The winner of Kenya’s presidential election on 9 August will face a host of difficult political and economic issues when he takes office. Here, in charts, we explain some of the things on the minds of voters as they cast their ballots.

The next president may have to come up with a way to help people afford some essential goods.

Kenyans, like others around the world, have been finding that their money is not going as far as it used to when it comes to buying the basics.

In June, annual inflation was 7.9%, but the increase in the price of some key food items, including maize flour and cooking oil, was much higher. To ease the problems the outgoing government of President Uhuru Kenyatta subsidised the cost of maize flour in July, but it is not clear if this policy will be continued.

And with an ongoing drought affecting three million Kenyans, many are struggling to afford any food at all.

The government has also been subsidising the price of petrol to keep that more affordable. But this policy comes at a big cost – $141m (£120m) in July – potentially adding to the huge debt the country owes.

This has been skyrocketing under the presidency of Mr Kenyatta, and now amounts to some 68% of GDP. The government borrowed to pay for big infrastructure projects like the Chinese-built railway linking the capital, Nairobi, to the coast.

Investment in infrastructure can aid long-term economic growth but the sums involved are huge – the railway cost $3.2bn.

A large amount of the money is owed to Chinese banks. The government spends about half its revenue paying back the debt and the interest it has accrued.

More than three-quarters of Kenya’s population are under 35 and a big chunk of those are of voting age.

Addressing the concerns of young people could be a significant vote winner.

The lack of formal employment is a big issue. Many between 18 and 35 have no job at all despite having degrees or other suitable qualifications.

The large number of under-18s suggests that boosting investment in education needs to be a priority.

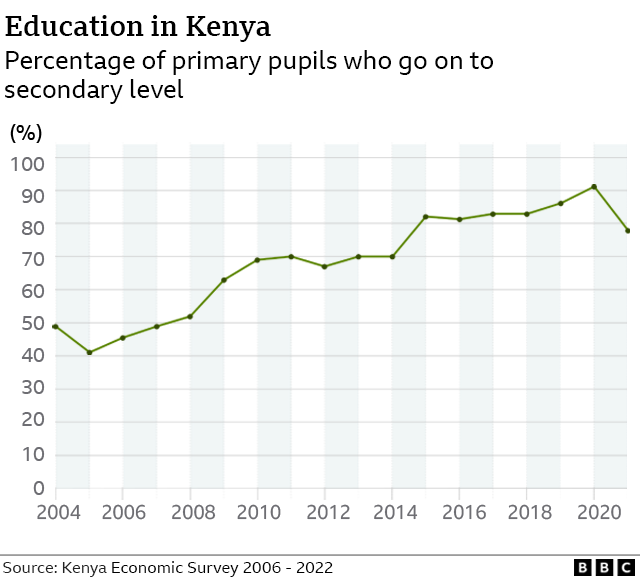

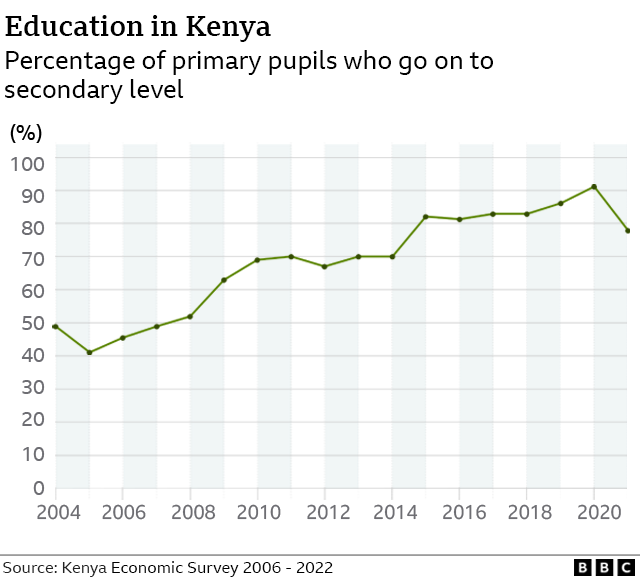

In recent years, Kenya has been successful in improving performance in education.

The government introduced free primary school education in 2003, which led to many more children going to school.

An increasing proportion have gone on to secondary school, which, since 2008, has been subsidised.

Nevertheless, one in five secondary pupils in Kenya do not graduate.

Many parents still prefer to pay for their children to go to what they see as better-quality, privately-run schools.

Another key factor in how people will vote is likely to be ethnicity.

It is assumed that the two main candidates, Raila Odinga (a Luo) and William Ruto (a Kalenjin), will get many of the votes of their respective ethnic groups.

But this is the first Kenyan election in the multiparty era where none of the front-runners are from the biggest group, the Kikuyu.

Both main candidates are aware of the need to attract this key constituency and have chosen Kikuyu running mates.

The violence that followed the 2007 election was driven by ethnicity but 15 years on there is an argument that it is becoming less significant in determining how people vote.

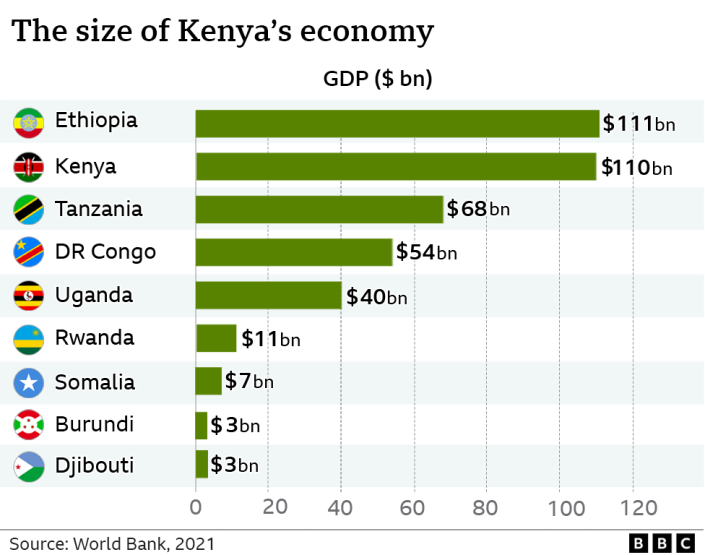

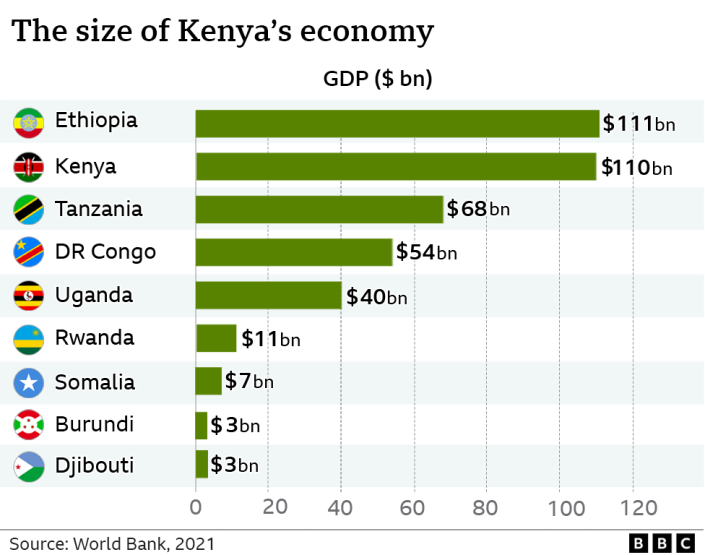

Kenya is a regional economic giant and what happens there affects the rest of East Africa.

In recent years it has lost ground to Ethiopia, but if you look at the average income per person in Kenya then, at just over $2,000 a year, it is more than double its northern neighbour.

However, this crude figure, estimated last year, masks the huge inequalities in the country and may not include the full impact of the shutdowns introduced in response to the Covid pandemic.

Kenya’s regional dominance is also reflected in the proportion of people who have access to electricity and the internet.

The figures however show that nearly three out of every 10 Kenyans do not have power and the large majority do not have internet access.

Improving these indicators will be a measure of success for whoever wins the presidency.