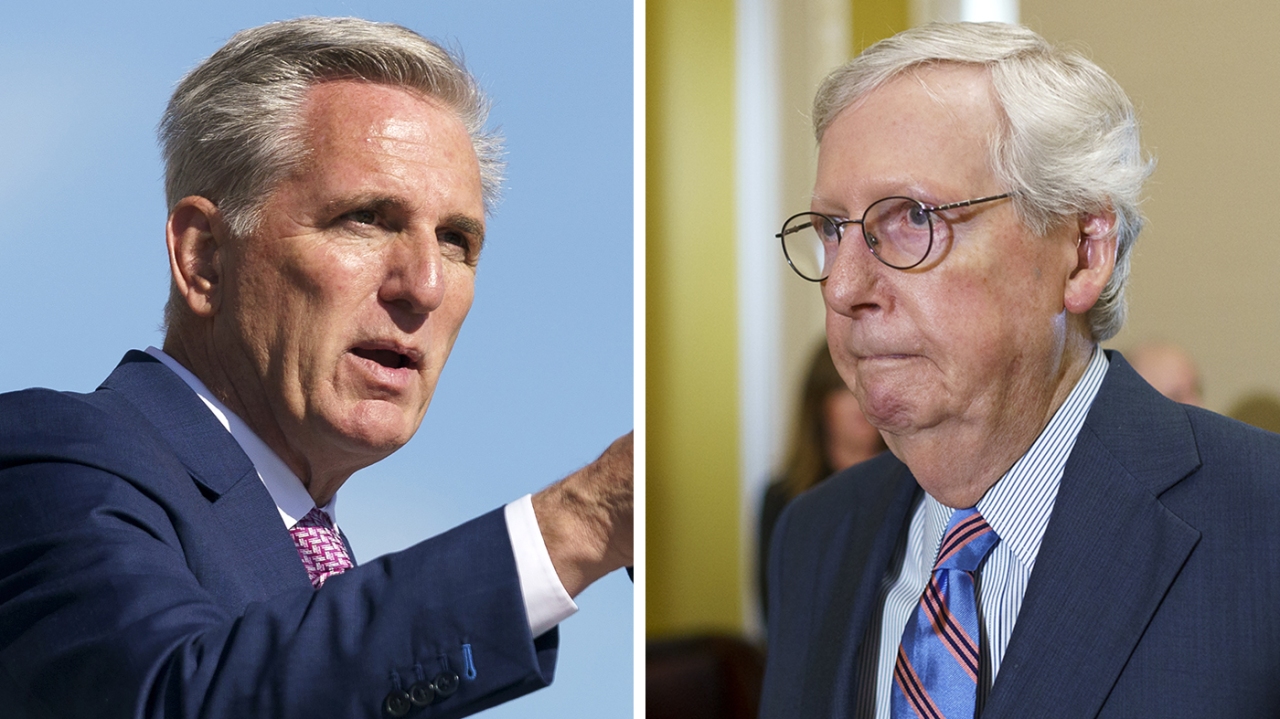

Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell (Ky.) and House GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy (Calif.) are headed for a collision next year on spending more money to help Ukraine.

McConnell has led Republican support for sending generous military and financial aid to Kyiv, warning that Russian President Vladimir Putin could threaten Poland and other European allies if not stopped in Ukraine.

McCarthy, who would likely become Speaker if Republicans win control of the House, is putting the brakes on more Ukraine aid, warning this week there won’t be a “blank check” from a GOP majority.

McConnell took an unannounced trip to Ukraine in May to meet with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. He said he hoped “not many members of my party will choose to politicize this issue,” also highlighting that House Republicans voted for a $40 billion Ukraine package that month.

But House Republican support for the war in Ukraine is eroding as the conflict drags on, and experts predict the United States could be headed into a recession next year, which could diminish support for sending tens of billions of dollars in additional aid to Ukraine.

It’s the first significant policy difference between McCarthy and McConnell that will come into the spotlight after Election Day. Congress will reconvene next month to wrap up the unfinished business of the 117th Congress.

Congress last month approved $12.3 billion in military and economic aid for Ukraine as part of a stopgap spending measure. McConnell voted for it and McCarthy voted “no,” as did the vast majority of the House Republican Conference.

Senate aides say they expect the year-end omnibus spending package to include more money for Ukraine and speculate that President Biden may ask for a large amount for Ukraine to cover what may be months of legislative gridlock in the House next year.

McCarthy will still be in the minority in the lame-duck session, but he will have much more leverage over spending bills if he becomes Speaker. He may refuse to put bills on the House floor next year that don’t have support from a majority of his conference.

“I would imagine that there would be significant tension because McConnell certainly is not going to shy away from continuing to support Ukraine,” said a Senate Republican aide.

“One way to solve this is to put a huge slug of money in [the omnibus spending package] in December,” the aide added.

But the GOP source said that McConnell and McCarthy could work out a deal next year on Ukraine money by demanding that Democrats agree to more oversight on military and economic aid to Kyiv.

Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) held up a Ukraine assistance bill earlier this year in an attempt to add language setting up a special inspector general to monitor the spending. That idea could get more traction if Republicans control the House.

The tension between the GOP leaders also points to a wider split. While a number of prominent Republicans, including Rep. Liz Cheney (Wyo.) and former Vice President Mike Pence, have pushed back on McCarthy’s skepticism, his comments echoed concerns voiced by former President Trump and his allies in the House.

In an interview published Tuesday, McCarthy told Punchbowl News: “I think people are gonna be sitting in a recession and they’re not going to write a blank check to Ukraine.”

His statement caused an immediate uproar among some national security–minded Republicans, with Cheney blasting the idea that House conservatives would hold up more aid to Ukraine as “disgraceful.”

“I don’t know that I can say I was surprised, but I think it’s really disgraceful that Minority Leader McCarthy suggested that if the Republicans get the majority back that we will not continue to provide support to Ukrainians,” she said at an event hosted by the Harvard Institute of Politics.

Pence also pushed back against House Republican opposition to future Ukraine aid bills, telling an audience at the Heritage Foundation: “We must continue to provide Ukraine with the resources to defend themselves.”

McConnell stayed silent on the subject Wednesday, taking a cautious approach less than three weeks before Election Day, when he will need Republicans voters across the ideological spectrum to turn out.

Ford O’Connell, a Republican strategist, said McCarthy is more aligned than McConnell with Trump’s “America First” brand of foreign policy.

“McCarthy is saying exactly what the Republican base is saying when it comes to Ukraine and the threat of China,” he said, noting that some conservative Republicans say that money spent on Ukraine detracts attention from China, which they see as a bigger threat.

“We’re not saying ‘Don’t support Ukraine,’ but we are saying, ‘You can’t be having blank checks, billions of dollars going down the hole, weapons you can’t trace, all the while you have a big problem with China,’” O’Connell said.

He added, “McConnell’s position reflects more the traditional Republican position of [the United States] acting as the global police.”

If Republicans win the House majority, McCarthy could also demand a freeze on spending until they take control of the chamber next year.

Michael E. O’Hanlon, a senior fellow and director of research in foreign policy at Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank, said “it will be fascinating to watch” the debate over Ukraine assistance play out among Republicans.

He warned that McCarthy needs to be careful so that he doesn’t come across as inadvertently helping Putin.

“I have a hard time believing that deep down, McCarthy and most Trump Republicans really will want to be seen as the folks that prevent Ukraine from staying afloat as a country,” he wrote in an email to The Hill. “The political perils of actually helping Putin win would be enormous — to say nothing of the ethical downsides.”

McCarthy softened his stance on Wednesday, telling CNBC in an interview: “I think Ukraine is very important.”

“I support making sure that we move forward to defeat Russia in that program. But there should be no blank check on anything. We are $31 trillion in debt.”

Conn Carroll, a former Senate aide who advised conservative Republicans in Congress, said U.S. interests don’t completely overlap with Ukrainian interests and there should be more oversight.

“U.S.-Ukraine relations overlap a lot, but at some point they begin to diverge,” he said, pointing to recent reporting that U.S. intelligence officials believe the Ukrainian government authorized the assassination of Russian citizen Daria Dugina, the daughter of a prominent Russian nationalist.

“We do need to know how this money is being spent and make sure it’s not supporting assassination attempts, which are not conducive to American national security interests,” said Carroll, who is now the commentary editor at the Washington Examiner.

O’Hanlon, of Brookings, said House Republicans will put up a fight against more spending for Ukraine if they win back the majority but are likely to agree at some point next year to more assistance.

“I do expect the process to get uglier and more contentious if the Republicans win back the House,” he said. “But I really don’t expect the results to be radically different, once the smoke clears and the appropriations bills are written.”