ESTANCIA, N.M. — The chorus of small voices ringing from a third-grade classroom on a recent morning signaled how far Estancia Elementary School had come in resuming a sense of normalcy after the latest coronavirus surge.

Students in the small, remote community of Estancia, N.M., were enthusiastically engaged in a vocabulary lesson, enunciating words with a “bossy r,” as well as homophones and homonyms, and spelling them on white boards.

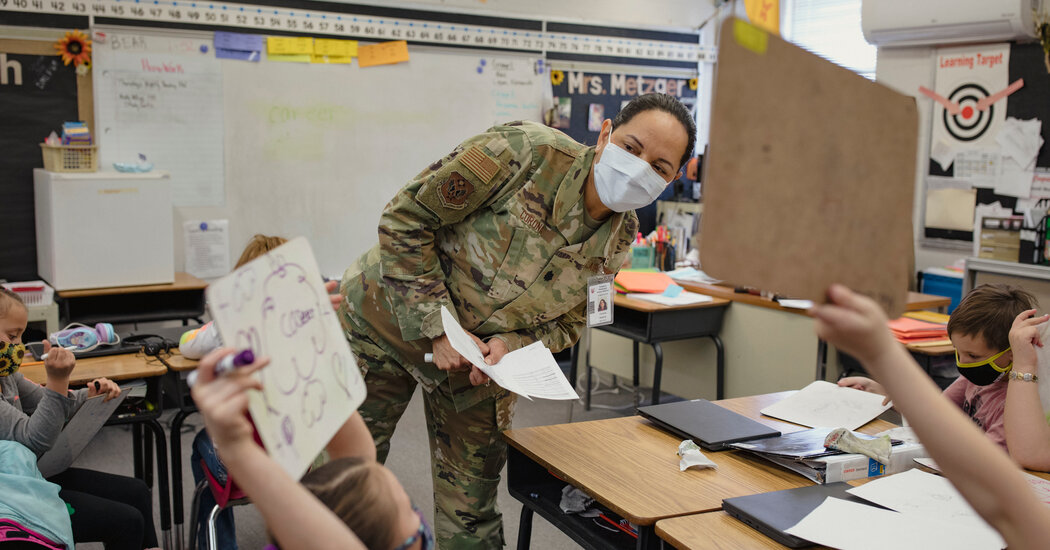

But there was also a sign of how far the district, about an hour outside Albuquerque, still had to go. The teacher moving about the classroom and calling on students to use the words in a sentence was clad in camouflage. “My substitute is wearing gear,” one student responded.

“Yes,” Lt. Col. Susana Corona replied, beaming. “The superintendent allows me to wear my uniform. I’m wearing a pair of boots.”

For the last month, dozens of soldiers and airmen and women in the New Mexico National Guard have been deployed to classrooms throughout the state to help with crippling pandemic-related staff shortages. Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham has also enlisted civilian state employees — herself included — to volunteer as substitute teachers.

New Mexico has been the only state to deploy National Guard troops in classrooms. But since the fall, when districts around the country began recruiting any qualified adult to take over classrooms temporarily, several other states have turned to uniformed personnel. National Guard members in Massachusetts have driven school buses, and last month, police officers in one city in Oklahoma served as substitutes.

The scenes of uniformed officers in classrooms have solicited mixed reactions. Some teachers see it as a slight against their profession, and a way to avoid tackling longstanding problems like low teacher pay. Other critics have worried that putting more uniformed officers in schools could create anxiety in student populations that have historically had hostile experiences with law enforcement.

But the presence of New Mexico’s state militia — whose members are trained to help with floods, freezes and fires as well as combat missions overseas — has largely been embraced by schools as a complicated but critical step toward recovery. Teachers have expressed gratitude for “extra bodies,” as one put it. Students were mostly unfazed but aware that, as Scarlett Tourville, a third grader in Colonel Corona’s class put it, “This is not normal.”

Superintendents were given the choice of whether to have the guardsmen and women wear regular clothes or duty uniforms; most joined Cindy L. Sims, the superintendent of the Estancia Municipal School District, in choosing the latter. “I wanted the kids to know she was here, to know why she was here,” Dr. Sims said. “I wanted them to see strength and community.”

For Dr. Sims, Colonel Corona’s presence breathed new life into a campus that had been scarred by death. In December alone, Dr. Sims attended seven funerals of people who died from Covid-19. Among them: the husband of a staff member who had contracted the disease at school and took it home, and a father who left behind a first-, seventh- and twelfth-grader. The week before Christmas, the district held a double funeral in the high school gymnasium for a father and grandmother of two students.

“Trying to have school at a time when everybody’s heart was broken was very difficult,” Dr. Sims said. “Our mission is to keep hope alive, and the National Guard is helping us do that.”

Colonel Corona, an intelligence officer in the New Mexico Guard, deployed to a number of states and countries during 10 years of active duty in the Air Force. She never envisioned that one of her missions would require being armed with a lesson plan, wet naps, and dry-erase markers.

But nor did she envision watching her own fourth grader try to learn from her teacher through a screen last year.

“You always have to be ready when there’s a need,” she said, “when there’s a call to service.”

Keeping the Doors Open

Staff shortages are the latest hurdle for school districts navigating a pandemic that is about to enter its third year.

Coronavirus-related illnesses, quarantines and job-related stress have hit many districts hard. But the country’s education leaders say the pandemic is just accelerating trends that were at least a decade in the making.

The National Education Association, the nation’s largest teacher’s union, published a survey this month that found 55 percent of educators were thinking about leaving the profession earlier than they had planned, up from 37 percent in August. Three-fourths of members said that widespread absences had required them to fill in for colleagues or take on other duties, and 80 percent reported that unfilled job openings had led to more work obligations.

“Crisis is the word we have to use now,” said Becky Pringle, the association’s president, describing the enlistment of the guard as a “stopgap.”

“We know just putting an adult in front of kids is not going to result in the instruction they deserve,” she added.

At Belen High School, in a farming community less than an hour south of Albuquerque, the staffing crunch has been felt acutely.

The high school reopened for in-person learning last spring. But by fall, it was short about a half-dozen teachers. One day there were 10 teachers out, and another six classes piled in the auditorium. Eliseo Aguirre, the principal, said he believed the death of a teacher from Covid had a chilling effect on teacher and substitute applications.

The arrival of Airman First Class Jennifer Marquez last month was a “blessing,” Mr. Aguirre said. On a recent Wednesday, she was covering a Spanish class — her third subject in two weeks.

“We’re going to use her every day until she gets orders that she has to go back,” Mr. Aguirre said, “which I hope isn’t until the end of the year.”

Veronica Pería, a freshman at Belen, was happy to see her, too. She said her grades suffered last semester, when her teachers were absent and random staff members were popping in and out of her classes, leading to inconsistent instruction. “It’s better than watching a video or something,” she said of having Ms. Marquez filling in. “It’s good to have someone I can go to and ask for help.”

Royceann LaFayette, a counselor at Belen, said the realities of New Mexico having among the country’s highest childhood poverty rates and lowest average teacher salaries had collided during the pandemic in a way she had not seen in her 29 years working in the state’s education system. State lawmakers just passed legislation that will raise teachers’ base salary by an average of 20 percent, starting this summer.

“The image that comes to mind,” she said, “is walking into a grocery store and seeing bare shelves.”

‘Semper Gumby’

When the call came from the governor, the New Mexico National Guard’s commander in chief, Brig. Gen. Jamison Herrera, knew he would have no trouble recruiting volunteers for Operation Supporting Teachers and Families (S.T.A.F.).

Many guardsmen and women had already seen how the pandemic affects students up close, having delivered meals to those at risk of going hungry when schools closed.

The Guard estimated that 50 of its members would volunteer; by this week, the state education department had issued licenses to 96.

The volunteers are on state active duty, paid through the state’s budget, similar to when they help with evacuations and search-and-rescue missions. Even those with the highest security clearances were required to go through the background check process and meet the same state licensing requirements as any other substitute applicant.

Although some members have advanced degrees, or certifications that could translate to the classroom — a welder is teaching shop class in one district, for example — General Herrera, a former teacher, impressed upon his team they were there to accomplish one goal.

“We are there to support the learning objectives of the teacher, because we certainly know we can’t fill their shoes,” he said.

Above all else, he told them, stay “Semper Gumby.”

To demonstrate how the unofficial military motto, meaning “Always Flexible,” could apply in the classroom, the Guard brought in Gwen Perea Warniment, the deputy secretary of teaching, learning and assessment for the New Mexico Public Education Department, to provide some quick training.

The Coronavirus Pandemic: Key Things to Know

“I wanted to highlight that the classroom was not going to be like the Guard; it’s going to be similar to a beehive — organized chaos,” she said.

She taught the basics of how to read a lesson plan, and what to do without one; classroom management strategies, like “1,2,3, eyes on me,” and how to approach a challenging student with curiosity, not combativeness.

Some of those lessons were on full display recently at Parkview Elementary School, in Socorro, N.M., about an hour south of Albuquerque in the Rio Grande Valley.

The Guard specifically sought volunteers to go to schools like this one, in hard-to-reach places, with hard-to-reach students. The school was shocked when Staff Sgt. Rainah Myers-Garcia reported for duty.

“When I saw the governor say it on TV, I thought there’s no way we’d get one because the big city schools get everything,” said Laurie Ocampo, the school’s principal. “And here she is, with a cape — or should I say, camo.”

Sergeant Myers-Garcia, a Guard member for 12 years, spent her first week with curious pre-kindergarteners reciting the names of food items and farm animals, and supervising recess with first graders who called her “Ms. Soldier” and asked her to babysit their dolls.

Her second week took her to a class of boisterous fifth graders who greeted her one recent day with, “Oh, you’re still here.”

The first day of that assignment was tough. The teacher’s absence was unexpected, so there were no lesson plans. She relied on Google searches to handle a fraction lesson, and stern warnings to get through the day.

“In their defense, their teacher’s not here and they have a soldier for a teacher,” she said.

The next morning, she arrived ready to be “Semper Gumby.” She had worksheets her mother had printed out for a morning icebreaker, a bag of prizes she had purchased from Wal-Mart, and two lesson plans she had borrowed from other teachers.

When she encountered the young man who had given her the most trouble the day before, she soothed his brewing tantrum by asking a simple question: Do you need help?

“We’re going to get through it, even if it’s painful,” Sergeant Myers-Garcia said. “I still prefer to be here than the kids not being in school.”

Colonel Corona has an open invitation to stay on as a substitute in Estancia. Dr. Sims, the superintendent, choked back tears when asked what will happen when her tour of duty ends. “It’s been a game-changer having Susana here,” she said. “You might think one isn’t enough; one was just enough.”

When Stephanie Romans had to spend five days in quarantine recently, the teacher of 37 years was apprehensive about her fourth-grade students falling behind.

But her fears eased when Colonel Corona called one night to ask it if was OK if she did not move on to a new math concept. She did not think the students fully grasped the one she had taught that day, she told Ms. Romans.

“I gave them a test on the math material when I got back and — boom — they did awesome,” Ms. Romans said.

Colonel Corona said she employed the same skills — command and confidence — that she did on any mission.

“I answered the call to service,” she said. “What this really should inspire is a greater respect for what teachers do every day.”

Adria Malcolm contributed reporting.