The idea that forever changed Super Bowl halftimes struck Jay Coleman while watching Snoopy conduct a marching band and Charlie Brown twirl a baton.

Inside the Louisiana Superdome, bored out of his mind, Coleman refused to accept that an ode to New Orleans and the Peanuts comic strip was the best America’s biggest sporting spectacle could do for halftime entertainment.

The January 1990 show’s lack of sizzle and star power was hardly unusual in those days. Most Super Bowl halftimes of that era were a chance to make a beer run or load up on snacks. An Elvis impersonator known as Elvis Presto was the previous year’s headliner. The years before that featured college marching bands, aging entertainers and the cult-like singing ensemble group, Up With People.

“Who wants to watch that? Who wants to watch marching bands?” Coleman’s wife, Susan Coleman-Feilich, recalls him telling her when he returned home.

Through his boredom and bewilderment, Coleman sensed opportunity. He realized that a reimagined halftime show could broaden the Super Bowl’s already unparalleled reach by attracting more viewers who didn’t normally watch football.

Coleman was the founder of a pioneering New York music marketing firm that negotiated some of the first major partnerships between corporations and rock stars. He saw firsthand the impact the right A-list pop star could make, having brought together Pepsi and Michael Jackson at a time when the cola giant was trying to paint itself as a younger, fresher alternative to Coke.

In early 1990, Coleman approached PepsiCo CEO Roger Enrico to gauge his interest in a Frito-Lay-sponsored Super Bowl halftime show built around MC Hammer or another headline-grabbing music act. Enrico jumped on board, but the NFL did not. The league saw no need to overhaul its Super Bowl halftime model or to drastically increase the cost of staging the show.

“At the time, they were getting this free ride on the advertising,” said Jerry Noonan, then-Frito-Lay’s vice president of marketing. “Everyone walked away from their TVs and didn’t pay attention during halftime, yet they were still getting the same ad rates they did during the game.”

Frustrated after the failed meeting with the NFL, Coleman did not give up. He instead came up with a more brazen idea, one now universally credited with jolting the NFL out of its complacency and paving the way for the modern, star-driven Super Bowl halftime, like the Dr. Dre-headlined show planned for Super Bowl LVI on Sunday.

If the NFL wanted Super Bowl halftimes to be about college marching bands and cheesy costumed dancers, so be it. Coleman would put together something better and organize an ambush.

Upstart Fox was game to change Super Bowl halftime shows

To pull off a stunt as audacious as counterprogramming the Super Bowl, Coleman needed a lot to go right. Among his must-haves were content compelling enough to entice viewers to change channels at halftime, a network willing to risk alienating the powerful NFL, and a sponsor comfortable financing the project and promoting it.

Coleman’s most important ally was Enrico, the risk-taking PepsiCo CEO whose bold advertising campaigns during the so-called Cola Wars nearly overtook Coca-Cola. Enrico gave Coleman’s idea life when he threw Frito-Lay’s support behind it, gambling that the alternative halftime show they produced could serve as a platform to launch a new bite-sized Doritos product.

“Roger had the courage that few CEOs had,” Noonan said. “He took a lot of risks as a marketer and this was a big one.”

The quest to find a network for the project wasn’t quite so easy. CBS wasn’t an option since it had the broadcast rights to Super Bowl XXVI. NBC and ABC also had contracts with the NFL at the time. Wary of offending the league, they treated the notion of counterprogramming the Super Bowl like it was radioactive.

That left Fox, who in 1991 was still an upstart network seeking to loosen the stranglehold the Big Three had on American television. Fox didn’t yet have the reach that it has today, but it had the rules-be-damned, rebellious spirit to embrace an attempt to vulture viewers from the Super Bowl, which would feature Washington vs. Buffalo at the Metrodome in Minneapolis.

“The idea was just so perfectly representative of everything Fox stood for back then,” said Sandy Grushow, then the executive vice president of Fox Entertainment. “We kind of formed as an alternative to the Big Three. We were contrarian. We used to say that we liked to zig when everyone else was zagging. We were guerilla-like in our approach because we had to be. We were so much smaller and less powerful than the other guys that we had to run in, throw our punch and run the hell out before they knew what hit them.”

To Coleman, there was one Fox show whose daring humor was the ideal counterprogramming for the NFL’s bland halftimes. Coleman and his wife hardly ever missed an episode of “In Living Color,” the often-funny, always-edgy sketch comedy show that launched the careers of the Wayans brothers, Jim Carrey and David Alan Grier, among others.

Around the same time that Enrico brought the alternative halftime show idea to Fox, Coleman approached “In Living Color” creator Keenen Ivory Wayans about the concept. Wayans and co-creator and producer Tamara Rawitt agreed the Super Bowl halftime was ripe for a takeover, and recognized that the potential publicity could be a springboard for “In Living Color.”

“It was a novel idea, but at the same time it was also a big duh,” Rawitt said. “It was like, ‘Why didn’t anyone think of this sooner?’”

After Fox and Frito-Lay came to an agreement on a live episode of “In Living Color” spanning the entirety of halftime of Super Bowl XXVI in January 1992, Fox’s marketing department began dreaming up clever ways to advertise the show. Grushow’s favorite 30-second spot poked fun at previous Super Bowl halftime shows with stock footage of a “really horrible high school marching band that actually tripped and fell on top of one another.”

The words accompanying that video clip drove home the message.

Recalled Grushow: “It was along the lines of, ‘Why watch that at halftime when you can watch ‘In Living Color?””

‘In Living Color’ first pushed Super Bowl halftime boundaries

For all of Fox’s advertising bluster, many of the network’s executives struggled to hide their anxiety about the live broadcast as the Super Bowl approached. They wanted an edgy show that would generate conversation, yet they worried the notoriously unpredictable “In Living Color” cast might get them fined or sued.

“They were terrified because we were the naughty kids,” Rawitt said.

In Fox’s defense, there was reason to be concerned. Fights with network censors over risque material were common on the “In Living Color” set. Writers even resorted to tricking the standards department by inserting egregious decoy jokes and sketches into the script early in the week so that their favorite material appeared tame by comparison.

“By the time Friday rolled around, we seemed like we were being reasonable,” former “In Living Color” writer and producer Les Firestein said. “We’d say that we changed the joke five different times when really the joke we were putting in was the one we wanted in the first place.”

Fox ultimately took some precautions with the Super Bowl episode. “The Homeboyz Shopping Network” sketch, set inside a Super Bowl locker room, was taped in advance, as was Fire Marshall Bill’s visit to a sports bar. The rest of the live show aired on a brief delay, giving Fox’s vice president of broadcast standards, Don Bay, time to bleep out any off-the-cuff jokes he deemed unacceptable.

While Rawitt recalls writers tweaking sketches during the first half of the Super Bowl and Bay’s hand “guerilla-glued” to the button as halftime grew near, none of the behind-the-scenes stress manifested on camera. The show opened with a live studio shot of what looked like a genuine Super Bowl party. The cast mingled with guests, including Pauly Shore, Phil Buckman and Blair Underwood.

“I know what you guys are thinking,” cast member Kelly Coffield told viewers. “You’re thinking, ‘Are these bozos going to make us miss any part of the second half?’”

“That’s where this comes in,” Carrey interjected, pointing to an on-screen clock counting down to the start of the third quarter so that the TV audience didn’t have to “miss any of the senseless brutality.”

Channel surfers who flipped between the halftime shows must have felt disoriented. Over on CBS, ice skaters Dorothy Hamill and Brian Boitano welcomed viewers to “Winter Magic,” which featured dancing snowflakes, inflatable snowmen, the 1980 U.S. men’s hockey team and, oddly enough, Gloria Estefan. CBS billed it as a “kaleidoscopic salute to all the fun and fantasy” associated with Minnesota winters. In reality, it also doubled as a poorly disguised advertisement for the network’s Winter Olympics coverage the following month.

“In Living Color” certainly produced a more compelling halftime show, but, as Grushow admitted, “it was a bit of a white-knuckle ride.” That was never more true than during a “Men on Football” sketch when Damon Wayans’ ad-libbing left advertisers grumbling and Fox wondering if its censors were too lenient.

In the sketch, Wayans and David Alan Grier portrayed flamboyantly gay cultural critics Blaine Edwards and Antoine Merriweather. They had already unleashed a barrage of tight end quips and football-themed double entendres when Wayans decided to test how much leeway he had.

Wayans first snuck in a cringeworthy joke about a Hollywood leading man’s sexuality. Later in the sketch, Wayans also thoughtlessly quipped that a decorated Olympian couldn’t run from speculation that he was gay. By the time the show went off the air a few minutes later, the phones on set were already ringing.

Whatever residual anger there was at Fox or Frito-Lay largely faded the next day when ratings came out. “In Living Color” captured 20 to 25 million curious viewers, a massive number for any show up against the Super Bowl. CBS’ Super Bowl rating declined sharply during halftime and never fully recovered thereafter.

Fox executives “were jumping with joy” over the ratings, Grushow recalled.

Meanwhile, at the NFL’s offices, the mood wasn’t so jubilant.

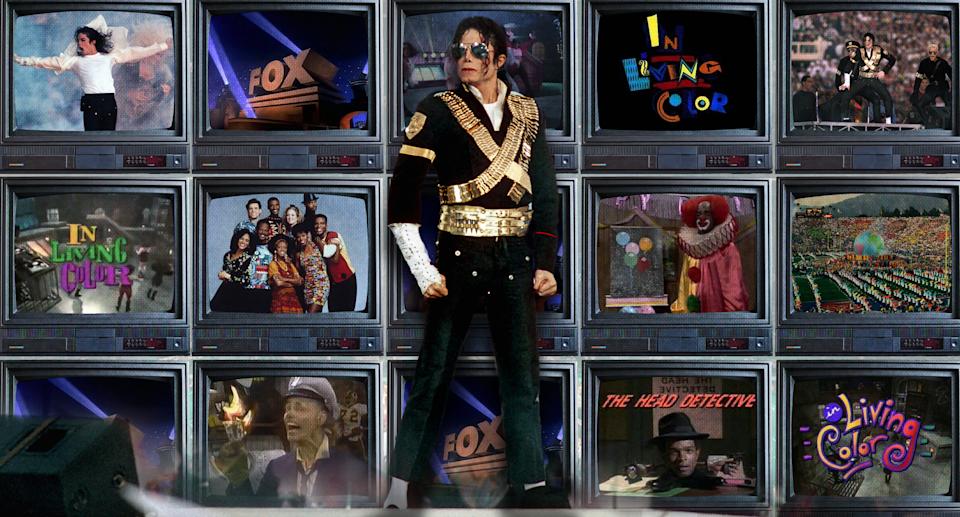

NFL’s response? Michael Jackson, who was ‘as big as we could go’

Jim Steeg, then the NFL’s vice president for special events, said the league was aware of Fox’s halftime counterprogramming before it aired, but “nobody paid that much attention to it.” That changed in an instant when it became clear how many viewers “In Living Color” had siphoned away.

At long last, the NFL admitted that it couldn’t keep clinging to its outdated halftime model or pretending that star power didn’t matter. The NFL needed a performer, someone who could engage with an audience at home and in a stadium, someone who could drive home the message that the Super Bowl could not be counterprogrammed.

It needed Michael Jackson.

“We wanted to go as big as we could go,” Steeg said, “and at that time he was as big as it got.”

In 1992, the pursuit of the King of Pop took Steeg and then-Radio City Music Hall CEO Arlen Kantarian to Jackson’s manager’s office in Los Angeles. There, they learned that Jackson wasn’t too familiar with how big the Super Bowl was. At one point Jackson said he didn’t like the name and asked, “Why don’t we rename it the Thriller Bowl?”

Chuckling at the memory, Kantarian said, “I’m going to assume it was a joking request, but it didn’t come off like that.”

What finally sold Jackson on performing at the Super Bowl was the discovery that the game would be broadcast to 120 countries, including many developing nations. He became intrigued that people who would never attend one of his concerts could watch him perform live and hear his message of hope.

The rest of the meeting evolved into a negotiation over how the show would go. Kantarian and Steeg agreed to most of Jackson’s conditions until he said he wanted to do his wincingly sweet new ballad, “Heal the World,” and other songs from his new album “Dangerous” for the entirety of the 12-minute concert.

“We had to gently encourage him to make sure he grabbed the audience with some of his No. 1 hits,” Kantarian recalled.

In the end, Jackson agreed to do a medley of four of his most beloved songs before closing with an extravagant version of “Heal the World.” The NFL sweetened the deal by offering a 30-second ad spot for Jackson’s Heal the World Foundation and $100,000 in donations.

Jackson had been opening shows on his tour by launching himself onto the stage, then holding a pose until audience anticipation reached a crescendo. He pulled that same stunt to begin his Super Bowl show, remaining motionless in his blue-and-gold military jacket and shades with the cameras trained on him and much of the Rose Bowl crowd growing restless.

Thirty seconds went by … then 40 … then 50. Only after 72 seconds — the 1993 equivalent of more than $2 million in Super Bowl advertising time — did Jackson finally whip his head from right to left, then give the signal to start the music.

“We were a little surprised by that,” Kantarian said. “We were thinking, ‘What else are we going to see that we did not rehearse?”

Super Bowl halftimes haven’t been the same since Michael Jackson

The rest of the show, it turns out, could not have gone better. Even “Heal the World” was a hit, aided by an elaborate card stunt in which the entire crowd revealed massive images of cartoon children holding hands.

One year after Super Bowl ratings plunged during halftime, this time it was the exact opposite. More people watched Jackson’s performance than the Dallas Cowboys’ rout of the Buffalo Bills. The final minutes of Jackson’s show were the most viewed in television history at the time.

“He absolutely killed it,” Kantarian said. “When people saw the success of that show and how it helped to promote the album ‘Dangerous,’ we had countless other big-time performers say yes.”

What Jackson’s performance proved to the NFL is the same thing Jay Coleman told the league three years earlier. A star-driven halftime show can broaden the Super Bowl’s audience by attracting new viewers who wouldn’t normally watch football.

In the nearly three decades since Michael Jackson, the Super Bowl has become a showcase for some of the world’s most beloved musical acts. Diana Ross, U2, Justin Timberlake, Prince and Paul McCartney have each headlined the Super Bowl halftime show, as have Tom Petty, Bruce Springsteen, Beyonce, Lady Gaga and Madonna.

“Now I think a lot of the artists look at it like a bucket list type thing,” Steeg said.

While Jackson displayed courage performing live in front of millions of viewers with sketchy lighting and no sound check, he alone doesn’t get all the credit for dragging Super Bowl halftimes out of the marching bands and dancing snowflakes era. It wouldn’t have happened without the risque brand of “In Living Color” comedy, without Fox’s anti-establishment ethos, or without PepsiCo’s willingness to take a marketing risk.

And it wouldn’t have happened without Coleman, the man who forever changed Super Bowl halftimes with his audacious idea to ambush one.

On Nov. 27, 2011, Coleman died after a battle with esophageal cancer, leaving behind a legacy of creativity and innovation. TV commercials advertising the Super Bowl or the halftime show often send Coleman-Feilich back to the early 1990s

“There isn’t a day that goes by this time of year when I don’t think about it,” Coleman-Felich said. “Halftime has never been the same since.”