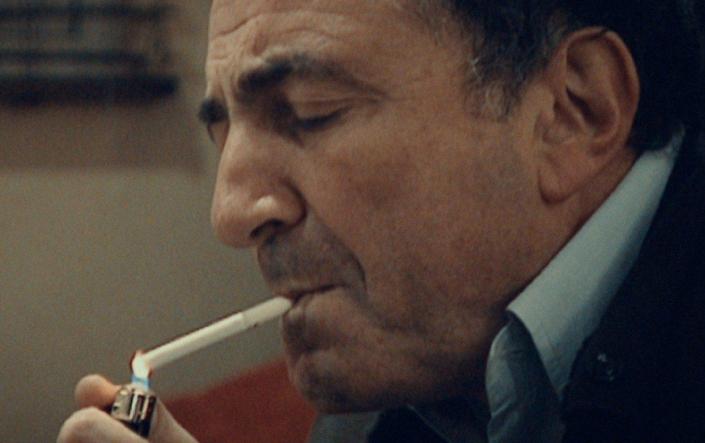

Once Upon a Time in Londongrad (Sky Documentaries) arrives at a timely moment, with the invasion of Ukraine fixing a spotlight on the murky world of super-wealthy Russians in the UK. This is a meaty – if sometimes disorientingly dense –film about the suspicious death of Scot Young, a flash, Ferrari-driving wheeler dealer with links to the community of Moscow high-rollers who fled Vladimir Putin’s regime to pursue a blinged-up life in London.

The series occasionally bites off more than it can chew. The story begins with Young, who plunged to his death from his girlfriend’s fourth-floor flat in Marylebone in December 2014. The police discounted suggestions he had been murdered, while the coroner refused to confirm he had died by suicide. His ex-wife, Michelle, was convinced there was more to the story, refusing to believe Young would have jumped out a window (for one thing, he was afraid of heights).

Her theory is taken up by BuzzFeed, which the film acknowledges is best known for its articles about cats. But this is where an already tangled thread becomes frustratingly knotty. Young was a fixer for Boris Yeltsin associate Boris Berezovsky, whose fortune of £10 billion had shrunk by £9 billion after a falling out with Putin and who is described by one colleague as a sort of Schrödinger’s Oligarch, simultaneously “kind and evil”.

Berezovsky was found hanging in the bathroom of his house near Ascot in 2013 in what was initially believed to be suicide. However, conflicting evidence meant the coroner could not rule definitely as to how he had died. Question marks also dangled over the fatal heart attack 12 months previously of whistleblower Alexander Perepilichnyy, who collapsed while jogging near his home in Surrey.

Once Upon a Time in Londongrad gets into the granular detail of these and other suspicious deaths that BuzzFeed identified as potentially linked to Russia – 14 in total – across its six half-hour episodes. And if the tale is told briskly, it never quite connects the dots or establishes beyond doubt that Young, Berezovsky and Perepilichnyy were victims of targeted Kremlin assassination.

Yet the questions posed are nonetheless worth asking. Why were police and politicians so quick to write off the deaths as suicide or, in the case of Perepilichnyy, the result of an iffy serving of sushi? And how was it that these opinions were not revised after the 2018 Salisbury poisoning case confirmed beyond all doubt that Moscow was prepared to target dissidents considered a threat to Putin?

“He needs to keep everyone absolutely terrified,” says Bill Browder, the financier who fled Russia after clashing with Russia’s vengeful president. “To make it absolutely clear terrible things will happen if you cross Putin.”

Once Upon a Time in Londongrad doesn’t always come across as confident in its arguments. In the final episode, a rotating cast of former Russian intelligence figures and British police line up to pooh-pooh the idea that Young was the target of a Russian hit.

But the film has already made its point, which is that London is awash with dirty Russian money – and that dirty money often leads to dirty deeds. We may never know how or why Young ended up tumbling from that window in Marylebone. Once Upon a Time in Londongrad’s unsettling message is that the corrosive influence of oligarchs and their wealth goes far beyond one suspicious death.