind the notion that art and politics are apart, he might be able to resume his career as an artist with integrity.

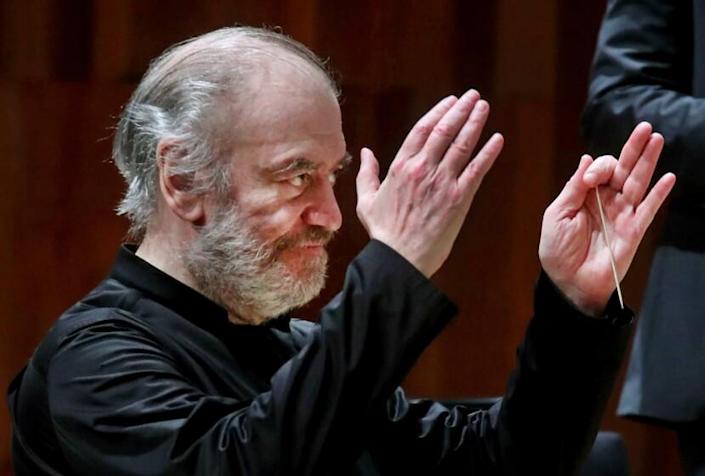

The other night, in Chicago, the revered Italian conductor Riccardo Muti, who leads the Chicago Symphony, spoke to the audience just before a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Reflecting on the suffering of the people in Ukraine, Muti said he hoped his musicians would send a message to all people, not just in Ukraine, but around the world, who “are creating violence, hate and a strange need for war. We are against all that.”

Now that Gergiev has some extra time on his hands, I hope he has the chance to watch the video of what Maestro Muti had to say.

Jonathan Rosenberg is a professor of history at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. He is the author, most recently, of “Dangerous Melodies: Classical Music in America from the Great War through the Cold War.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.