A bipartisan majority of Ohio Supreme Court justices has ratcheted up an extraordinary legal standoff over the state’s political boundaries, rejecting — for the third time in barely two months — new maps of state legislative districts that heavily favor the Republican Party.

The decision appears likely to force the state to postpone its primary elections, scheduled to take place on May 3, until new maps of both state legislative seats and districts for the United States House of Representatives pass constitutional muster.

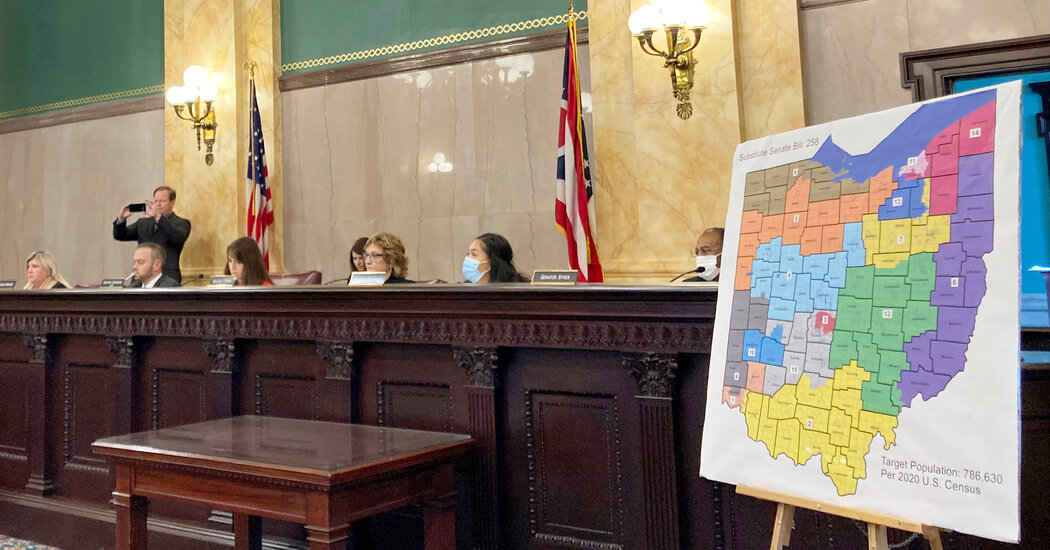

The court’s ruling late Wednesday was a blunt rebuff of the Ohio Redistricting Commission, a Republican-dominated body that voters established in 2015 explicitly to make political maps fairer, but that now stands accused of trying to fatten already lopsided G.O.P. majorities in the state’s legislature and the U.S. House.

Ohio has become the heart of a nationwide battle over political boundaries that has assumed life-or-death proportions for both Republicans and Democrats, one in which courts like Ohio’s have played an increasingly crucial role.

With redistricting complete in all but five states, Democrats have erased much of a huge partisan advantage that Republicans had amassed on the House of Representatives map by dominating the last round of redistricting in 2011. Democrats have also rolled back some of the Republican gerrymanders that have allowed the party to dominate state legislatures.

The minority justices in the 4-to-3 ruling in Ohio, all Republicans, said in a bitter dissent that the decision “decrees electoral chaos” by upending election plans and fomenting a constitutional crisis. But the four majority justices, led by Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor, a Republican, said it was the Redistricting Commission that was creating chaos by repeatedly drawing maps that violated the State Constitution’s mandate for political fairness.

Constitutional scholars and Ohio political experts have said the Redistricting Commission had been betting that the high court would be forced to approve its maps so that it would not shoulder blame for disrupting statewide elections. The court has already complained of foot-dragging by the commission, threatening last month to hold its members in contempt for failing to produce a new state legislative map on time.

“There’s this attitude that ‘if we can’t get our way with the court, we’re going to try to run out the clock on them,’” Paul De Marco, a Cincinnati lawyer who specializes in appeals cases, said of the Redistricting Commission, which is made up of five Republicans, including Gov. Mike DeWine, and two Democrats.

With the ruling this week, the court effectively called the commission’s bluff.

“This court is not a rubber stamp,” Justice Jennifer Brunner, a Democrat, wrote in a concurring opinion. “By interpreting and enforcing the requirements of the Ohio Constitution, we do not create chaos or a constitutional crisis — we work to promote the trust of Ohio’s voters in the redistricting of Ohio’s legislative districts.”

The stalemate is playing out in a state whose 15 House seats — the seventh-largest congressional delegation in the nation — represent the second-largest trove of congressional districts whose boundaries remain to be drawn for this year’s midterm elections. (Florida, with 28 House seats, is the largest.) The delegation’s partisan makeup could determine control of an almost evenly divided House of Representatives.

What to Know About Redistricting

The Ohio Supreme Court is also in a standoff with the Redistricting Commission over the state’s congressional map, having already rejected one version in January as too partisan. It is considering a lawsuit seeking to invalidate the commission’s newly redrawn map of Ohio congressional districts, which would create solidly Republican seats in 10 of the 15 districts. The map would leave Democrats with three safe seats and two competitive seats where the party would hold slight edges.

The fight over the maps could well move to federal court, where Republicans have asked that a three-judge panel be created to consider instituting the Redistricting Commission’s rejected maps so that elections can proceed. Chief Judge Algenon L. Marbley of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio declined to act on Monday, noting that the State Supreme Court was considering the maps.

But Judge Marbley, who was appointed by President Bill Clinton, indicated that he would step in if there were “serious doubts that state processes will produce a state map in time for the primary election.”

In North Carolina, Pennsylvania and some other states, state supreme courts have played decisive roles in redistricting this year, casting aside gerrymanders in favor of fairer maps often drawn by nonpartisan experts. The Ohio court is at an impasse because the State Constitution allows the court to reject maps it deems unconstitutional, but gives it no clear authority to make maps more fair, much less to adopt ones that the commission did not draw.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

Ohioans thought they had abolished hyperpartisan political maps for good seven years ago, when they resoundingly approved a constitutional amendment that took mapmaking authority away from politicians in the legislature and gave it to the new commission. That referendum ended a long struggle between voting rights advocates and political leaders of both parties, who had resisted any change in the mapmaking process.

The two sides struck a compromise that gave politicians control of the Redistricting Commission, filling its seven seats with elected officials and their appointees, generally favoring the party in power. In return, voting rights groups were granted one of their wishes: a constitutional mandate that the commission draw maps that “correspond closely to the statewide preferences of the voters of Ohio,” based on the previous decade’s elections.

Seven in 10 voters approved the 2015 amendment. Three years later, another amendment effectively extended the deal to congressional maps.

“This issue is proof that when you work together in a bipartisan manner, you can accomplish great things,” Matt Huffman, a Republican state representative from Lima who campaigned for the 2015 amendment, said after it passed.

Today Mr. Huffman is the president of the State Senate and sits on the Redistricting Commission. But he now says that the constitutional requirement that maps reflect voters’ preferences was only “aspirational” — a view the Supreme Court rejected in January.

Jen Miller, the executive director of the League of Women Voters of Ohio, said that “we mobilized more than 12,000 Ohioans to advocate for fair maps through emails, phone calls and even submitting their own maps.”

She added: “What’s disappointing, and shocking for most of us, is that it’s business as usual. Nothing has changed.”

How U.S. Redistricting Works

What is redistricting? It’s the redrawing of the boundaries of congressional and state legislative districts. It happens every 10 years, after the census, to reflect changes in population.

The League and Common Cause, another advocacy group that pushes for voting rights, were the driving forces behind the 2015 and 2018 amendment votes.

Neither Mr. Huffman nor his spokesperson responded to requests for interviews. Nor did the Republican speaker of the State House, Representative Robert R. Cupp, who also sits on the commission.

The two legislators have controlled mapmaking by the Redistricting Commission, whose handiwork has leaned heavily toward preserving gerrymandered G.O.P. majorities in both the State House and Senate.

The constitutional amendment said maps should aim to reflect voters’ preferences in the 16 statewide elections over the last decade, which split roughly 54 percent to 46 percent in favor of Republican candidates. But the first state legislative map sent to the court awarded the G.O.P. as many as seven in 10 seats in the House and Senate, even larger than the party’s existing supermajorities.

Republicans have defended their maps with displays of statistical sleight of hand. The true measure of voters’ preferences, they first said, was not the 54-to-46-percent division of votes, but the share of statewide elections that Republicans had won — 13 of 16, or 81 percent.

After the Supreme Court rejected that reasoning, Republicans submitted new legislative maps that roughly tracked party preferences, but placed Democrats in districts that were effectively tossups. None of the Republican seats in the maps were in similar peril.

The court rejected that map, too, saying that even if the tossup seats were evenly split between the two parties, Republicans would emerge more dominant in the legislature than they already were.

The third map of state legislature seats that the court struck down on Wednesday was even more partisan than the second one, the court said. It nominally gave Democrats the edge in 46 of the state’s 99 House districts, up from the 34 the party currently holds. But 19 of those seats are actually tossups in which Democrats have won less than 52 percent of the vote on average, while only two Republican districts have an average G.O.P. edge of less than 55 percent of the vote.

The situation is similar in the State Senate, where seven Democratic districts would be tossups, while all Republican seats would be safe.

“The result,” the justices wrote, “is that the 54 percent seat share for Republicans is a floor, while the 46 percent share for Democrats is a ceiling.”

The 2015 amendment laid out a tortuous set of directions for handling partisan disputes over maps, including the adoption of interim maps, the ones now being challenged in court. If all else fails, a majority of the Redistricting Commission can approve a map that is good for only four years instead of 10 — punishment, everyone thought, for not playing by the rules.

Republicans, however, have a plan for that eventuality. Chief Justice O’Connor must retire this year, and the legislature has ordered that future ballots for the Supreme Court — whose justices are elected by Ohio voters — list the party affiliation of candidates, presumably giving the G.O.P. an edge in a state that has trended conservative. Four years from now, the court may look at skewed maps with a gentler eye.

Justice O’Connor has her own thoughts on a solution. “The current Ohio Redistricting Commission — comprised of statewide elected officials and partisan legislators — is seemingly unwilling to put aside partisan concerns as directed by the people’s vote,” she wrote in an opinion rejecting the first legislative maps. Given that, she added, “Ohioans may opt to pursue further constitutional amendment to replace the current one with a truly independent, nonpartisan commission.”