(Bloomberg) — With the future of the US telehealth industry at stake, Bart Stupak, a former congressman and current lobbyist, has spent the past year trying to undo legislation he helped pass more than a decade ago.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Stupak is asking federal policymakers to let online clinicians keep prescribing controlled substances — even though federal investigators are looking at that practice and have interviewed former employees at two telehealth startups, according to people familiar with the conversations. One of those companies, Done Global Inc., specializes in treating attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder with prescription stimulants and has paid Stupak’s firm $150,000 for the lobbying effort.

Fourteen years ago, Stupak sponsored legislation that effectively banned online-only prescriptions for controlled substances — a bill that came after Ryan Haight, a California teenager, died from overdosing on opioids he obtained from a website. That prohibition remained in effect until 2020, when the global pandemic’s lockdown pushed patients toward telehealth providers. To help ensure access to care, the US Drug Enforcement Administration temporarily relaxed the ban.

Now, Done — which markets its ability to treat ADHD after a “30-minute appointment” and touts “worry-free refills” — has joined other telehealth providers in seeking to end the prohibition permanently.

Stupak, who represented northern Michigan as a Democrat in Congress, says the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act is overdue for revision. He declined to comment about federal agents interviewing Done employees. The company didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“I find it very frustrating that the Ryan Haight Act was written in 2008 and the DEA has still yet to take action and develop guidelines for how to treat patients online,” Stupak said in an interview, noting that many people have become reliant on telehealth since the pandemic hit. “How do you put the genie back in the bottle after two years?” He has asked the DEA to craft rules exempting prescribers and patients from in-person appointment requirements. Without that sort of intervention, the law could revert to its original form when the pandemic’s public health emergency expires, likely in early next year.

A spokesperson for the DEA declined to comment, pointing to a March 2022 press release — one of the agency’s few public statements on the issue — that says it’s working toward rules that would permanently allow online prescriptions, but specifies only one type of care: “medication-assisted treatment” of patients with substance-use disorders. MAT uses controlled medications to ease patients’ withdrawal symptoms and otherwise aid in clinical responses to such disorders. The agency hasn’t taken a public position on other drug therapies, such as for ADHD.

Medical experts say the act could use some refinements, and many favor an MAT allowance. But questions surrounding the way some telehealth startups have used their online prescribing privileges show that the issue remains fraught with safety concerns. Jason Doctor, a professor at the University of Southern California who studies telehealth and behavioral science, said amendments to the 2008 act could prove helpful, but he remains skeptical of relaxing the ban fully.

“Maybe I am too cynical. I’m not convinced that they’re all good actors out there doing telehealth right now,” he said, without identifying any particular company.

DEA agents have interviewed employees of Done about controlled substance prescriptions, according to people familiar with the matter. The company didn’t reply to multiple requests for comment. Another telehealth company, Cerebral Inc., faces a federal government investigation into alleged violations of the Controlled Substances Act. A Cerebral spokesperson said the company is cooperating with the probe.

Stupak said Done would welcome additional safeguards, like third-party verification to check patients’ identities and a requirement that clinicians review patients’ full medical histories before prescribing controlled substances. In an October press release, Done said it already employs another safeguard, noting that “all patients must complete screenings for current controlled substance use.”

Such guardrails were at the core of the protections envisioned by policymakers when the law was being crafted. Speaking to a Senate subcommittee in 2004, Ryan Haight’s mother, Francine, said her hope was “that with tighter restrictions on the internet and more public awareness, we can save lives.”

Ryan, at age 17, had ordered hydrocodone and Valium online. The prescription was filled by NationPharmacy.com, a digital pharmacy, and the script was written by a doctor who had never met Ryan. His parents turned over his computer to the DEA, and doctors and pharmacists involved were charged with conspiracy to dispense controlled substances and sentenced to decades in federal prison.

Since the act’s passage in June 2008, members of Congress have sought to create a “special registration” that would allow clinicians who submit to vetting by the DEA to prescribe controlled substances in telehealth settings. In 2019, the agency began working on a rule to permit such a registry. The standards the prescribers would have to meet under the proposed rule haven’t been released, and the DEA declined to comment on them. The Office of Management and Budget, which would sign off on the rule, said it was still under review and declined to comment.

Medication-assisted treatments for patients with substance-use disorders may eventually become the backbone of the DEA’s special registration. Several telehealth startups — including Cerebral, Bicycle Health and Ophelia Health — provide MAT, which typically involves the use of medications such as Suboxone to help reduce the physical dependence to opioids like fentanyl.

Given the widespread need for such treatment, Doctor agrees the law needs revision. “It either needs to be rewritten or amended in a way that addresses that we are in this second stage of the opioid crisis where we have this burgeoning fentanyl problem,” he said.

While the medications used are controlled substances themselves, medical experts say their potential for abuse is lower. Regardless, in keeping with the federal government’s broad classifications of controlled substances, the Haight Act focused on all such drugs, applying the same ban to Suboxone as to stimulants like Adderall and anxiety treatments like Xanax. Likewise, the DEA’s 2020 suspension of that ban lifted the limitation on all such medications. Some experts say regulators should distinguish among particular drugs going forward.

“It’s ironic that the life-saving medications that treat opioid use disorder face the same set of rules as medications that lead to addiction,” said Haiden Huskamp, a professor of healthcare policy at Harvard Medical School. “The set of controlled substances are very diverse. You might imagine a world where the future regulatory processes treat them differently.”

Some interested parties want them treated the same. In a March 2022 letter to the DEA, the American Telemedicine Association cited the importance of addiction treatment but advocated broadly for officials to “remove the in-person requirement permanently.” The group said in a statement that it “believes all clinically appropriate controlled substances, now able to be prescribed remotely without an in-person requirement, should be allowed post-pandemic.”

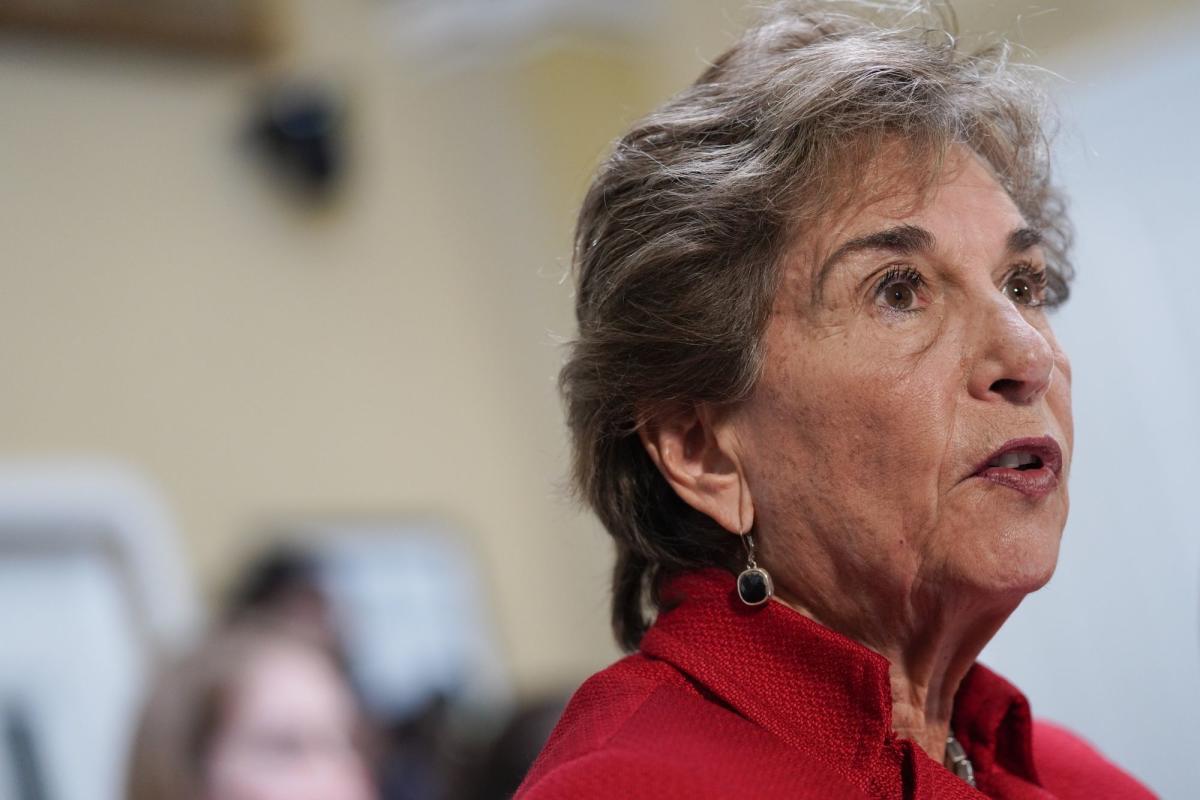

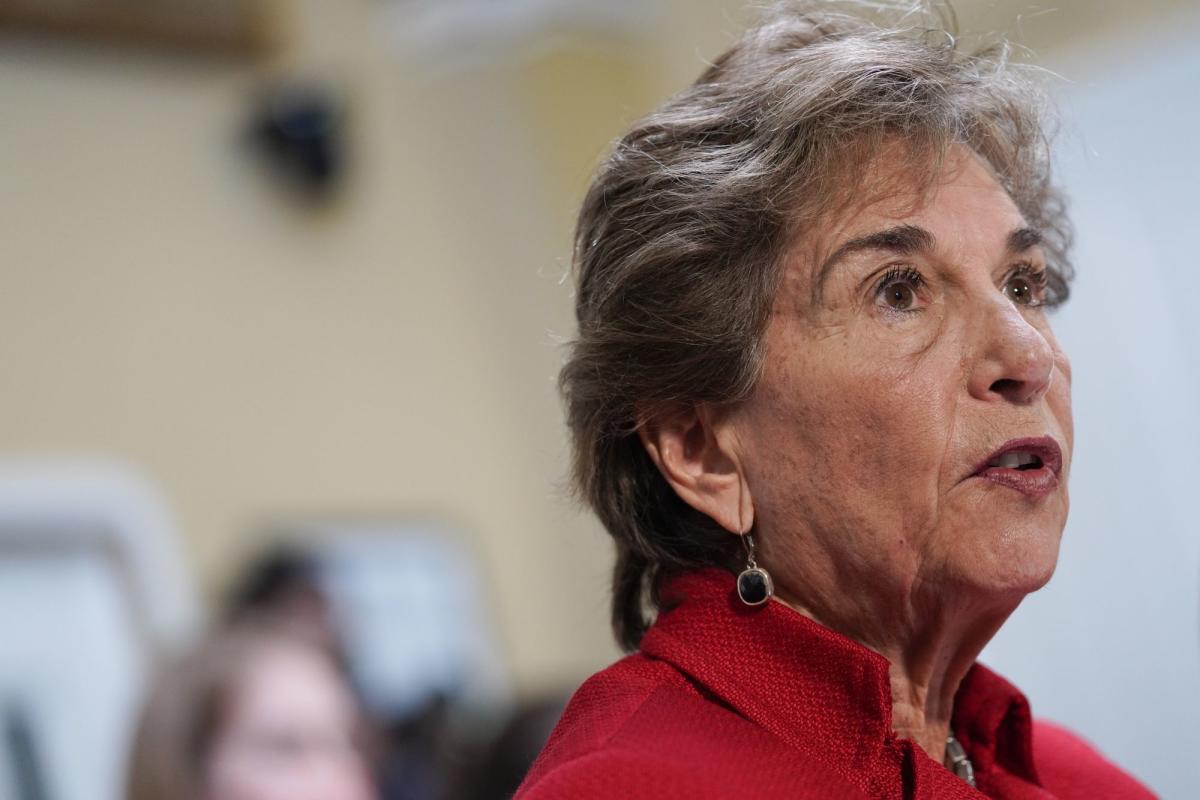

Some federal lawmakers say they simply want action. Representative Jan Schakowsky, a Democrat from Illinois who met with lobbyist Stupak earlier this year, expressed frustration that the special registration still hasn’t been created. She has no stance on which types of drugs should be dispensed via telehealth, Schakowsky’s office said, but she wants federal officials to move forward on the rule, no matter what it dictates.

“A proposed rule, which was mandated by Congress and has been pending at the OMB since last March, must be released,” she said in a statement. “We know that health providers can effectively and efficiently care for their patients virtually.”

There are plenty of arguments for taking a broad approach that would include mental healthcare, which remains difficult to obtain in the US, with long waitlists and high co-pays for psychiatric care. Getting traditional ADHD treatment can take months; many of the new telehealth businesses promised to eliminate the delay.

In the early days of the pandemic, some of the startups took advantage of the temporary change in the law with advertising that offered access to clinicians who could prescribe stimulants, like Adderall. By mid-2022, then-industry leader Cerebral said it would stop prescribing most controlled substances, including stimulants. A spokesperson for the company said it has not participated in any lobbying to seek a lasting relaxation of the law but added: “The removal of the in-person requirement is in the best interest of the patient and increases access to care.”

If the Haight Act is allowed to revert to its original form — reinstating broad limits on telehealth prescriptions — some policymakers predict negative effects on patients.

“Reinstating regulations put in place by the Ryan Haight Act without taking into account the shift in how treatment has been delivered for the last two and a half years will cause serious disruptions to care,” Senator Mark Warner, a Virginia Democrat, said in a statement. In August, he wrote a letter to the DEA that sought to clarify how the law may change. Warner’s office said he defers to medical experts to determine which medications should be allowed to be prescribed remotely. Warner said in a statement that he’s pushing the DEA for a plan on how to handle patient care after the health emergency expires.

Telehealth would not cease to exist if the act reverts to its original form. (Some teleproviders also have in-person offices that could see patients for their initial appointments.) But with startups leaning on a model that sometimes pairs patients with far-flung nurse practitioners who practice online only, returning the rules to pre-Covid restrictions would significantly change their business model.

“I do think that the industry itself will continue,” said Mei Kwong, executive director of the Center for Connected Health Policy, a nonprofit that advocates for telehealth. “But it is going to be more difficult for certain patients to access services.”

–With assistance from Caleb Melby and Jackie Davalos.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.