A man whose death sentence for killing a Missouri couple while robbing their home was overturned three times was scheduled to be executed on Tuesday.

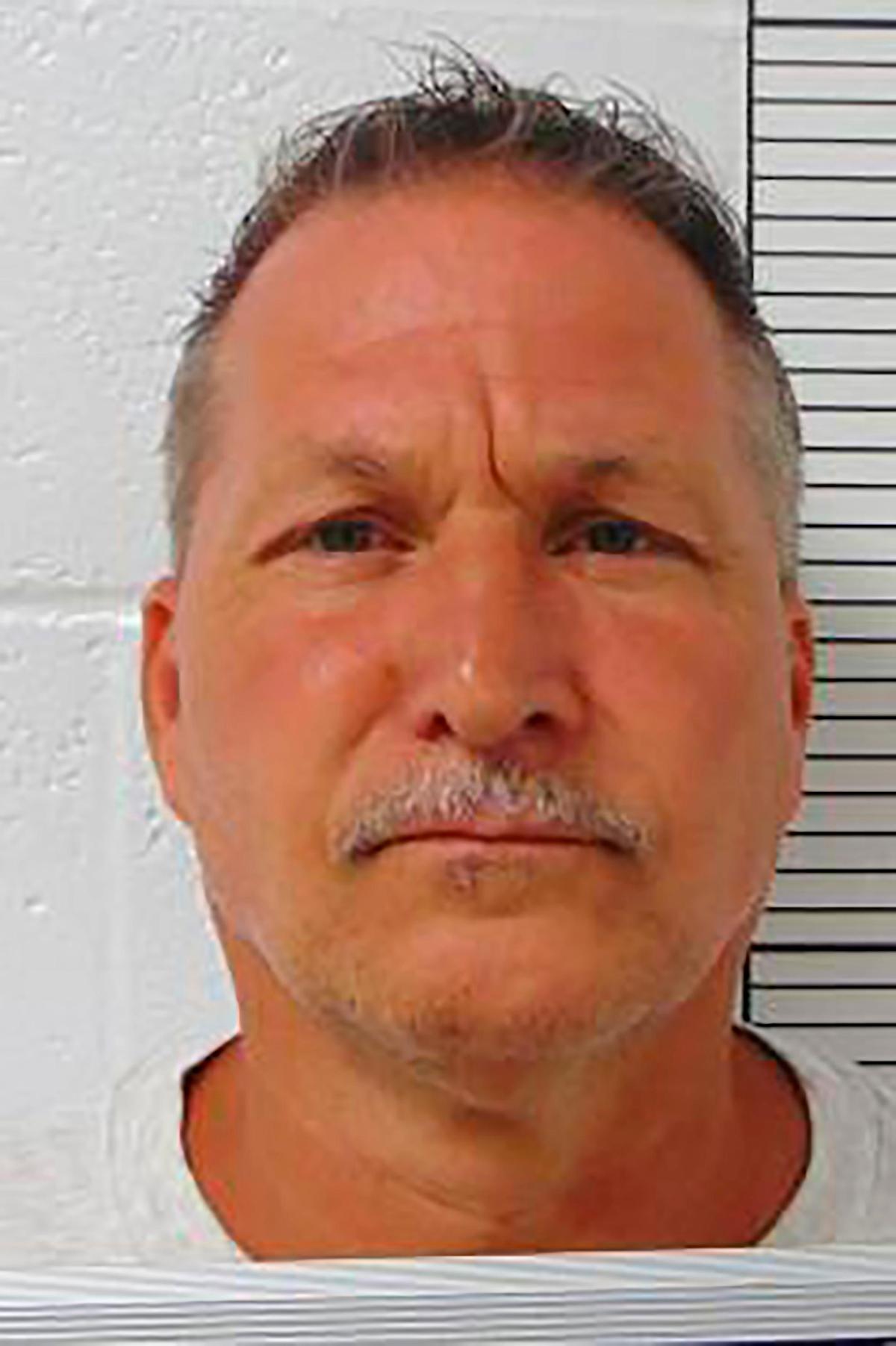

Carman Deck, 56, would be just the fifth U.S. inmate to be executed this year if his lethal injection goes ahead. His hopes for a reprieve were all but dashed on Monday when the U.S. Supreme Court turned aside an appeal and Republican Gov. Mike Parson declined Deck’s clemency request, though he could file new appeals.

Deck, who was from the St. Louis area, was a friend of the grandson of James and Zelma Long and knew they kept a safe in their home De Soto, about 45 miles (72 kilometers) southwest of St. Louis, according to court records.

In July 1996, Deck and his sister stopped at the home under the guise of asking for directions. Deck told a detective that he wasn’t surprised to be invited inside by the couple, who were in their late 60s.

“They’re country folks,” Deck said, according to court records. “They always do.”

Once inside, Deck pulled a gun from his waistband. At Deck’s command, Zelma Long opened the safe and removed jewelry, then got $200 from her purse and more money hidden in a canister.

Deck ordered the couple to lie on their stomachs on their bed. Court records said Deck stood there for 10 minutes deciding what to do, then shot James Long twice in the head before doing the same thing to Zelma Long.

A tip alerted police to Deck and he was arrested later that night outside his sister’s apartment building in St. Louis County. The decorative tin canister from the Long home was in his car.

Prosecutors said Deck later gave a full account of the killings. He was sentenced to death in 1998, but the Missouri Supreme Court tossed the sentence due to errors by Deck’s trial lawyer.

He was condemned to death a second time, but the U.S. Supreme Court threw out the sentence in 2005, citing the prejudice caused by Deck being shackled in front of the jury.

He was sentenced to death for a third time in 2008, but U.S. District Judge Catherine Perry overturned that sentence nine years later after she determined that “substantial” evidence arguing against the death penalty during Deck’s first two penalty phases was unavailable for the third because witnesses had died, couldn’t be found or declined to cooperate.

In October 2020, a three-judge panel of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals restored the death penalty, ruling that Deck should have raised his concern first in state court, not federal court. Appeals of that ruling were unsuccessful.

Deck’s clemency petition said he suffered sexual abuse and beatings as a child, and that he and his siblings were often left alone without food.

But Parson wasn’t swayed, explaining his rationale for rejecting the petition in a news release: “Mr. Deck has received due process, and three separate juries of his peers have recommended sentences of death for the brutal murders he committed.”

The number of executions in the U.S. has declined significantly since peaking at 98 in 1998. The drop has coincided with a decline in public support for capital punishment that has fallen from a high of 80% in 1994 to 54% in 2021, according to Gallup polls. Since the mid-1990s, opposition to capital punishment has risen from under 20% to about 45%.

Just four people have been executed in 2022 — Donald Anthony Grant and Gilbert Ray Postelle in Oklahoma, Matthew Reeves in Alabama and Carl Wayne Buntion last month in Texas. All four were convicted killers who were put to death by injection. Eleven people were executed in the U.S. last year, which was the country’s fewest executions since 1988.

Use of the death penalty has become concentrated mostly in a few Southern and Plains states. Last year, Texas executed three inmates, Oklahoma executed two, and one each were put to death in Alabama, Mississippi and Missouri. Three federal inmates were executed in January 2021, toward the end of President Donald Trump’s administration.

On Monday, Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee paused executions for the rest of the year to enable a review of lethal injection procedures after a testing oversight forced the state to call off the execution of Oscar Smith an hour before he was to die on April 21.