HONG KONG — On his first full day on the job, Hong Kong’s new leader, John Lee, shared a picture of himself working at his desk with a printout of what he described as an important speech by Xi Jinping, China’s leader, placed next to his notebook.

Mr. Lee is not the only Hong Kong official hanging on Mr. Xi’s words. Lawmakers held a six-hour session this month lauding Mr. Xi’s remarks on Hong Kong, with several also praising him for visiting the city recently despite an approaching typhoon and a Covid outbreak. And hundreds of top officials have attended group study sessions, including one titled “Spirit of the President’s Important Speech” held by the Civil Service Bureau. In a government news release describing the session, the term “important speech” was used 10 times, in nearly every paragraph.

In mainland China, such displays of devotion to the country’s powerful leader are common, particularly under Mr. Xi, who moved early in his tenure to revive strongman politics and a cult of personality around him. But they represent a jarring shift for Hong Kong, a former British colony that was granted a high degree of autonomy when it returned to Chinese control 25 years ago.

While Hong Kong has long had to abide by Beijing’s decisions over major issues, the bureaucracy’s conspicuous embrace of Mr. Xi has crystallized the city’s new identity as a territory firmly in Beijing’s grip. The performance of loyalty to Mr. Xi is the latest feature of the Communist Party’s assertive approach to Hong Kong and its efforts to tame the city’s defiant political streak.

“In the history of Hong Kong, this is an unusual reaction,” said John P. Burns, an emeritus professor at the University of Hong Kong. “We have never spent so much time and energy poring over a speech.”

In his speech, made on July 1 in Hong Kong to mark the 25th anniversary of the territory’s return to Chinese control, Mr. Xi emphasized that “political power must be in the hands of patriots.” His remarks were printed by state-owned publishing houses and displayed in bookshops alongside other books by the Chinese leader about governance, which have also been recently released in traditional Chinese characters for the Hong Kong market.

So far Mr. Xi’s writings have received a mixed reaction from the public, with many people treating them as a curiosity. But among the pro-Beijing camp that now dominates Hong Kong politics, studying Mr. Xi, and being seen doing it, has become increasingly essential.

Mr. Lee, Hong Kong’s chief executive, a longtime security official who was handpicked by Beijing, has led the campaign to study Mr. Xi’s words, giving talks at sessions for top officials. He called Mr. Xi’s Hong Kong speech a “blueprint” for the city and said he was organizing his government to meet its demands.

He has cited Mr. Xi’s comments at most of his public events this month, including an exhibition of a giant hanging lantern and the graduation of a new class of police recruits. Mr. Lee encouraged the incoming officers to heed Mr. Xi’s reminder that “Hong Kong cannot withstand chaos.” (To mark their graduation, the new recruits goose-stepped in a parade, the first time the step has been used in the ceremony after Hong Kong law enforcement bodies dropped the British-style march.)

The frequent references to the Chinese leader mark not just Beijing’s heavier hand in the governance of Hong Kong, but also the weakness of a local government that has been battered by mass protests and then the pandemic. Mr. Lee, who spent nearly his entire career with the police and the security service, lacks the sort of broad network his predecessors brought to the job through lengthy experience in the civil service or in business.

“The leader of this government is much more dependent on the central government than any previous government,” Mr. Burns, of the University of Hong Kong, said.

Mr. Xi’s brief visit to Hong Kong, his first in five years, was a victory lap for the leader as he declared an end to the city’s recent era of large-scale dissent. He urged the government to address livelihood issues like a lack of access to housing and economic opportunity, the sort of issues that Beijing’s allies have said are the root of Hong Kong’s mass pro-democracy protests.

Mr. Xi also issued orders for Hong Kong when he visited in 2017, warning that any challenge to Beijing’s authority “crosses the red line.” But those words were largely ignored until 2020, when Beijing imposed a tough security law on the city, part of a sweeping crackdown that left most of the city’s prominent pro-democracy politicians in prison or exiled. The legislative council once saw boisterous debates and occasional heated protests, but such divisions vanished after Beijing implemented new rules to ensure only “patriots” could run for office.

After Mr. Xi’s visit this month, dozens of lawmakers spent six hours praising Mr. Xi’s speech and the support he showed for Hong Kong during his trip. “President Xi, fearless of the epidemic risk and the typhoon threat, made an important speech in Hong Kong,” Regina Ip, a veteran pro-Beijing lawmaker, said.

Ted Hui, a former opposition lawmaker who went into exile, said he was shocked by the discussion of Mr. Xi.

“In the past, Hong Kong politics and the politics of mainland China were quite separate under the ‘one country, two systems’ practice, and in Hong Kong’s legislative council we didn’t talk about the speeches of mainland politicians,” he said.

“What I see is that the culture of the mainland political system has been brought into Hong Kong,” he added. “It is a personality cult.”

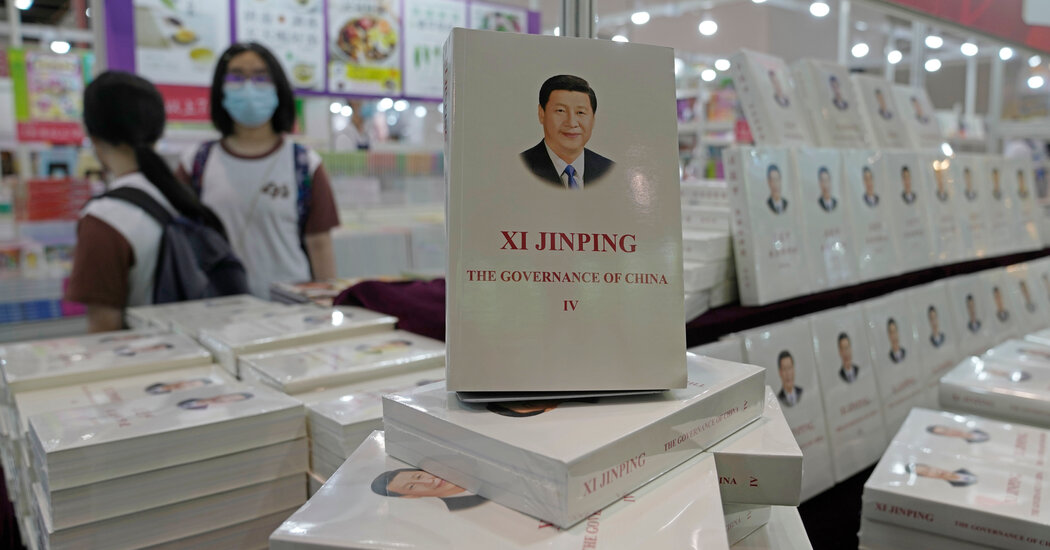

At the Hong Kong Book Fair this week, newly printed copies of Mr. Xi’s Hong Kong speech and works such as “Xi Jinping: The Governance of China IV,” the latest installment of his speeches and writings, were displayed prominently at the entrance to the vast display hall.

The presence of Mr. Xi’s work at the fair was covered breathlessly by state media, with a China Daily headline calling Mr. Xi’s books a “big hit.” Top Hong Kong officials made highly publicized visits to the fair to buy copies of the books.

But on Monday, more people were taking photos of the stacks of books than reading or buying them.

Many visitors said his name out loud upon spotting the books. One man sporting a basketball jersey and tattoo sleeve paged through one tome with studied erudition as he posed for photos, suppressing his laughter.

Chung Wah Chow, a freelance writer, said she came in search of “red books” after seeing social media posts about them. She spent several minutes comparing the English version of a compilation of the Chinese leader’s speeches and written work to the original Chinese. She said that the translation was better than she had expected.

After putting the book back, she lingered, watching to see if others would approach the booth. Few did.

“No one is lining up here,” she said. “I’m thinking of the workers who will have to carry all these heavy books after the fair.”