The recent arrests and incarcerations of Iranian directors Mohammad Rasoulof, Mostafa Al-Ahmad and Jafar Panahi — all of whom have been locked up in Tehran’s notorious Evin Prison in the space of less than a week — have been prompted by escalating tensions between the hard-line government of Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi and the West, according to experts.

“The government in Iran is sending a message to all of us around the world saying, ‘Things are getting worse,’ and this appears to be part of the nuclear deal negotiations and the geopolitical repercussions of what’s happening after the Russian invasion of Ukraine,” says Syrian multi-hyphenate Orwa Nyrabia, chair of the Berlin-based International Coalition for Filmmakers at Risk (ICFR), who is in close contact with the detained directors.

Talks to revive Tehran’s 2015 nuclear accord with world powers have ground to a halt partly due to the fact that Russia is balking, since lifting sanctions could free up million of barrels of Tehran’s crude oil stocks for global consumption, giving Russia less leverage as a major oil and gas supplier to the world, political analysts say.

Along with the dissident filmmakers, Iranian authorities last week arrested a reformist politician, Mostafa Tajzadeh, who has been critical of the government. Several foreigners have also landed in Iranian prison in recent weeks, including two French citizens, a Swedish tourist and a Polish scientist, the Associated Press has reported, prompting concerns that Iran is trying to leverage all these arrests as bargaining chips in the negotiations.

Nyrabia, who also heads the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), points out that Iran’s ongoing crackdown on its film community also comprises internationally known Iranian doc directors Mina Keshavarz (“The Art of Living in Danger”) and Firouzeh Khosravani (“Radiograph of a Family”), both arrested in their Tehran homes in May and subsequently released on bail but banned from traveling, despite no charges being filed.

He notes that over the years, when the West and Iran were at loggerheads, “these [directors] were the people who were breaking the barrier and making everyone in the world connect with Iranian culture and find empathy and identification with the people and society in Iran.”

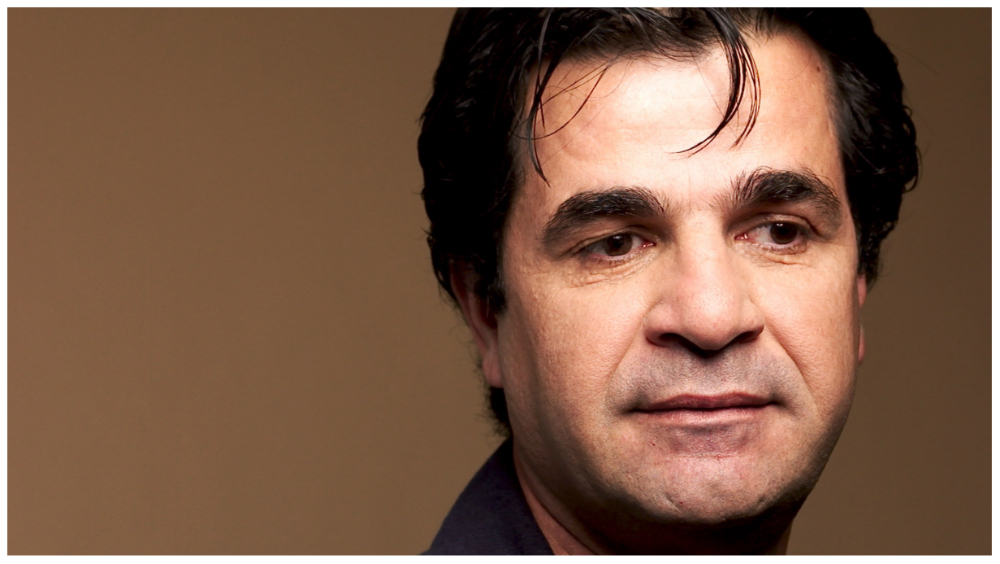

Rasoulof, who won the 2020 Berlin Golden Bear for “There Is No Evil” — which consists of four connected episodes centered on the death penalty and repression of personal freedom in Iran — is among the country’s most prominent directors, even though his films are banned in Iran.

Rasoulof and his frequent collaborator, the director Al-Ahmad, were detained last Friday for posting an appeal urging Iranian security forces to stop using weapons using the hashtag #put_your_gun_down following protests in May in the southwestern city of Abadan where there were clashes with police. The uproar was prompted by a building collapse that resulted in 41 people being killed.

The appeal against police violence for which Rasoulof and Al-Ahmad have been arrested was signed by at least 70 other members of Iran’s film community, including Panahi according to reports.

Panahi, who is among Iran’s best-known directors, known globally for prizewinning works such as “The Circle,” “Offside,” “This is Not a Film,” and 2015 Berlin Golden Bear winner “Taxi” — in which he thumbs his nose at censorship, poverty and the oppression of women in Iran — went to the prosecutor’s office in Tehran on Monday out of solidarity to inquire about the cases of his two incarcerated fellow filmmakers. He was jailed on the spot.

In 2011, both Rasoulof and Panahi where sentenced to six years in prison and a 20-year ban on filmmaking on vague charges of “propaganda against the system.”

Rasoulof’s sentence at the time was later suspended and he was released on bail. After 2014, the climate for filmmakers improved during the mandate of more progressive Iranian president Hassan Rouhani. Rasoulof and Panahi have continued to make films without government permission that have been released internationally to great acclaim.

But now a more conservative backlash is being unleashed under the government of Raisi, who took office in Aug. 2021, and has been crushing dissent as it faces escalating unrest amid the country’s growing economic crisis.

“Unable or unwilling to tackle the many severe challenges facing Iran, the government has resorted to its repressive reflex of arresting popular critics,” said Tara Sepehri Far, senior Iran researcher at Human Rights Watch, in a statement. “There is no reason to believe these recent arrests are anything but cynical moves to deter popular outrage at the government’s widespread failures,” she noted.

Half a dozen Iranian film personalities declined to be interviewed for this article for fear of reprisal.

Meanwhile, top film festivals around the world, including Berlin, Locarno, Venice and Cannes, have issued statements condemning the recent arrests of the three filmmakers and “the wave of repression obviously in progress in Iran against its artists,” as a Cannes statement put it.

Said Nyrabia: “We know that these appeals are being heard, and that it is essential that anyone who prosecutes these filmmakers doesn’t forget that this is a very visible act.”

He added: “We still have hope that President Raisi realizes that they should not burn down the last bridges. And Iranian filmmakers are the last bridges.”