In our series of letters from African writers, Nigerian novelist Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani writes about a new initiative to reclaim artwork looted from Africa by colonial powers.

What if Africans somehow managed to access museums across the Western world, gather all the artwork looted from their territories during the colonial era, and take them back home?

A young Nigerian man is attempting to do just that. But rather than physically breaking into museums and carting away the works of art, he wants to repatriate them digitally.

“This is the first digital repatriation of stolen artwork,” said 34-year-old Chidi, a Nigerian creative designer and founder of Looty, who declined to give his surname because, he said, he wants people to focus on his project and not his person.

“I had this idea that: Why don’t we take back the physical works of art into the digital world?”

The idea of Looty first came to him following the growing conversations around non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which claim to provide public proof of the ownership of digital files.

While the legal rights conveyed by NFTs can be uncertain, they are becoming increasingly popular.

The NFT of the first tweet by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey sold for $3m (£2.4m), and another of the arrest warrant for South Africa’s late anti-apartheid icon Nelson Mandela raised $130,000 at an auction.

The NFT conversations are happening at the same time that there is increased agitation for the return of artwork stolen from Africa by European colonisers.

“We were talking about provenance and ownership of the pieces. What if I was able to take them back and turn them into NFTs?” Chidi said.

The process of repatriating the artwork starts with researching potential pieces for Looty, then going to museums to scan them using special apps on mobile phones.

Afterwards, the images are downloaded on to laptops and the complicated process of converting them to 3D begins, using special apps and technology.

“To be honest, it is almost like we are re-sculpting the artwork again,” Chidi said. “One piece can take like a whole week to finish, maybe more.”

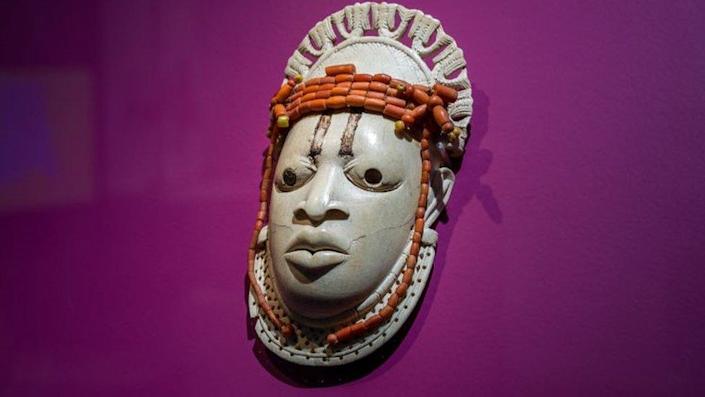

Benin Bronzes digitally created

The Looty website will be formally launched on 13 May, but the work began in November 2021.

While Chidi is the founder, he works with two other Nigerians and a Somali.

Each member of the team specialises in 3D design, NFT technology or editing, but they have all visited museums in the UK and France to capture images of the artwork with their mobile phones.

So far, they have managed to create about 25 different pieces, including some of the famous Benin Bronzes that once decorated the royal palace of the kingdom of Benin in what is today Nigeria, and have their sights set on many more.

More about Africa’s looted artwork:

Chidi says he is aware that the word “Looty” is linked to “looting”, which is an act of violence, but points out that there is a deeper meaning to his choice of name for the project.

In 1860, a British serviceman, Captain John Hart Dunne, returned to England from Peking (now Beijing) with an unusual dog which he presented to Queen Victoria as a gift for her “royal collection of dogs”.

Named Looty in reference to its origins, the famous dog that sometimes sat for paintings and sketches by acclaimed artists, was reportedly taken after the British sacked a royal palace in Peking.

Looty was one of the first in the UK of what became known as Pekinese dogs, and lived in Windsor Castle until its death in 1872.

In 2018, rumours were rife in the media of the Chinese government’s involvement in a wave of art heists that targeted Chinese art and antiquities in the West.

The Chinese government denied these claims, even after one of the stolen artwork re-appeared on display at an airport in Shanghai.

“Before the British were looting artefacts in Africa, they had already made a fortune from the things they stole from China. In choosing the name ‘Looty’, I am referencing that, but also referencing the dog that was given to Queen Victoria,” Chidi said.

“Even though we are called Looty, we are doing it in a non-violent way and also a legal way.”

Chidi’s vision for Looty is two-fold. First is repatriation, which reclaims the stolen artwork and links them with local museums in Africa, arts organisations, and Africans in general whom he describes as “the original owners of these pieces”.

Second is reparation, aimed at helping artists across Africa, whom he believes also had opportunities for inspiration stolen from them by the British looters.

“If you live in maybe Benin and you want to be inspired by the artwork that comes from your ethnic group, first you need to apply for a visa, then buy the ticket for a plane, get to England and book hotels. You then go and view the artwork. There are not many people who are going to be able to do that,” Chidi said.

‘Building a metaverse’

Chidi hopes that viewing the artwork on Looty will not only inspire African artists at home, but also that the sale of the artwork will make funds available for local artists to advance their craft.

NFTs of artwork on the website can be purchased only with cryptocurrency.

“The token is basically a digital contract. On purchase of any pieces of artwork on Looty, 20% of that will go to the Looty Fund. From that fund, we are going to start giving grants to artists from the continent. We will donate money and equipment for artists to use,” he said.

While Chidi hopes that all the activism will eventually lead to the return of every single piece of artwork looted from Africa by the colonialists, he continues to dream of an alternative.

“I want to build our own metaverse where these pieces will live and can live,” he said.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica