BALTIMORE — Jonathan Martin believes he’s doing most things right.

A former offensive tackle with the Miami Dolphins and San Francisco 49ers, he retired at 26 before the sub-concussive head hits that are the hallmark of his position could do more damage. He shed 50 pounds, took up yoga and meditation and, after bouncing from job to job, enrolled in an M.B.A. program at the University of Pennsylvania.

But Martin, now 32, figures he had potentially dozens of concussions playing football and has had bouts of anxiety and depression, all symptoms associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative brain disease that has plagued football players.

Martin’s concerns led him, in 2019, to join a study at Johns Hopkins University that could help scientists develop treatments for the symptoms and illnesses linked to brain trauma and C.T.E.

“I wanted to be at the forefront of a solution,” said Martin, who was the target of a teammate’s bullying that made headlines in 2013. “There should be more awareness around head injuries. I want to know how I can keep my mind lubricated.”

The study, now finishing its second phase, looks at why the brains of former football players continue to work overtime to repair themselves years after the athletes stopped playing. Using PET scans, researchers track the brain cells known as microglia, which remove and repair damaged neurons. Those cells are typically active after trauma, including concussions, and become less so as the brain heals.

“The microglia and the molecule they’re working with are basically the sanitation workers of the brain,” said Jonathan Lifshitz, the director of the Translational Neurotrauma Research Program at the Phoenix Children’s Hospital who is not involved in the study at Johns Hopkins. “They’re like FEMA: They’re on high alert, and when they’re needed, they’ll come in and act.”

Head Injuries and C.T.E. in Sports

The permanent damage caused by brain injuries to athletes can have devastating effects.

Active microglia are normally welcomed as they help the brain repair itself, but their remaining active so long after trauma has ended may mean that other problems are emerging.

While the activity of those microglia has been found in others who have suffered brain trauma — people in car crashes, for instance — those groups can be hard to find and track through the duration of a time-consuming study. N.F.L. players, though, are a discrete group who can be easy to identify and, like Martin, can be eager to take part.

Dr. Jennifer Coughlin, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the study’s lead researcher, first observed the overtime work of the reparative brain cells in a pilot of the study that began in 2015. Testing four active N.F.L. players and 10 former pros whose careers ended within 12 years, Coughlin’s team found higher levels of a biomarker that increases as microglia activity does.

That chronic activity, she said, might be a sign that players are at risk of developing other problems linked to brain trauma, such as deteriorating memory, mood disorders or Alzheimer’s disease.

“We want to know whose brain is healing and why,” Coughlin said. “That could inform new treatments.”

To get more clarity, Coughlin and the researchers focused the study’s second phase on younger former players, who were less likely to have vascular disease or other indications that might independently muddy the interpretation.

Martin, who since the bullying scandal had battled depression that deepened after he left the N.F.L., wondered if football played a part. He reached out to the Concussion Legacy Foundation to learn more about any potential links, and the group pointed him to the Johns Hopkins study.

“Based on some of my behavior, the question came to mind: Is there something wrong with me beyond just normal depression?” Martin said. “Anyone who plays football knows that smashing your head isn’t good for you.”

He was first examined in late 2019 and, after a delay to the study because of the coronavirus pandemic, returned to Baltimore in March for two days of follow-up tests.

On the first day, Martin answered questions about changes in his cognitive abilities and mental health since his first visit. The next morning, he returned for a PET scan, an imaging test that would monitor his brain activity by tracking a chemical injected into his arm.

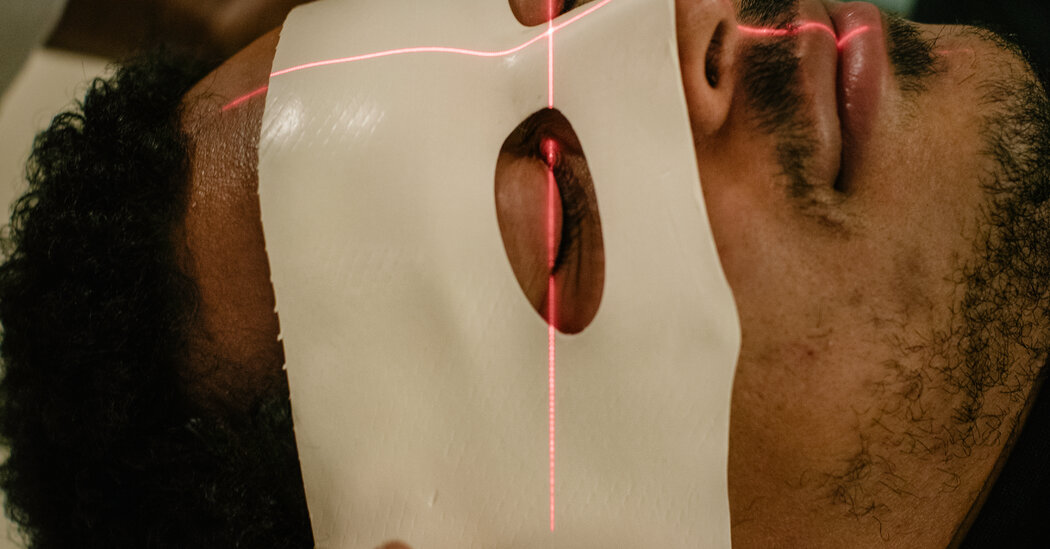

During the 90-minute scan, Martin meditated to get over the claustrophobia of having his head inside a tightfitting metal cylinder for so long. Karen Edmonds, a nuclear medicine technician, fitted him with a wet mold that, once hardened, would keep Martin’s head still.

“Once it’s molded, it fits like a glove,” she said.

An anesthesiologist then put a catheter in Martin’s left arm for the 35 or so blood samples that would be collected during the scan.

Once in the PET-scan room, Martin lay on his back on a table with a blanket draped over him and was slid backward until his head was inside the scanning tube. Then the tracing agent was injected into his right arm, and Edmonds watched its progress on a monitor.

“The goal is to see how much of the radio tracer lights up in the brain,” Edmonds said. “There’s just one dose at the beginning, and then we monitor to see how fast it deteriorates.”

After the test ended, Edmonds pulled the table with Martin out of the tube. “I have claustrophobia, but I just breathed through it,” Martin said. “You’re definitely bored, but it’s finite.”

Coughlin arrived to remove the arterial catheter, which took about 15 minutes.

She has so far tested 22 former N.F.L. players and 25 other athletes, and she hopes to test 70 participants in all, better to isolate potential factors that cause the brain activity. Genetics, other medical conditions, the player’s position on the field and when he started playing football could all be contributors, Coughlin said.

“This will allow us to parse through to determine what factors there are for people with persistent brain injury,” she said.

Even with Martin and other players’ participation, the Johns Hopkins study is still a relatively small one and just beginning to understand how traumatized brains behave. But it has the potential to help identify the early onset of illnesses and symptoms linked to head trauma, not just in football players but in people previously involved in bicycle accidents, car crashes and other collisions.

“Right now, there’s no real good way to diagnose Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease early,” said Jay Alberts, a neuroscientist at the Center for Neurological Restoration at the Cleveland Clinic. “It’s so important to be able to raise a yellow flag or red flag.”

The study is blind, which means Martin and the other participants are not told the results of their individual tests. But Martin said participating was about helping others as much as himself.

“It’s all part of being part of research that I’m passionate about to make the game better,” he said.