On an overcast late July day thick with humidity and dampening drizzles, I headed from Manhattan toward the Bulova Corporate Center, in Queens, in search of my ghost.

Until 2017, the Queens Museum had a satellite gallery at Bulova and organized artist exhibitions there. Denyse Thomasos’ show was one of them. A brilliant abstract painter from the Caribbean and Canada, Thomasos made audacious mural-size canvases that evoked an architecture of floating cities, prisons and slave ships. Then in 2012, on July 20, she suddenly died from an allergic reaction during a diagnostic procedure. She was 47.

Left behind somewhere at Bulova was a 1993 painting, “Jail,” purchased by Blumenfeld Development Group, owner of the building, and I was determined to find it with my colleague, David Breslin, with whom I was organizing the forthcoming Whitney Biennial. And so we found ourselves meandering through the hallways of this once Art Deco gem.

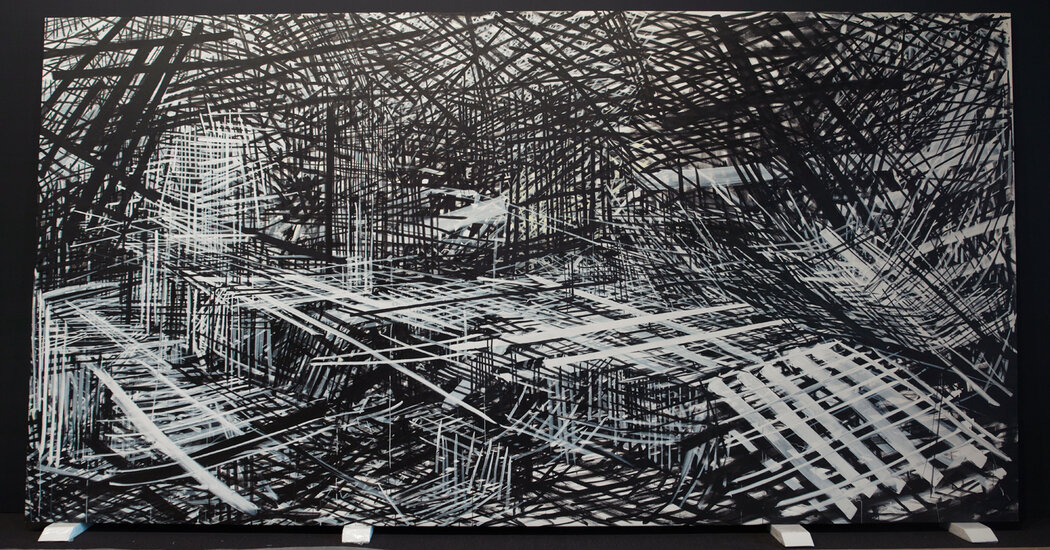

We found “Jail” sheathed in a plexiglass-fronted wood frame in one of the vestibules. As we approached the painting, its monumental scale loomed over us with Thomasos’ distinct visual lexicon, an intense use of densely overlapping black and white lines that achieved a sense of spatial distortion. For the artist, these cross-hatches were a means of recording time, like journal entries. Their concentrated, ligatured and rigorous application had a jarring effect: In order to truly behold the work, we had to step away from it, to distance ourselves.

“Jail” (1993) is one in a triptych of paintings made during the artist’s formative years, alongside “Displaced Burial/Burial at Gorée,” the first of her large-scale works, and “Dos Amigos (Slave Boat).” These works encapsulate the range of Thomasos’ social, political and historical missions and her intense research into the Middle Passage of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the impacts of immigration and the architecture of incarceration. All the while her paintings acknowledge the impossibility of ever being able to represent these histories and their aftermaths, by testing the capacity of abstraction to convey them.

As Thomasos explained in 2012 in a publication for an exhibition at the Janice Laking Gallery, “I used lines in deep space to recreate these claustrophobic conditions, leaving no room to breathe. To capture the feeling of confinement, I created three large-scale black-and-white paintings of the structures that were used to contain slaves — and left such catastrophic effects on the Black psyche: the slave ship, the prison, and the burial site. These became archetypal for me. I began to reconstruct and recycle their forms in all of my works.”

Thomasos lived in Philadelphia from 1990-1995, while teaching at the Tyler School of Art at the height of the crack-cocaine epidemic, which accelerated the precariousness of Black neighborhoods and instigated their collapse in several cities. During this time, she amassed data on the sharp increase of incarcerated people of color, as well as research on the Eastern State Penitentiary, a Quaker experiment in penal reform that set the model for solitary confinement from 1829 to 1971, and upon which her painting “Jail” is based.

This initial exploration would inspire her ongoing investigation of prison architecture, and later the industrial prison complex. “I noted the sleek architectural innovations and the vibrant, high-tech, constructivist color scheme,” she said of her painting process. “ The prisons indicate the complex weave of interdependence between the poor underclass and larger social and economic issues, which I translate in my interweaving lines.”

While Thomasos’ paintings refer to the systems and structures that shape our world, they are also deeply personal. The thick, opaque and accumulating forms also reference the sense of exile felt by her father, who died three months before she went to graduate school. In fact, “Displaced Burial” is thought to have been a memorial to him as much as to the enslaved housed on Gorée Island off Senegal before their departures to the Americas, where she had visited during her travels. She described her father as “a brilliant physicist and mathematician whom I saw suffer under racism in Canada. I thought of my father to be a compelling character, a typical immigrant story of hard work and, ultimately, the sacrifice of one’s own life for his family’s well-being and potential.”

An immigrant twice over, Thomasos was born in Trinidad in 1964, moved with her family to Toronto as a child in 1970, and to the United States in 1987. Her grandfather, Clytus Arnold Thomasos, was the first and longest serving Black speaker of the House in the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago, from 1961 to 1981.

She received a B.A. in art and art history from the University of Toronto in 1987 and an M.F.A. at the Yale University School of Art in 1989. Thomasos lived in the East Village with her husband, Samein Priester, and their daughter, Syann, until her untimely death in July 2012. She was a professor at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

While organizing the Biennial David and I had discussed the importance of mapping the connections between artists we were seeing and figures who had not received the recognition that they deserved. We opened the door to what we now lovingly describe as our “ghosts” with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, an American artist and writer of South Korean birth, as well as Steve Cannon, the poet and playwright who founded the interdisciplinary gallery and magazine A Gathering of the Tribes, and it was as if a clarion call went out. Others began to show up.

About a year ago, the curators Renée van der Avoird and Sally Frater invited me to give a keynote address at the Art Gallery of Ontario for a day of talks organized around Thomasos’ work, of which I was still unaware. My research brought me to the Queens Museum, to Thomasos’ current gallerist, Shelli Cassidy-McIntosh, and her predecessor, Jill Weinberg Adams.

I realized Thomasos was the one I have been waiting for — the one who viscerally captured, nearly 30 years ago, the unspeakable, irresolvable, the unimaginable, that which cannot be represented but perhaps only felt. As she said, “Overall I’m not trying to give the audience a happy experience or a dark experience. I’m trying to give a complex experience.”

Among her distinguishing qualities she helped align the identity-and-system-questioning conceptual art of David Hammons and Adrian Piper with the experimental abstract painting of Sam Gilliam, Ed Clark and Jack Whitten. She laid the groundwork for the artists Julie Mehretu and Ellen Gallagher, although neither of them knew of her or her work.

As if to quell any doubt I may have had, last May, when we finished installing Hammons’s public artwork “Day’s End” on Pier 52, he gave me a book titled “Quiet as It’s Kept.” Published in 2002 for an exhibition he curated in Vienna, it has in part informed the current Biennial title. (The colloquialism is also taken from the first line of Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” and is the title of the jazz drummer Max Roach’s 1960 album.) There were three artists in the Vienna show — Ed Clark, Stanley Whitney, and Thomasos. Clark and Whitney ultimately, after many years, fared well; few know about Thomasos.

Somewhere along the way I began to question who was really doing the haunting. Maybe I grappled with her art because I needed it. I needed her story, and maybe I needed some of the indelible fierceness for which she was known. It seems impossible to know why we are drawn to the things we come to desire other than their capacity to open us up. Those paintings touched me, delivered Thomasos and the themes of her work to me with the unsettling truth of their unending resonance and astounding presence.

Some of the unspeakable themes in her art do not always concern events of great magnitude. I would say the most unsettling one, the one that unmoors me — quiet as it’s kept — is what it means to have been unremarked upon. In the scale of her paintings she made herself incapable of being overlooked, undermined, or ignored, even to those who couldn’t fathom who she was or what she did. Not all confinements are physical. Some of the most violent ones, the ones you are forced to daily negotiate, are misogynistic and racist, especially in the instances when they intertwine.

Mr. Hammons and I had never spoken of Thomasos before. I felt the same particular and peculiar feeling when I received his book as I did when I first saw an image of “Displaced Burial.” I have only ever visited one slave castle — the very one on Gorée Island. It was as if Thomasos was speaking to me across time and space, buttressing her argument through the series of what at first seemed like coincidences — and as the universe swerved to show its boundless wisdom and our profound interconnectedness, she was finally heard.

Adrienne Edwards is a curator and director of curatorial affairs at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She is co-curator of the 2022 Whitney Biennial.