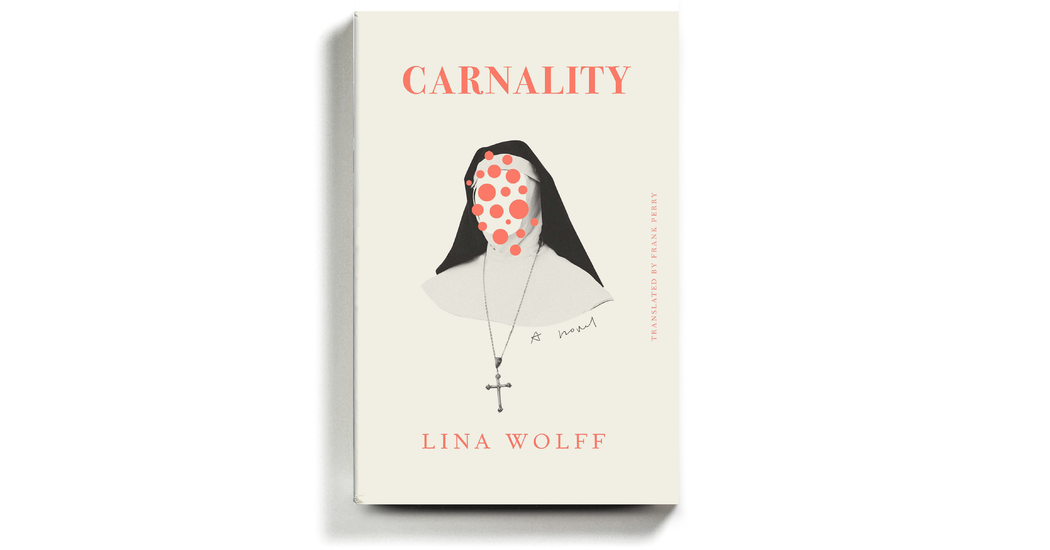

CARNALITY

By Lina Wolff

Translated by Frank Perry

357 pages. Other Press. $17.99.

“Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life.

Premise established, we are safely buckled in for the ride, which rumbles along a scenic track for roughly five minutes before a crazed carnival operator assumes the controls and we take off at warp speed through loops, inversions and spins. The third-person narration turns into a monologue from a secondary character, which morphs into a memoir in the form of letters from a third character. When an author tries and fails to pull off this level of formal sorcery, it feels like being pantsed on the playground. (Startling. Unfair.) When an author succeeds, as Wolff does, it replicates the optimal sensation of intoxication: Suddenly anything can happen! And you want it that way!

After landing in Madrid, the woman — who is given the unusual name of Bennedith — heads to a bar and meets a man called Mercuro Cano. Mercuro displays a parade’s worth of flags, all of them red. He is sweaty and shaky, with a darting glance. He buttonholes Bennedith and tells her a story about the time he was wronged by an evil nun with a maimed hand. He begs Bennedith to hide him “for a few days.” When she tries to leave, twice, he grabs her arm and begs.

Many people would end it there, writing off Mercuro as paranoid and creepy, but Bennedith texts him the next day and invites him to stay at her apartment. Bennedith, it turns out, is a woman who follows the improvisational comedy rule of “Yes, and…” Like the novel in which she appears, her experiences have predictable beginnings, mind-bending middles and astonishing ends. Why exchange small talk with a random guy when you can welcome the random guy into your home, download his entire appalling life story, go on vacation with him, fall in love and commit a felony? While you’re at it, why not dare another tourist to eat a live octopus? Or walk naked across a public beach? Or steal a boat?

Perhaps Bennedith’s attraction to Mercuro is rooted in a shared existential malady. They are each in a state of mummification and yearn for a transformative event — a miracle or a cataclysm, either works — to get the life juices flowing again. Precisely halfway through the novel, such an event takes place.

Until then, Bennedith exhibits extremes of both passivity and action. Often she is borne along in jellyfish mode. Sometimes, without warning, she strikes. The concept of “boundaries” is as foreign to her as an iPad would have been to Francisco Goya or General Franco, the only two historical Spaniards whose names appear in the book. It’s impossible to read “Carnality” without fantasizing about the twists your own life might take if you adopted her methodology.

The book’s title comes from a game show of the same name, where volunteers reveal humiliating secrets on a live broadcast that can be seen only on the dark web. This is where the evil nun comes in. Lucia, at 93 years old, is the show’s inventor. She takes breaks from convent life to curate mediated displays of masochistic self-disclosure that range from adultery to phone addiction. Mercuro was among the contestants.

Wolff is Swedish, and has published two novels and a book of short stories, all to acclaim. She has translated works by César Aira, Roberto Bolaño, Gabriel García Márquez and others into Swedish. “Carnality” was originally published in 2019, and has been translated into English by Frank Perry. I don’t read Swedish, so I’m unsure how to apportion credit for beautiful sentences, but they abound: Snide comments are “tiny puffs of marsh gas.” Misery feels like one’s “insides are a large wet ball of yarn that is refusing to dry out even in the sunshine.”

Wolff has long been interested in male aggression and female sexuality, and in the diminishment of power that occurs when a man loses his ability to exert violence or a woman ages out of her capacity to seduce. Her fiction is filled with references to other texts. A character in “The Polyglot Lovers” finds a stash of Michel Houellebecq novels hidden at the back of a man’s bookcase. In her debut novel, a dog at a brothel is named Bret Easton Ellis. In “Carnality,” Nietzsche is rampant.

But this novel is mostly concerned with the social category of the stranger. It won’t ruin the plot to say that Bennedith and Mercuro become entwined as deeply as two people can: sexually, spiritually, criminally, and all without performing the initial cyberstalking that is now a condition of human interaction. By scorning this routine digital probing, they attenuate their safety and intensify their exhilaration in roughly equal measure.

In a sly manner, they are strangers to the reader as well. We learn almost nothing about their childhoods. Wolff includes few signifiers of class or taste. No brand names. No discussion of jobs, education or real estate. We know little of what Bennedith consumes, whether it be food, literature, entertainment or clothing.

Withholding these clues — denying the modern reader’s lazy appetite for shorthand — is a moral intervention: Wolff wants us to know these people through their actions, not their diplomas or haircuts. It’s also a clever way of forcing us to have an imagination.