Sarah Bolton maneuvers in the air for a living, using silks and hammocks to defy gravity at heights of up to 25 feet. The sensation of being in the air, she said, is often one of empowerment, an extension of childhood fantasies becoming adult realities.

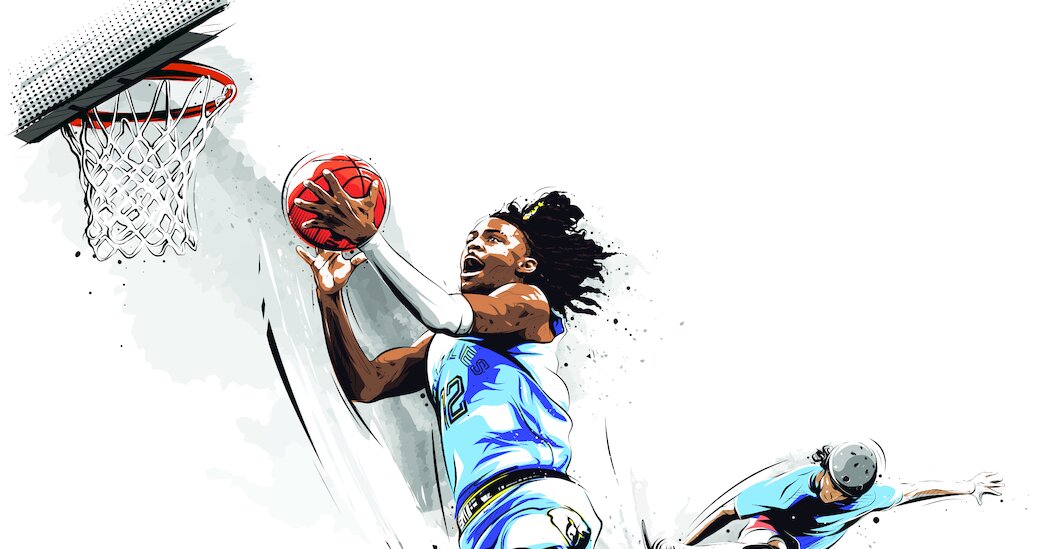

Bolton runs the aerial arts school High Expectations in Memphis, where Ja Morant, too, is a high-flyer, as the All-Star point guard of the N.B.A.’s Grizzlies. Bolton said she can appreciate the similarities between her livelihood and Morant’s, especially his windmill dunk to finish an alley-oop against the Orlando Magic last season.

“To do that while he’s in the air with nothing to push up against, that’s incredible,” Bolton said.

One aerial artist can certainly recognize another.

Morant’s Grizzlies, set to play the Minnesota Timberwolves in the first round of the playoffs, were one of the most satisfying surprises this season. Memphis finished 56-26, second in the Western Conference, with an exciting young core who compete at a frenetic pace. They are a far cry from the popular grit-and-grind Grizzlies of the 2010s who pounded the ball in to post mainstays like Zach Randolph and Marc Gasol.

Morant is the lofty, dynamic centerpiece to Memphis’s makeover, a guard who skies in the air and executes in a manner arguably unvisited since the ascendant takeoffs of Vince Carter and Michael Jordan.

Not many people in the world — N.B.A. players included — know what it’s like to elevate and seemingly levitate quite like Morant. He recorded a standing vertical leap of 44 inches before the Grizzlies drafted him No. 2 overall, behind New Orleans’ selection of Zion Williamson, in 2019.

“Think it’s just pure skill,” Morant said. “I don’t know too much that I can say about it. It’s just a natural thing for me.”

But some in Memphis and West Tennessee, those like Bolton who often operate in the air, recognize and applaud Morant’s vertical capabilities.

“I enjoy the looks on his face when he has those moments,” Bolton said. “He does these things that you think is physically impossible and it’s just this pure joy.”

The 6-foot-3 Morant is a few inches shorter than his vaulting predecessors Carter and Jordan, which makes his gravity-defying exploits all the more impressive.

He is an aerial dynamo playing in an era when most players his height are stretching the game horizontally by expanding their shooting range. He does that, too, but he lives in the air.

There was his dunk all over Jakob Poeltl, the San Antonio Spurs’ 7-foot-1 center, in February, and his soaring left-handed alley-oop finish against the Boston Celtics in March. In January, Morant used both of his hands (and banged his brow against the backboard) against the Los Angeles Lakers to block Avery Bradley’s attempt. “Instinctual,” Morant said of his elevation efforts.

And those are just some of his displays from this season.

“Like, how do you bump your head on the backboard,” said Aaron Shafer, a California transplant who opened Society Memphis, an indoor skating park and coffee shop. “I don’t understand it.”

Even Morant’s misses provide highlight-worthy clips because of his athleticism and the audacity of his imagination.

Morant did not start dunking regularly until near the end of his high school career in Sumter, S.C. By then, Williamson, a former A.A.U. teammate, had long ago become a national dunking sensation.

For a while, Morant had the ambition, but not the ability.

“It’s a practiced intuition,” Shafer said. “It’s something that he’s put so many hours into over his lifetime, starting as a kid. You are having the right to have that intuition, it’s not something that you just get.”

Sawyer Sides, a 14-year-old BMX rider at Tennessee’s Shelby Farms, equated Morant’s ability to anticipate plays before his leaps with competing in a motocross race.

“Say I’m in second or third,” Sides said. “I have to get where other people aren’t if I want to make a pass. You can see a window opening 10 seconds before it even starts happening. It’s like him thinking about the play as if he’s on the other side of the court already.”

SJ Smith, who is training to become an instructor at High Expectations, said Morant’s successful vertical forays begin when he steers his momentum into a strong plié and bends his knees before lifting off.

“In order to gain height, you have to set that up,” Smith said. “He is so kinesthetically intelligent and intuitive, where he’s internalized and practiced a crap ton to set himself up to be a magician up there.”

Bolton, a former dancer, entered aerial arts for the freedom that operating in the air provides.

Like a Morant dunk, aerial artistry involves a mix of control and technique through core and upper body strength and the constant interplay between activating muscles and releasing them.

“You have to really understand where your body is in space before you can layer on the momentum,” Bolton said. “Using momentum, you’re putting your body almost at the whim of this external force, but you have to learn how to control it. When I watch Ja do what he does, it’s similar. He’s so strong, but there’s also this float and this release that he finds.”

Bolton thought back to the play against Orlando last season, when Morant appeared to pause midair to control the basketball before continuing his ascent.

“He’s using the scissoring of his legs to basically pass power to himself upward,” Bolton said. “It’s like he’s using his body to create resistance in the air. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a basketball player do it to that extent.”

Alex Coker, a tandem instructor for West Tennessee Skydiving, likened Morant’s adaptability under duress to what is required of him in his job taking people thousands of feet in the air before jumping from a plane.

Coker compared each of Morant’s leaps to an emergency where he was forced to make a critical decision in milliseconds. Like Morant adjusting midair to account for an incoming defender, Coker’s job requires him to be nimble in a crisis.

“There’s pages of malfunctions of all the possibilities that could happen, and it’s very important that every 90 days we look over those emergency procedures of scenarios that we can perform like a secondhand nature,” Coker said. “If it happens you know how to instantly react.”

Of course, every jump is not the same for Morant, and neither are those by Ezra Deleon, a BMX racer and coach at Shelby Farms. His leaps can span between 20 and 30 feet, he said.

“It’s kind of a controlled chaos in a way,” Deleon said. “You know what you’re doing, but you always have a bunch of variables, like wind, other riders, how the pitch of your jump has a different weight and tosses you up in the air.”

While most aerial aficionados focused on Morant’s leaping ability, Shafer spotlighted his descent.

Sticking the landing is crucial for Morant, just like it is for Shafer in skateboarding.

Several years back, Doran, Shafer’s son who was then 10 years old, tried dunking a basketball after a 360-degree rotation in the air on his skateboard. He broke his tibia and fibula when he did not land properly.

“A lot of skateboarding is knowing what to do when we don’t pull off that trick,” Shafer said. “How do we get out of that?”

Referring to Morant, Shafer added: “He has to do that every single time he makes a basket. How am I going to get out of this jam after I accomplish my goal?”

Morant, so far, has been lucky while ascendant and vulnerable.

“I just worry about finishing the play,” he said.

Morant missed two dozen games with knee injuries but returned for the final game of the regular season, allowing for the frequent takeoffs that even those who spend much of their time in the air can only fantasize about.

“I would love to be able to just hang in the air for an extra second or two without any apparatus like he can,” Smith said. “The way he moves, it makes me think of being in a dream and moving in ways that we can’t in real life.”