Millions of dollars of public funds allegedly stolen by two of Kenya’s richest men are being returned to the country to buy life-saving Covid-19 equipment following a landmark agreement.

The deal with Jersey, a self-governing island in the English Channel, has been hailed as “a victory for the people of Kenya” by its High Commissioner in the UK, Manoah Esipisu.

The entangled web of connections that eventually ended in this deal first emerged following a divorce case.

Back in 2006, Samuel Githuru, the wealthy boss of Kenya’s power company, and his wife Salome Njeri were divorced.

When it came to splitting up their assets, Ms Njeri felt she was not getting her fair share.

She alleged some of her husband’s assets were being hidden from the proceedings and, in court, listed details of accounts she said belonged to Mr Githuru in Jersey, which is often associated with secretive offshore banking and a low-tax environment.

That sparked a nine-year investigation by the Jersey authorities across 12 jurisdictions.

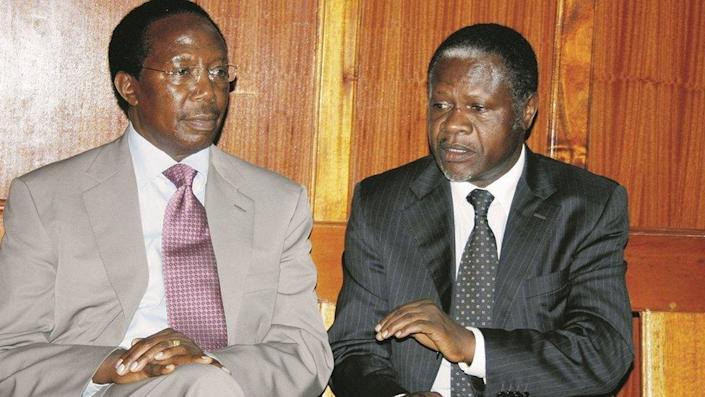

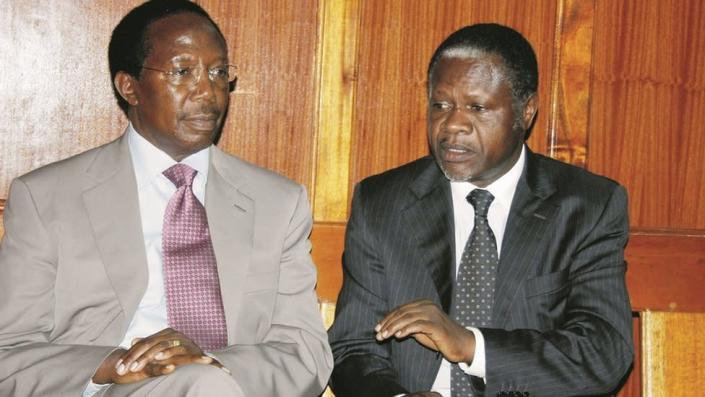

As part of that investigation, in 2011, they accused Mr Githuru and former Finance Minister Chris Okemo of taking kickbacks from multinationals which were sent to a Jersey-registered company.

The Jersey authorities issued arrest warrants for both men and have been waiting for their extradition from Kenya ever since.

The economic crimes they were accused of included a deal with a Finnish firm to construct a power station near Mombasa, Kenya’s second largest city, and taking millions of pounds in kickbacks from British, Norwegian and German engineering firms, as well as a US communications giant.

Despite repeated attempts to contact them by the BBC, both men and their lawyers would not comment on the allegations levelled against them.

However in 2016, the Jersey-registered company Windward Trading Limited pleaded guilty to four counts of money laundering in a Jersey court.

The court ruled that the company, whose ultimate owner was Mr Githuru, should be stripped of more than $4.9m (£3.6m) in assets for money laundering.

It is the majority of this money that allegedly came from corrupt activities in Kenya between 1999 and 2002 that is now being returned to the country.

That was made possible by a 2018 agreement signed in Kenya by then UK Prime Minister Theresa May, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and the Swiss and Jersey governments.

In the deal, it was established that allegedly stolen assets could be returned to Kenya, provided they were used exclusively for development projects.

This arrangement, known as the Framework for the Return of Assets from Corruption and Crime to Kenya (Fracck), was hailed by the UN as “innovative” and “novel”.

It gives the Jersey authorities a licence to unfreeze money they believe was stolen and send it back before those accused of stealing it go on trial.

“The question for us [in Jersey] was: should we wait for a convoluted judicial process based on the actions of two individuals, which… have been shown to be illegal in the Jersey court? Or should we allow the money to return for the benefit of the citizens of Kenya?” Senator Ian Gorst, Jersey’s Minister for External Relations, explained.

The handing over of Mr Githuru’s allegedly stolen millions back to ordinary Kenyans is Fracck’s first test.

Spending it in a transparent and accountable way is the job of Crown Agents, the not-for-profit international development company.

Its boss Fergus Drake told the BBC that he was in contact with Kenya’s health ministry to assess what was needed in the fight against Covid-19.

He said it wanted “specific lab equipment to test for Covid-19” and ancillary equipment “like micro-tubes, PCR tests, and other kit”.

Mr Drake expects to deliver the vital equipment to half a dozen hospitals in around two months, subject to supply chain bottlenecks.

He said boosting testing would allow Kenyans to better manage the pandemic and know which areas are in urgent need of vaccines.

At present, less than 20% of Kenyans are fully vaccinated.

Mr Drake acknowledged that the sum of money which he is disbursing – $3.5m – will not go “that far” in terms of a country’s response to Covid-19, but he hoped this type of “targeted” help will have an “exponential impact” against the virus.

Campaigners believe that the Fracck is a model for a new way that ill-gotten gains can be returned.

The UK is also a signatory to another agreement – the UN Convention against Corruption – so is obliged to return criminal funds where conditions to do so are met.

But according to Steve Goodrich, head of research and investigations at Transparency International (TI) UK, returns from the UK often do not go directly to development projects.

He pointed to the return of money laundered by former Nigerian Delta state Governor James Ibori in 2012 which was given to the federal government there. And he was concerned that repatriated funds could get lost to corruption.

So Mr Goodrich said this case was “a step in the right direction”.

But, he added, to have “a credible deterrent” against those looking to stash their stolen money in the UK, he said the government “really needs to up its game” on asset recovery.

For example, he said the UK should start by looking at what he believed was “over £5bn-worth of British property bought with suspect funds”.

This episode also focuses attention on Kenya’s fight against corruption at home.

The country is ranked 128th in the world in TI’s perceptions of corruption index, with public officials and business people open to bribery.

There are just months left before President Kenyatta is due to stand down, having pledged to make fighting corruption part of his legacy.

As part of that, politicians and public officials are currently being asked to declare their wealth, with anti-corruption auditing in place.

Kenya’s High Commissioner, Mr Esipisu, who was once the president’s spokesman, told the BBC the Fracck agreement was a “huge contribution” to the president’s agenda as it sent a signal that “corrupt people will not be safe simply because they hide their money abroad”.

He added, passionately, that “these are funds stolen from Kenyans, looted from Kenyans, and with this agreement, these funds are being returned to assist the Kenyan people for whom they were meant in the first instance. So this is a victory for the Kenyan people.”

With the funds now on their way from Jersey to Kenya, the focus turns to the possible extradition from Kenya to Jersey of the two accused men.

At the beginning of February, extradition proceedings finally got under way in Nairobi’s City Magistrates’ Court, after a 10-year legal battle over whether the government’s chief legal officer or the public prosecutor should be leading the case.

Kenya’s department for public prosecution is now in charge of the process and its Deputy Director Victor Mule said the next hearing was expected in May.

He believed it would not take another 10 years to resolve.

Mr Githuru’s lawyer chose not to comment on the ongoing legal process when contacted by the BBC.

Jersey Senator Mr Gorst concedes there were shortcomings which allowed this allegedly stolen money to enter the island in the first place.

He warned any future perpetrators that its regulations had been tightened but that any ill-gotten funds which did get through would be located and “we will return it to the citizens to whom it belongs”.