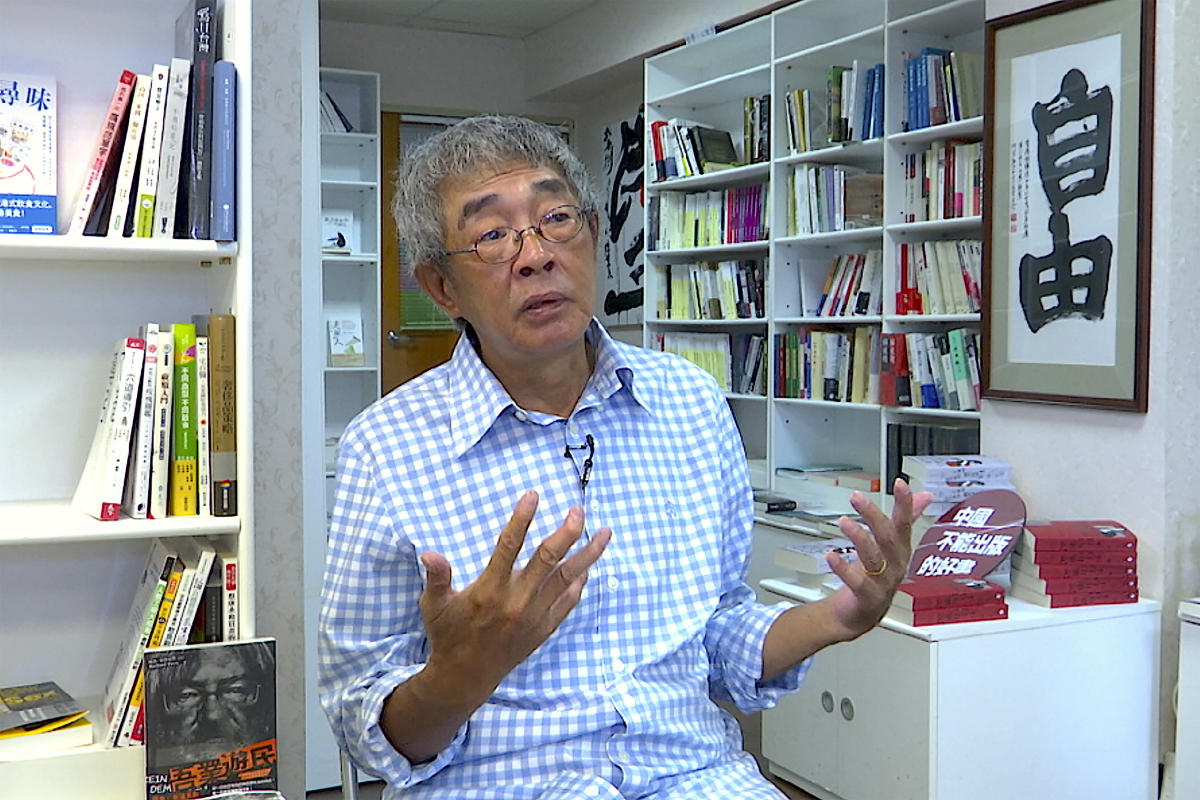

TAIPEI, Taiwan (AP) — For Lam Wing-kee, a Hong Kong bookstore owner who was detained by police in China for five months for selling sensitive books about the Communist Party, coming to Taiwan was a logical step.

An island just 640 kilometers (400 miles) from Hong Kong, Taiwan is close not just geographically but also linguistically and culturally. It offered the freedoms that many Hong Kongers were used to and saw disappearing in their hometown.

Lam’s move to Taiwan in 2019, where he reopened his bookstore in Taipei, the capital, presaged a wave of emigration from Hong Kong as the former British colony came under the tighter grip of China’ s central government and its long-ruling Communist Party.

“It’s not that Hong Kong doesn’t have any democracy, it doesn’t even have any freedom,” Lam said in a recent interview. “When the English were ruling Hong Kong, they didn’t give us true democracy or the power to vote, but the British gave Hong Kongers a very large space to be free.”

Hong Kong and Chinese leaders will mark next week the 25th anniversary of its return to China. At the time, some people were willing to give China a chance. China had promised to rule the city within the “one country, two systems” framework for 50 years. That meant Hong Kong would retain its own legal and political system and freedom of speech that does not exist in mainland China.

But in the ensuing decades, a growing tension between the city’s Western-style liberal values and mainland China’s authoritarian political system culminated in explosive pro-democracy protests in 2019. In the aftermath, China imposed a national security law that has left activists and others living in fear of arrest for speaking out.

Hong Kong still looked the same. The malls were open, the skyscrapers were gleaming. But well-known artist Kacey Wong, who moved to Taiwan last year, said he constantly worried about his own arrest or those of his friends, some of whom are now in jail.

“On the outside it’s still beautiful, the sunset at the harbor view. But it’s an illusion that makes you think you’re still free,” he said. “In reality you’re not, the government is watching you and secretly following you.”

Though Wong feels safe in Taiwan, life as an exile is not easy. Despite its similarities to Hong Kong, Wong found his new home an alien place. He does not speak Taiwanese, a widely spoken Fujianese dialect. And the laid-back island contrasts strongly with the fast-paced financial capital that was Hong Kong.

The first six months were hard, Wong said, noting that traveling as a tourist to Taiwan is completely different than living on the island in self-imposed exile.

“I haven’t established the relationship with the place, with the streets, with the people, with the language, with the shop downstairs,” he said.

Other, less prominent exiles than Wong or Lam have also had to navigate a system that does not have established laws or mechanisms for refugees and asylum seekers, and has not always been welcoming. That issue is further complicated by Taiwan’s increasing wariness of security risks posed by China, which claims the island as its renegade province, and of Beijing’s growing influence in Hong Kong.

For example, some individuals such as public school teachers and doctors have been denied permanent residency in Taiwan because they had worked for the Hong Kong government, said Sky Fung, the secretary general of Hong Kong Outlanders, a group that advocates for Hong Kongers in Taiwan. Others struggle with the tighter requirements and slow processing of investment visas.

In the past year or so, some have chosen to leave Taiwan, citing a clearer immigration path in the U.K. and Canada, despite the bigger gulf in language and culture.

Wong said that Taiwan has missed a golden opportunity to keep talented people from Hong Kong. “The policies and actions, and what the … government is doing is not proactive enough and caused uncertainty in these people, that’s why they’re leaving,” he said.

The island’s Mainland Affairs Council has defended its record, saying it found that some migrants from Hong Kong hired immigration companies who took illegal methods, such as not carrying through on investments and hiring locals they had promised on paper.

“We in Taiwan, also have national security needs,” Chiu Chui-cheng, deputy minister at the Mainland Affairs Council, said on a TV program last week. “Of course we also want to help Hong Kong, we have always supported Hong Kongers in their support for freedom, democracy and rule of law.”

Some 11,000 Hong Kongers got residence permits in Taiwan last year, according to Taiwan’s National Immigration Agency, and 1,600 were able to get permanent residency. The U.K. granted 97,000 applications to Hong Kong holders of British National Overseas passports last year in response to China’s crackdown.

However imperfect, Taiwan gives the activists a chance to continue to carry out their work, even if the direct actions of the past were no longer possible.

Lam was one of five Hong Kong booksellers whose seizure by Chinese security agents in 2016 drew global concern.

He often lends his presence to protests against China, most recently attending a June 4 memorial in Taipei to mark the anniversary of a bloody crackdown on democracy protesters in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989. Similar protests in Hong Kong and Macao, until recently the only places in China allowed to commemorate the Tiananmen massacre, are no longer allowed.

“As a Hong Konger, I actually haven’t stopped my resistance. I have always continued to do what I needed to do in Taiwan, and participated in my events. I have not given up fighting,” Lam said.