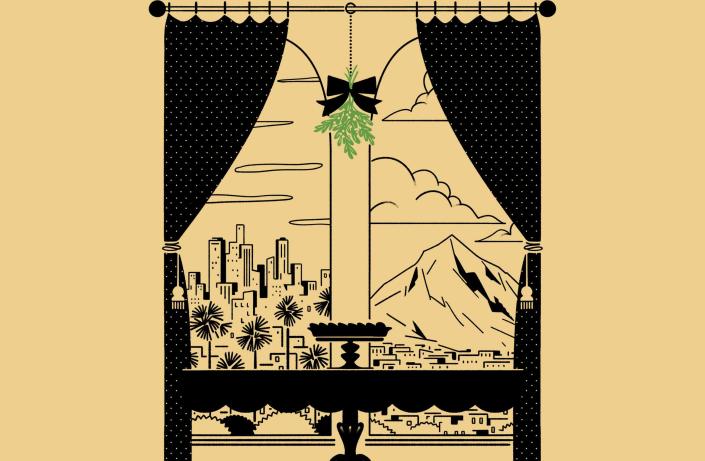

After moving to Southern California to escape the war in Iran in the 1980’s, Liana Aghajanian’s family embraced traditions both old and new during the holiday season.

Simone Massoni

” data-src=”https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Ksez4FjMi4QgzJKpXiXEHA–/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTcwNTtoPTQ2MQ–/https://media.zenfs.com/en/food_wine_804/f1802a2423a802aa48a88f79808303cc”><img alt="

Simone Massoni

” src=”https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/Ksez4FjMi4QgzJKpXiXEHA–/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTcwNTtoPTQ2MQ–/https://media.zenfs.com/en/food_wine_804/f1802a2423a802aa48a88f79808303cc” class=”caas-img”>

Simone Massoni

I always celebrate Christmas twice. Like many people who partake in the holiday on December 25, I attempt, but fail, at the great American pastime of decorating a gingerbread house, eat far too much turkey, and emotionally spiral during the annual viewing of Home Alone. As a child, I remember the conversations of my extended family reverberating through every room, growing increasingly louder as the night wore on, as piles of scrunched-up wrapping paper and dirty dishes dotted the premises.

This was our fun, lighthearted “American Christmas.” It was weightless and untethered, like a party with occasional dancing if someone played the right song. It was the Christmas that we incorporated into our routines over the years as we tried to shake our refugee identities and rebuild our lives in a new country. If it wasn’t perfect, it didn’t matter. Because about 10 days later, we were lucky enough to do it all over again.

Things were a little different on January 6, however. This was the night we celebrated Armenian Christmas. Solemn and serious, it was a quiet evening filled with rituals that tied us to our history, returning us to foundations that went back millennia, foundations we were forced to leave behind, and foundations that we really didn’t have in America.

My earliest years were marked by the Iran-Iraq War. Born in Iran to parents of Armenian descent, I spent time on and off in the basement of our house in Tehran as bomb sirens went off around us in response to the air raids and missile attacks raining down on the capital in the late ’80s. Like many Armenian and Iranian families at the time, we left when we could and eventually ended up thousands of miles away, in Southern California.

I was too young to fully remember what had come before our lives in Los Angeles. But growing up in America meant that I always had a Christmas do-over; a second chance tying me to another time and place that I looked forward to every year.

January 6 is when the table transcended to another world. Pieces of unleavened bread — blessed at the local Armenian church and brought home in wax paper envelopes — were placed at the bottom of cups filled with wine and drunk after prayers. Salty fish was paired with steaming white rice and aromatic herbs. Yogurt soup made with barley overflowed our bowls. And then there was Anoush Abour (the translation is literally “sweet soup” in English, it’s known as “Noah’s pudding”), an ancient dish that signals prosperity and good fortune with a legacy spanning back to biblical times.

It was a quiet evening filled with rituals that tied us to our history, returning us to foundations that went back millennia.

The story goes that Noah and his family and all the animals he crammed into the ark were running out of food while it continued to rain for 40 days and 40 nights. So Noah began boiling a big pot of water and asked everyone to bring what was left. In went wheat and dried fruit, as the passengers of the ark looked on. As the mixture boiled, the rain stopped. Noah and his ark came to land on the “mountains of Ararat,” according to the Book of Genesis, and the dish came to symbolize the first meal that was eaten after they found refuge.

Once indigenous inhabitants of the areas around Ararat, Armenians revere the mountain to this day, and since ours was the first country to adopt Christianity in the fourth century, the tale of Noah and his ark remains just as special.

As I get older, this annual, laborious preparation of Noah’s pudding, a warm and nourishing pot of wheat, raisins, dried apricot, and almonds topped off by intricate designs using pomegranate seeds, makes me think of another kind of do-over on my second Christmas.

What would my life look like if a series of circumstances had never brought me to America? Where would I be celebrating? What if I could go back beyond Tehran, the place of my birth, and have a do-over of modern Armenian history — a history with waves of violence and displacement strong enough that their ripple effects continue to impact us today?

A genocide that culminated in 1915, where over one million Armenians were systematically killed and hundreds of thousands of others displaced by the Ottoman government, is the crux that our ancient existence has come to rest on in the modern era. This forced upheaval changed the course of Armenian identity forever, scattering survivors across the world, while permanently severing them from the lands they had inhabited for millennia. There was no going back home; there was only exile. With names of cities changed, their property and land confiscated, and cultural contributions obscured, home as they knew it ceased to exist.

Who would I be if I — and millions of others — could access these same physical spaces we have been denied, the place where our ancestors lived, ate, and died, instead of finding ourselves thousands of miles away?

I would trade the privilege of two Christmases for just one, if only to feel the weight of that ground under my feet. This is a sense of security not granted to peoples whose national and sometimes individual struggle for survival feel as permanent as a shadow.

It’s an impossible do-over, a nostalgic daydream. But Noah’s pudding is real, and so is my second Christmas. It’s a portal that I create every year, one that connects me to a tangible inheritance made with my hands. It’s a chance to cement connections to foundations that can’t be broken, no matter how far away they might be — so long as I never forget. So long as I keep stirring the pot.

Anoush Abour (Noah’s Pudding)

Victor Protasio / Food Styling by Margaret Monroe Dickey / Prop Styling by Jillian Knox

” data-src=”https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/AU9Od6R_HAmA.UYekXvS5A–/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTcwNTtoPTcwNQ–/https://media.zenfs.com/en/food_wine_804/74671405585b06229a3991001c61d8d3″><img alt="

Victor Protasio / Food Styling by Margaret Monroe Dickey / Prop Styling by Jillian Knox

” src=”https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/AU9Od6R_HAmA.UYekXvS5A–/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTcwNTtoPTcwNQ–/https://media.zenfs.com/en/food_wine_804/74671405585b06229a3991001c61d8d3″ class=”caas-img”>

Victor Protasio / Food Styling by Margaret Monroe Dickey / Prop Styling by Jillian Knox

This popular Armenian Christmas and New Year’s dish is a softened wheat berry porridge topped with dried fruits and nuts.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Born in Tehran, raised in Los Angeles, and currently living in Detroit, Liana Aghajanian is a journalist specializing in narrative storytelling and international reporting. Her archival project, Dining in Diaspora, explores the intersection of cuisine and forced migration and identity within the Armenian community in America. She is a winner of the Write A House residency for Detroit-based writers.