Russian President Vladimir Putin’s “partial mobilization” of some 300,000 reservists to bolster withering Russian forces in Ukraine was not a popular move. Cities around Russia saw their biggest anti-war protests since Putin launched his invasion in late February, and panicked Russian men rushed to the border or scrambled to buy the remaining exorbitantly priced airplane tickets to the few destinations still welcoming Russians.

“Google search trends showed a spike in queries like ‘how to leave Russia’ and even ‘how to break an arm at home,’ raising speculation some Russians were thinking of resorting to self-harm to avoid the war,” The Washington Post reports.

Russian pro-war nationalists, meanwhile, wanted universal conscription, but “even this limited mobilization is likely to be highly unpopular with parts of the Russian population,” Britain’s Ministry of Defense assessed Thursday. “Putin is accepting considerable political risk in the hope of generating much needed combat power. The move is effectively an admission that Russia has exhausted its supply of willing volunteers to fight in Ukraine,” the Defense Ministry added, and the new muster of conscripts is “unlikely to be combat effective for months” or numerous enough to reverse Russia’s flagging fortunes.

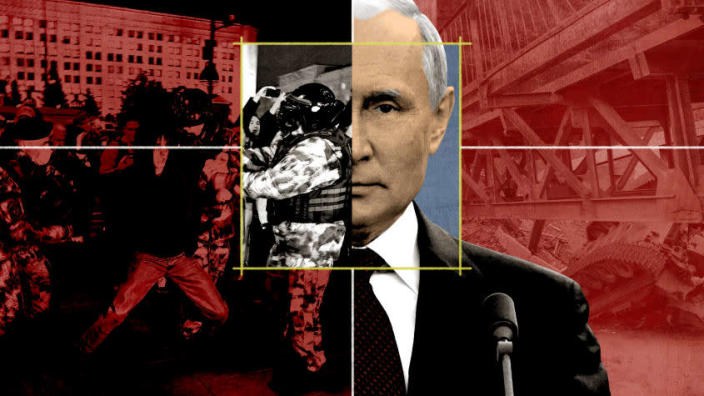

Putin has built up an iron grip on power over his two decades leading Russia. Could Ukraine end up being his Waterloo?

Putin will lose this high-stakes gamble

Putin “asking young men to commit their lives to a flagging war effort is risky — not only because it might not bring benefits on the battlefield, but because it is likely to provoke many of those men into outright opposition to the war itself,” Samuel Greene, professor of Russian politics at King’s College London, writes in The Washington Post. “For the war’s opponents, on the other hand, appealing to young married men looks like the clearest route to stymying Putin’s plans.”

Public opinion won’t tumble right away, says R.Politik political consultant Tatiana Stanovaya. “Mobilization will be gradually expanded. Society will slowly become irritated and indignant — do not expect mass protests, but rather waves of indignation,” she tells the Financial Times. “This is the erosion of Putin’s power in its purest form.”

Putin’s partial mobilization was the “careful balancing act of a leader under pressure, who is trying to: 1. please hardliners and Russian milbloggers; 2. not displease the general populace; 3. appease the military; [and] 4. give the impression he is not losing a war,” says retired Australian Maj. Gen. Mick Ryan. But what it really tells us is “Putin and his military privately accept that they could lose this war,” and his “gamble here” just “prolongs the agony of the Ukrainian people without providing any real chance of a Russian victory.”

Be careful what you wish for

“The whole world should be praying for Russia’s victory, because there are only two ways this can end: either Russia wins, or a nuclear apocalypse,” nationalist Russian tycoon Konstantin Malofeyev tells the Financial Times. “If we don’t win, we will have to use nuclear weapons, because we can’t lose,” he added. “Does anyone really think Russia will accept defeat and not use its nuclear arsenal?”

The cut is probably not deep enough to rock Putin’s standing

“Putin’s latest escalation in Ukraine is no show of strength,” and it will probably only “mollify his hard-line critics in Russia for a while,” The Wall Street Journal said in an editorial. But as “Putin’s announcement shows, the war isn’t over,” and his partial call-up “falls far short of the full war footing, or a military draft, that would enlist the sons of Moscow and St. Petersburg elites” and clarify for Russians that they can lose “far more than the chance to eat at the now shuttered McDonald’s.”

“Over the past six months, an adaptation has taken place to the new conditions, people calmed down,” Denis Volkov, director of Moscow pollster Levada Center, tells the Financial Times. The partial mobilization may agitate people again, and “I think if the Kremlin could have avoided it, it would have,” he added. “But the conflict has its own logic, and it has led them to take an unpopular decision.”

And we don’t know this mobilization won’t work out for Putin, notes Michael Kofman, chief Russia analyst at CNA. “It won’t solve many of the [Russian] military’s challenges in this war, but it could alter the dynamic” and “extend Russia’s ability to sustain this war,” he added. “Fair to say that these are uncharted waters, and so we should take care with deterministic or definitive claims.”

And he can always pin the blame on someone else

Putin’s gamble that he can stanch the bleeding with, at most, 300,000 poorly trained and equipped unwilling conscripts won’t work, but he “will likely wait to see if these efforts are successful before either escalating further or blaming his loss on a scapegoat,” the Institute for the Study of War writes. “His most likely scapegoat is Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and the Russian Ministry of Defense,” and the fact that he had Shoigu lay out the details of the mobilization suggests he “intended to make Shoigu the face of the current effort.”

Interestingly, in his speech, Putin “doesn’t describe it as his order, rather ‘I find it necessary to support the proposal of the Defense Ministry and the General Staff on partial mobilization,'” notes Australia’s Ryan. “This sets up the military for eventual blame in the war.” But at the same time, “the partial mobilization is unlikely to appease hardliners and will probably scare the general population,” he adds. “Perhaps this is why airfares out of Russia are selling so quickly.”

Putin is in deep trouble, and not just from the mobilization

Putin’s decision to swap leaders of Ukraine’s Azov Battalion for Viktor Medvedchuk, a Ukrainian businessman and politician who’s a close friend of Putin, “is an even bigger blow to Russian nationalists than the Kharkiv retreat,” Belarusian journalist Tadeusz Giczan writes. “The retreat could be explained by the mistakes of the military, while the release of the Azov command undermines the very idea of ‘denazification,'” which was Putin’s rationale for invading in the first place.

Andriy Yermak, a top adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, said Ukraine traded Medvedchuk and about 54 other prisoners or war for 215 Ukrainian POWs, including 108 members of the Azov Battalion that defended Mariupol against overwhelming odds for 80 brutal days. “Zelensky gave a clear order to return our heroes. The result: our heroes are free,” Yermak said. “We exchanged 200 of our heroes for Medvedchuk, who had already given all the testimony he could.”

“One of the main aims of denazification was the elimination of Azov, and the fall of Mariupol and their capture was the main triumph of the war to date,” Giczan argues. “Their trial and execution were supposed to be the culmination of the ‘liberation’ of Ukraine. And then suddenly, when the cages for the tribunal were ready, they are swapped for the father of Putin’s goddaughter.”

Between Putin “making it clear to everyone that the idea of ‘denazifying Ukraine’ was just a bluff” and destroying “Russia’s main social contract of the last 30 years — you let us get rich and we stay out of your private life” — with his mobilization, Giczan writes, anger will spread from activists to “a huge apolitical part of the population, something completely unprecedented. It’s still too early but I’m pretty sure future historians will mark 09/21/22 as one of the key days in the fall of Putin’s Russia.”

You may also like

Trump claims on Fox News that presidents can declassify documents ‘by thinking about it’

Bachelorette star DeMario Jackson accused of sexually assaulting 2 women

The Space Force unveils its official anthem, ‘Semper Supra,’ and people don’t love it