ALEXANDRIA, Va. — A teacher from Kansas who had converted to Islam traveled to the most dangerous conflicts in the world — Libya, Iraq, Syria — hoping to wage war.

Syria was where the teacher, Allison Fluke-Ekren, ultimately made her mark: She rose through the ranks of the Islamic State, commanding a battalion of female fighters and training more than 100 women and girls, including her own daughter.

Even as her daughter eventually escaped to Kansas in 2017, Ms. Fluke-Ekren stayed, hoping to die defending the so-called caliphate and trying to trick her family in the United States into believing she was no longer alive. She was finally detained in the summer of 2021, held by unknown forces in Syria, before being brought to the Eastern District of Virginia in January on a charge of providing material support to terrorists.

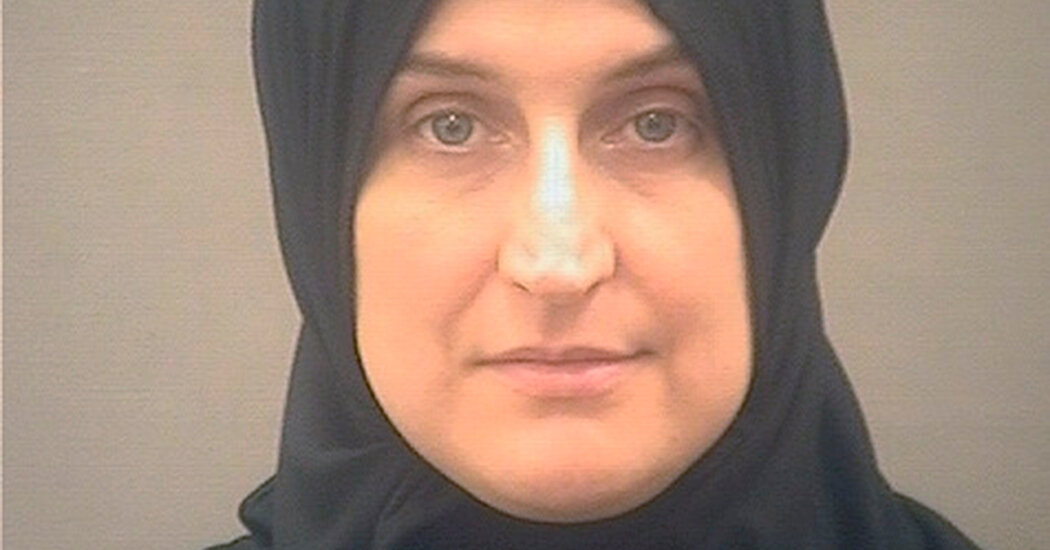

On Tuesday, Ms. Fluke-Ekren, 42, pleaded guilty to the single charge in a federal courtroom in Northern Virginia. As part of a plea deal, Ms. Fluke-Ekren detailed her role in Syria as well as a previously undisclosed connection to the 2012 attacks in Benghazi that killed four Americans, including the U.S. ambassador to Libya.

For the F.B.I. and prosecutors, her conviction marked the end of a seven-year hunt. Ms. Fluke-Ekren’s hardened militancy and unusually high-level position in the Islamic State stand out even among the Americans who traveled to wage jihad in Syria. The case was the first prosecution in the United States involving a top female military leader of the Islamic State, the first assistant U.S. attorney, Raj Parekh, said during the hearing on Tuesday.

A teenage mother from Overbrook, Kan., Ms. Fluke-Ekren slowly embraced the Islamic State’s ideology and had a knack for languages, according to Amy Farouk, a former friend.

“It was a way for her to feel important,” Ms. Farouk said. “It made her have a sense of purpose.”

Efforts to reach Ms. Fluke-Ekren’s family in Kansas were unsuccessful. But Ms. Farouk, who said she met Ms. Fluke-Ekren in about 2001, filled out portions of her life. At the time, Ms. Fluke-Ekren was a teacher at the Islamic School of Greater Kansas City.

After Ms. Fluke-Ekren had two children and her first marriage in Kansas fell apart, she met an international student from Turkey, Volkan Ekren, at the University of Kansas, where both majored in the sciences, Ms. Farouk said. Ms. Fluke-Ekren graduated in 2007 and then attended a teaching program at Earlham College in Indiana, prosecutors said.

The two eventually married and had five children together, all of whom were born in the United States.

In about 2008, Ms. Fluke-Ekren and Mr. Ekren moved to Cairo, where they lived in the upscale Sheikh Zayed City, according to Ms. Farouk, who relocated there around the same time. “Life was good,” Ms. Farouk recalled, noting that her friend spoke Arabic fluently.

The family moved to Libya in late 2011, Ms. Farouk said. According to the plea agreement, Ms. Fluke-Ekren and her husband lived in Benghazi at the time of the 2012 attacks on an American diplomatic compound and a nearby C.I.A. base. In the aftermath of the attacks, prosecutors said Mr. Ekren claimed to have removed a box of documents and at least one electronic device from the U.S. compound and taken them home.

Ms. Fluke-Ekren admitted to helping him sort through the documents and prepare summaries that were provided to the leaders of Ansar al-Shariah, a terrorist organization accused of leading the attack on the American diplomatic mission in Benghazi. In late 2012, the family left Libya because Ansar al-Shariah was no longer conducting attacks in the country, according to the statement of facts.

Shortly after, the couple traveled to Syria, but Ms. Fluke-Ekren returned to Turkey while Mr. Ekren stayed and later oversaw Islamic State snipers. She joined him in Syria in 2014, but the next year, they moved to Mosul, Iraq, where she helped ISIS in handling widows whose husbands had died fighting.

The family returned to Syria, and Mr. Ekren was killed in an airstrike as he was conducting reconnaissance for a terrorist attack, prosecutors said.

Prosecutors said Ms. Fluke-Ekren married another Islamic State terrorist, a Bangladeshi man who specialized in drones and worked on a plan to drop chemical bombs using them. After the man, Wamiq al-Bengali, died, Ms. Fluke-Ekren married another Bangladeshi man, an Islamic State military leader who was responsible for defending Raqqa, Syria. He died while fighting for ISIS in 2018.

Ms. Fluke-Ekren admitted that she wanted to launch attacks in the United States, including on a college that prosecutors did not identify. According to the criminal complaint, her plan was presented to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, then the leader of the Islamic State, who approved funding it. Mr. al-Baghdadi was killed in a raid in 2019 by American commandos.

The complaint said Ms. Fluke-Ekren ran the battalion in 2016, training children on how to use AK-47 assault rifles, grenades and suicide belts. One witness saw one of Ms. Fluke-Ekren’s children, who was about five or six years old at the time, holding a machine gun at her home in Syria.

She was smuggled out of Syria in about May 2019 and married a fifth time, according to the statement of facts. But the couple separated, and Ms. Fluke-Ekren tried to surrender to the local police near Qabasin, Syria. Two weeks later, she was taken to a detention facility in Jarabulus, Syria. It is not clear who ran the prison.

Mr. Parekh said that Ms. Fluke-Ekren had left a “trail of betrayal” and that her family members might want to make victim statements when she is sentenced in October. She faces up to 20 years in prison.

When Judge Leonie M. Brinkema mentioned her children, Ms. Fluke-Ekren became visibly upset and began to weep.

Ms. Fluke-Ekren has at least seven children, including five with Mr. Ekren. Federal authorities brought back six of them to the United States, people familiar with the matter said. At least one child, a son she had with her second husband, was killed in an airstrike in Syria. Her oldest son, who had lived with her in Cairo, returned to Kansas before Ms. Fluke-Ekren went to Libya.

Ms. Fluke-Ekren’s case is part of an aggressive effort by federal prosecutors in Virginia to prosecute terrorists captured abroad.

Mohammed Khalifa, a Saudi-born Canadian who traveled to Syria in 2013 and later joined the Islamic State, was brought to the United States last year and charged with providing material support to a terrorist organization that resulted in death. He later pleaded guilty and faces life in prison.

Two British men, El Shafee Elsheikh and Alexanda Kotey, who were part of a notorious ISIS cell of Britons called “the Beatles,” were eventually captured and prosecuted. The group kidnapped and tortured more than two dozen hostages, including the American journalists James Foley and Steven J. Sotloff, both of whom were beheaded in propaganda videos.

Mr. Kotey pleaded guilty to his role in the deaths of four Americans in Syria and was sentenced to life in prison. In April, a jury convicted Mr. Elsheikh, who also faces a mandatory sentence of life in prison for his part in the brutal kidnapping scheme.