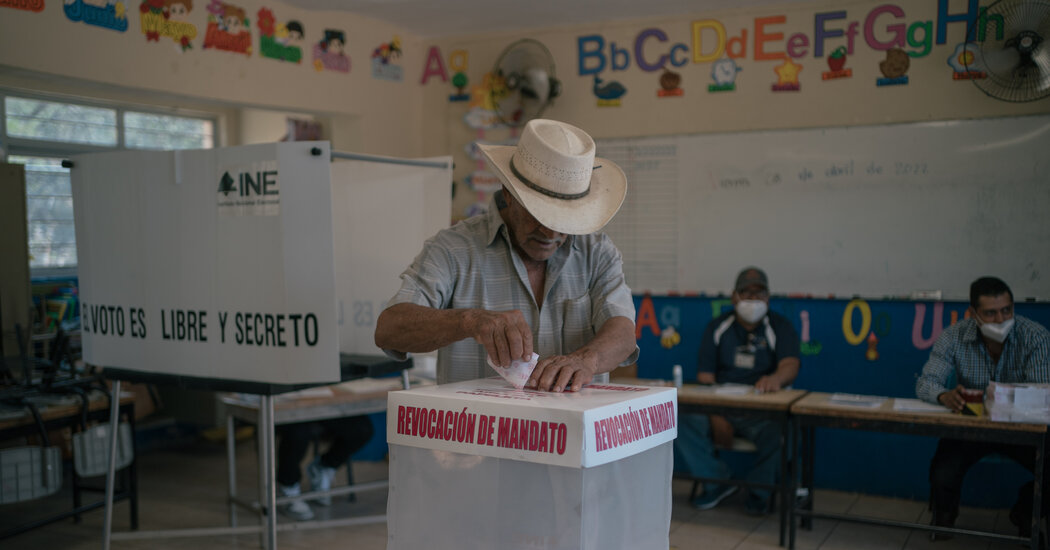

MEXICO CITY — Pitched by the president as a landmark exercise for Mexico’s democracy, Sunday’s recall referendum gave voters the chance to remove their head of state from office for the first time.

But with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s popularity still high and the opposition largely boycotting the event, the results of the referendum were almost assured.

Instead, like so much in the country’s polarized politics these days, the vote became one more trench from which each side of the political spectrum could do battle.

On Sunday, almost 18 percent of the electorate cast their ballot, far less than was needed for the result to become binding, making the outcome largely symbolic.

But more than 90 percent of those who did turn out voted in favor of the president completing his six-year term, according to preliminary results from Mexico’s electoral watchdog.

Coming out of the referendum, the president and his backers will be able to point to the overwhelming support for Mr. López Obrador and his political project among his base, even at a moment of weakness. The president has struggled to follow through on key campaign promises, with his approval rating slipping to 59 percent last month from 66 percent in December, according to a poll from El Economista newspaper.

Although Mr. López Obrador fell far short of the 40 percent participation required to make the results count, marshaling more than 15 million people across the country to vote in his favor underscores his ability to mobilize his base at a time when his government’s achievements are under scrutiny.

“More than 15 million Mexicans are happy and want me to continue until September 2024,” Mr. López Obrador said in a video message published shortly after preliminary results were announced. “We are going to continue with the transformation of our country.”

With the next presidential election about two years away, the recall referendum also presented an opportunity for Mr. López Obrador to test his party’s strengths and weaknesses across the country, and determine who might be best positioned to succeed him. Mr. López Obrador is limited to one six-year term by the Constitution, but as his party’s key power broker, he is expected to play a vital role in picking a successor to carry on his legacy.

On the other side, the opposition viewed the exercise as an attempt to shore up the president’s hold on power. The president’s critics pointed to the low overall turnout as anything but a mandate for Mr. López Obrador and his efforts to transform the country.

“It has been a total failure,” said Juan Romero Hicks, a congressman with the opposition National Action Party in a video message posted shortly after polls closed. “Our president lost because he doesn’t have the confidence of the people.”

Analysts said that the vote, which was executed smoothly, may actually end up bolstering the image of one of the president’s most frequent targets: Mexico’s electoral watchdog.

In the months leading up to the vote, Mr. López Obrador and his supporters lobbied a barrage of criticism at the agency for not doing enough to promote the referendum and for not setting up enough ballot boxes.

“The I.N.E. is keeping quiet in an attitude that is totally undemocratic and contrary to the Constitution,” Mr. López Obrador said at a recent news conference ahead of the referendum, using the institute’s Spanish initials. “They are hiding” the ballot boxes, he added.

The institute’s request for more funding from the federal government to oversee the vote was rejected. So, with a budget that was about half as much as what it said it needed, the watchdog set up far fewer ballot boxes than it would have in a presidential election.

“It’s a strategy to put the I.N.E. in a situation where it cannot fulfill its duties,” said Lorenzo Córdova, the leader of the electoral agency. “It’s a trap.”

But while turnout was low, it was stronger than some analysts had expected, which may strengthen the institute’s reputation and insulate it from further attacks from the president and his party.

“The undisputed winner, beyond the war of figures and narratives, is the I.N.E.,” said Carlos Bravo Regidor, a political analyst.

The fact that more than 16 million people turned out to cast their ballots could also work in the president’s favor, analysts said.

“It surpassed expectations,” said Blanca Heredia, a professor at CIDE, a research institution based in Mexico City. “I think it was a very good turnout, taking into account very unfavorable conditions for people to vote: there was no clear opponent, there was no competition.”

She added: “It was almost like a symbolic battle.”

The referendum is typical of Mr. López Obrador’s governing style. The president has spent much of his term in campaign mode, traveling the country to meet with voters and keep his base energized. In the lead-up to the 2024 elections, the recall vote has served as an opportunity to fire up his base in key battlegrounds.

There is a particular focus on Mexico City, long considered the president’s stronghold. The city’s mayor, Claudia Sheinbaum, a member of his party, is widely assumed to be among the likeliest contenders for the nation’s top job after Mr. López Obrador’s term is up. But last year, the party lost several critical seats in the capital’s legislature while Ms. Sheinbaum was running the city, which was seen as a potential blow to her political future.

Although the nation’s Supreme Court has said political parties cannot advertise the recall, Ms. Sheinbaum had spent weeks furiously campaigning in support of the vote, which was seen as a chance for the mayor to recover from the party’s losses last year.

But as the initial results began rolling in, it became clear that Ms. Sheinbaum’s efforts seemed to have fallen short: Despite ubiquitous advertising and consistent promotion from the mayor, the participation rate in Mexico City was not among the top five states.

The final outcome may yet alter the political mood in Mexico, showing the president and his party which parts of the country, and which potential successors, will be most important to securing the presidency in 2024.

But far from the seismic shift that a recall referendum of a president might have brought, this vote appears to have merely underscored the acrimony of Mexican politics. With the low turnout rendering the results nonbinding, the country’s polarized political forces will instead be left to fight over the narrative that emerges from the results to try to bolster their competing claims to power.