British police are keeping a stolen statue worth millions of dollars in their custody as a dispute rages between a Belgian antique dealer and a Nigerian museum over its ownership, writes Barnaby Phillips.

The 24th of January 2017 was a cold, foggy day in London.

At midday John Axford, of the auctioneers Woolley and Wallis, was in his office in upmarket Mayfair, waiting to meet a visitor from Belgium who wanted to show him a sculpture.

“He produced this particularly beautiful piece,” said Mr Axford.

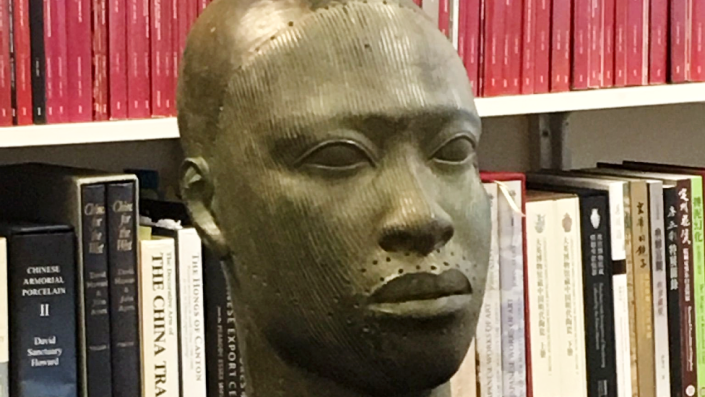

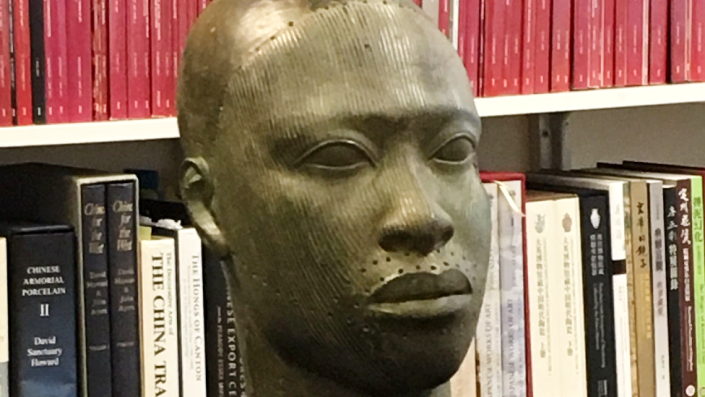

It was a bronze cast head, which Mr Axford recognised as coming from Ife, a Yoruba kingdom in what is today south-western Nigeria. Original Ife bronze heads, of which only some 20 survive, are thought to be about 700 years old.

They are cast in thin metal with great skill and are strikingly lifelike, amongst the most magnificent sculptures ever made in sub-Saharan Africa.

“This kind just does not turn up commercially,” said Mr Axford.

But the sculpture had a hole by the left eye, which matched the description of a head reported stolen by the UN’s cultural organisation, Unesco.

“I realised we had a problem,” said Mr Axford. “If it was legal, it would have been worth £20m ($17m). I told the man it was a wonderful piece, but we can’t sell it. We had to give it to the police.”

The man left. Mr Axford, afraid to let the sculpture out of his sight, slept with it at his bedside. The next morning he gave it to the British police, who’ve had it ever since.

To follow this story to Mayfair, we must first go back almost exactly 30 years, to the city of Jos in central Nigeria. On the night of 14 January 1987, thieves broke into the Jos Museum. A guard was severely beaten. The thieves knew what they wanted – they made off with nine of the museum’s most precious treasures.

In the 1980s and ’90s Nigeria’s museums suffered many damaging robberies. Staff from within Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) collaborated in some of the thefts. A former employee at Jos Museum told me she was in no doubt that this robbery was also an inside job.

The NCMM instantly alerted Unesco, providing photographs of everything stolen from Jos.

In 1990 collectors in Switzerland were approached by a man trying to sell a beautiful Benin Bronze head for a half a million Swiss francs. The collectors were suspicious, and with the help of American, Swiss and Nigerian diplomat,s it was identified as having come from Jos and was returned to Nigeria.

Meanwhile the other eight pieces had, apparently, vanished. Most of them, including the Ife head, are listed in a 1994 publication by the International Council of Museums (ICOM), entitled One Hundred Missing Objects; Looting in Africa.

It wasn’t until many years later, in bizarre circumstances, that the Ife head would reappear, in Belgium.

On 14 November 2007, the Belgian authorities held an auction of confiscated art items. Among the lots was the Ife head. It was bought by a local antique dealer, for the princely sum of €200 ($210; £170), plus 20% tax. He bought an acoustic guitar at the same auction.

This extraordinary sale raises three obvious questions: how did this stolen treasure come into the hands of the Belgian authorities; why did they let it go; and did the dealer know he was buying one of Africa’s greatest masterpieces?

Unfortunately, the Belgian government cannot throw any light on the matter, but says the public prosecutor’s office in Ghent has launched a judicial enquiry.

The Nigerian authorities are incandescent, not least because Belgium’s failure to answer these questions may make it impossible to ever discover what happened to the other pieces stolen from Jos. Babatunde Adebiyi of the NCMM said Belgium’s inability to explain what happened is “ridiculous”.

As for the antique dealer, I managed to track him down. We had a short, terse telephone conversation.

“Did you know you were buying stolen property?” I asked the man, who we have decided not to name.

“Of course I didn’t, I bought it from the Belgian state,” he replied, and put the phone down.

The story then leaps forward 10 years, to London and 2017, when the dealer tried to sell the head through Woolley and Wallis, who passed it on to the British police. In 2019 the police took the head to the British Museum, where curators confirmed its authenticity by comparing it with a cast that was made in the late 1940s.

“I feel confident it’s genuine,” said an expert who saw it.

Otherwise, the head has been sitting in a secure police facility for the past five years. So why won’t the British give it back to Nigeria?

This is where the story becomes mired in legal complications. The Nigerian government has asserted its ownership claim to the British police, and raised the matter with the British government. It complains it has been dealt with “brusquely”. But the dealer refuses to relinquish his claim.

“Everyone agrees this piece was stolen,” said a British official, “but has the Belgian dealer, in legal terms, done anything wrong? He bought it in a government sale.”

!["I told him [the antique dealer] he could be an international hero. He said he wanted money, not people saying nice things about him"", Source: Babatunde Adebiyi , Source description: Nigerian museum official, Image:](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/STg8qRg7LdkJ9vkTH.6HAA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTcwNQ--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/tDieC7VZFVaglUrUIESymw--~B/aD0wO3c9MDthcHBpZD15dGFjaHlvbg--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/bbc_us_articles_995/393659a02ee73250714041a302111057)

!["I told him [the antique dealer] he could be an international hero. He said he wanted money, not people saying nice things about him"", Source: Babatunde Adebiyi , Source description: Nigerian museum official, Image:](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/STg8qRg7LdkJ9vkTH.6HAA--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTcwNQ--/https://s.yimg.com/uu/api/res/1.2/tDieC7VZFVaglUrUIESymw--~B/aD0wO3c9MDthcHBpZD15dGFjaHlvbg--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/bbc_us_articles_995/393659a02ee73250714041a302111057)

The British police insist they are neutral.

“Whatever our private preference, we can’t take property from an individual,” said an official. “This has to be resolved between the Nigerian government and the dealer.”

In 2019 a Nigerian delegation met the dealer. The atmosphere, according to Mr Adebiyi, was “cordial”. Mr Adebiyi pleaded with him. “I told him he could be an international hero. He said he wanted money, not people saying nice things about him.”

The Nigerians say that at times the dealer has asked for €5m, but has brought his price down. British officials tell me he is now asking for €39,000 (£33,500).

In our brief phone conversation, the dealer told me he’s been talking to the Nigerians for three years, and a resolution of this matter depends on them.

But why should Nigeria pay to retrieve its own stolen property?

“We reported its loss in 1987. We will not pay compensation,” insisted Mr Adebiyi.

One possible solution, suggested by the British, is that the Belgian government, having made the disastrous error of selling the head in 2007, now pay off the dealer. The Belgian government would not comment on this, but told me that as Nigeria had taken Britain before a Unesco advisory body to try to resolve the case, it “continues to encourage dialogue” between them.

The current debate in Europe over colonial legacies, and specifically over African cultural heritage in European museums and collections, ought to strengthen Nigeria’s position in this dispute.

I asked Mr Adebiyi, given this piece’s value, whether we should be concerned about its security should it return to a Nigerian government museum.

“1987 is different to 2022. Such a robbery could not occur today. Our officials are much better trained,” he insisted.

In the meantime, a British official assured me, the Ife head is being well looked after.

“This is a fabulous piece,” the official said, “but it’s a travesty that it is not in a museum, and preferably the one it was taken from.”

Barnaby Phillips is a former BBC Nigeria correspondent, and the author of Loot; Britain and the Benin Bronzes.