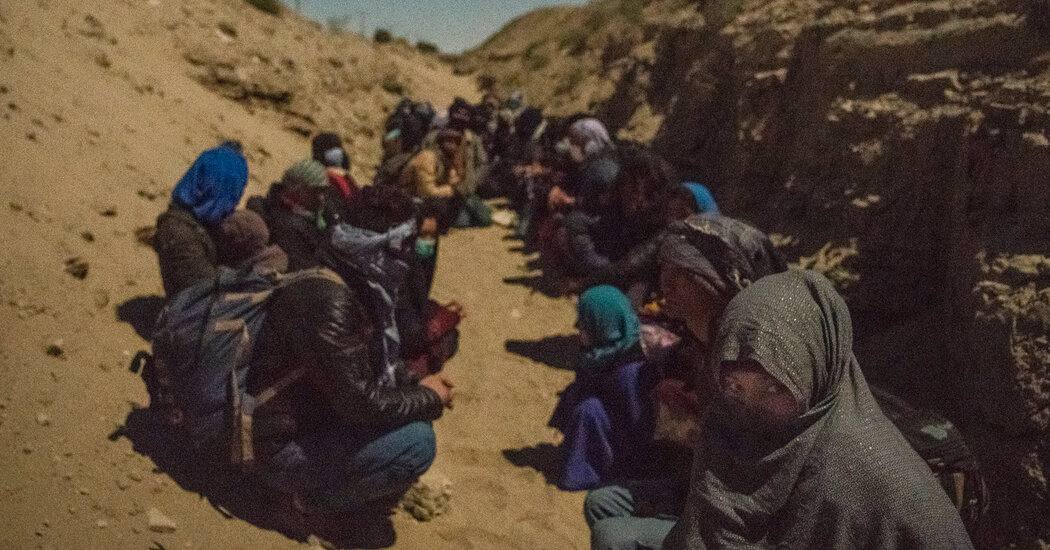

ZARANJ, Afghanistan — From their hide-out in the desert ravine, the migrants could just make out the white lights of the Iranian border glaring over the horizon.

The air was cold and their breath heavy. Many had spent the last of their savings on food weeks before and cobbled together cash from relatives, hoping to escape Afghanistan’s economic collapse. Now, looking at the border they saw a lifeline: work, money, food to eat.

“There is no other option for me, I cannot go back,” said Najaf Akhlaqi, 26, staring at the smugglers scouring the moonlit landscape for Taliban patrols. Then he jolted to his feet as the smugglers barked at the group to run.

Since the United States withdrew troops and the Taliban seized power, Afghanistan has plunged into an economic crisis that has pushed millions already living hand-to-mouth over the edge. Incomes have vanished, life-threatening hunger has become widespread and badly needed aid has been stymied by Western sanctions against Taliban officials.

More than half of the population is facing “extreme levels” of hunger, António Guterres, United Nations secretary-general, said last month. “For Afghans, daily life has become a frozen hell,” he added.

Now with no immediate respite in sight, hundreds of thousands of people have fled to neighboring countries.

From October through the end of January, more than a million Afghans in southwestern Afghanistan alone have set off down one of two major migration routes into Iran, according to migration researchers. Aid organizations estimate that around 4,000 to 5,000 people are crossing into Iran each day.

Though many are choosing to leave because of the immediate economic crisis, the prospect of long-term Taliban governance — including restrictions on women and fears of retribution — has only added to their urgency.

“There’s an exponential increase in the number of people departing Afghanistan through this route, particularly given how challenging this journey is in the winter months,” said David Mansfield, a researcher tracking Afghan migration. By his estimates, up to four times as many Afghans were leaving Afghanistan for Pakistan and then Iran each day in January compared with the same time last year.

Reporting From Afghanistan

The exodus has raised alarms across the region and in Europe, where politicians fear a repeat of the 2015 migrant crisis, when more than a million people, mostly Syrians, sought asylum in Europe, setting off a populist backlash. Many fear that this spring as temperatures rise and the snow-covered routes become easier to traverse, a deluge of Afghans could arrive at the European Union’s borders.

Determined to contain migrants in the region, the European Union last fall pledged over $1 billion in humanitarian aid for Afghanistan and neighboring countries hosting Afghans who have fled.

“We need new agreements and commitments in place to be able to assist and help an extremely vulnerable civil population,” Jonas Gahr Store, the Norwegian prime minister, said in a statement at the U.N. Security Council’s meeting on Afghanistan last month. “We must do what we can to avoid another migration crisis and another source of instability in the region and beyond.”

But Western donors are still wrestling with complicated questions over how to meet their humanitarian obligations to ordinary Afghans without propping up the new Taliban government.

In recent months, Taliban officials have appealed to Western officials to release their chokehold on the economy, making some promises around education for girls and other conditions set by the international community for aid. As the humanitarian situation worsened, the United States also issued some exemptions to sanctions and committed $308 million in aid last month — bringing the total U.S. assistance to the country to $782 million since October last year.

But aid can only go so far in a country facing economic collapse, experts say. Unless Western donors move more quickly to release their chokehold on the economy and revive the financial system, Afghans desperate for work will likely continue to look abroad.

Crouching among the migrant group in the desert, Mr. Akhlaqi steeled himself for the desperate dash ahead: A mile-long scramble over churned-earth trenches, a 15-foot-high border wall topped with barbed wire and a vast stretch of scrubland flush with Iranian security forces. Over the past month, he had crossed the border 19 times, he said. Each time, he was arrested and returned over the border.

A police officer under the former government, Mr. Akhlaqi went into hiding in relatives’ homes for fear of Taliban retribution. As the little savings that fed his family ran dry, he moved from city to city looking for a new job. But the work was scarce. So in early November, he linked up with smugglers in Nimruz Province determined to get to Iran.

“I’m afraid of the Iranian border guards,” he lamented. Still, he said, “I can’t stay here.”

Even before the Taliban takeover, Afghans accounted for the second highest number of asylum claims in Europe, after Syria, and one of the world’s largest populations of refugees and asylum seekers — around 3 million people — most of whom live in Iran and Pakistan.

Many fled through Nimruz, a remote corner of southwest Afghanistan wedged between the borders of Iran and Pakistan that has served as a smuggling haven for decades. In its capital, Zaranj, Afghans from around the country crowd into smuggler-run hotels that line the main road and gather around street vendors’ kebab stands, exchanging stories about the grueling journey ahead.

At a parking lot at the center of town known as “The Terminal,” men pile into the backs of pickup trucks bound for Pakistan while young boys hawk goggles and water bottles. On a recent day, their sales pitches — “Who wants water?” — were nearly smothered by the sounds of honking cars and the angry shouts of haggling men exchanging tattered Afghani bank notes for Iranian toman.

Standing in line to climb into the back of a pickup, Abdul, 25, had arrived the day before from Kunduz, a commercial hub in northern Afghanistan that was wracked with fighting last summer during the Taliban’s blitz offensive. As the thuds of mortar fire engulfed the city, his business sputtered to a halt. After the takeover, his shop stood empty as people saved the little money they had for basics like food and medicine.

As the months dragged on, Abdul borrowed money to feed his own family, plunging further and further into debt. Finally, he decided leaving for Iran was his only option.

“I don’t want to leave my country, but I have no other choice,” said Abdul, who asked that The Times use only his first name, fearing that his family could face retaliation. “If the economic situation continues like this, there will be no future here.”

As the economic crisis has worsened, local Taliban officials have sought to profit off the exodus by regulating the lucrative smuggling business. At the Terminal, a Taliban official sitting in a small silver car collects a new tax — 1,000 Afghanis, or about $10 — from each car heading to Pakistan.

At first, Taliban officials also taxed the city’s other main migrant route, a smuggler-escorted journey across the desert and over the border wall directly into Iran. But after accusations in September that a smuggler had raped a girl, the Taliban reversed course, cracking down on this desert route.

Still, such efforts have done little to deter smugglers.

Speeding through a desert road around midnight, one smuggler, S., who preferred to go by only his first initial because of the illegal nature of his work, blasted Arabic pop music from his stereo. A music video with a woman swaying in a tight black dress played on the car’s navigation screen. As he neared his safe house, he cut the back lights to avoid being followed.

Moving people each night requires a delicate dance: First, he strikes a deal with a low-ranking Iranian border guard to allow a certain number of migrants to cross. Then, he tells other smugglers to bring migrants from their hotel to a safe house in the desert and coordinates with his business partner to meet the group on the other side of the border. Once the sun sets, he and others drive for hours, scoping the area for Taliban patrols and — once the route is clear — take the migrants from the safe house to the border.

“We don’t have a home, our home is our car, all night driving near to the border — one day my wife will kick me out of home,” S. said, erupting in laughter.

Crossing the border is just the first hurdle that Afghans must overcome. Since the takeover, both Pakistan and Iran have stepped up deportations, warning that their fragile economies cannot handle an influx of migrants and refugees.

In the last five months of 2021, more than 500,000 who entered these countries illegally were either deported or voluntarily returned to Afghanistan, likely fearing deportation, according to the U.N.’s International Organization for Migration.

Sitting on the ragged blue carpet of one hotel was Negar, 35, who goes by only one name. She had climbed over the border wall into Iran with her six children two nights before desperate to start a new life in Iran. For months, she had stretched out her family’s meager savings, buying little more than bread and firewood to survive. When that cash ran out, she sold her only goat to make the journey here.

But once she touched Iranian soil, a pack of border guards descended on the group of migrants and fired shots into the pre-dawn darkness. Lying on the ground, Negar called out to her children and had a horrifying realization: Her two youngest sons were missing.

After two agonizing days, smugglers in Iran found her sons and sent them back to her in Zaranj. But shaken by losing them, she was at a loss over whether to attempt to cross again.

“I’m worried,” she said. “What if I can never make it to Iran?”